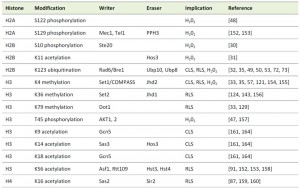

Reviews:

Microbial Cell, Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 1 - 13; doi: 10.15698/mic2016.01.472

Histone modifications as regulators of life and death in Saccharomyces cerevisiae

Institute of Molecular Biology and Medicine, Université Libre de Bruxelles, Rue Profs. Jeener et Brachet 12; 6041 Charleroi, Belgium.

Keywords: apoptosis, autophagy, epigenetics, histone modification, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, yeast.

Abbreviations:

CLS - chronological lifespan,

DSBs - DNA double strand breaks,

HAT - histone acetyltransferase,

HDAC - histone deacetylase,

RLS - replicative lifespan,

ROS - reactive oxygen species.

Received originally: 11/09/2015 Received in revised form: 11/11/2015

Accepted: 27/11/2015

Published: 31/12/2015

Correspondence:

Birthe Fahrenkrog, bfahrenk@ulb.ac.be

Conflict of interest statement: The author declares no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Birthe Fahrenkrog (2015). Histone modifications as regulators of life and death in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbial Cell 3(1): 1-13.

Abstract

Apoptosis or programmed cell death is an integrated, genetically controlled suicide program that not only regulates tissue homeostasis of multicellular organisms, but also the fate of damaged and aged cells of lower eukaryotes, such as the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Recent years have revealed key apoptosis regulatory proteins in yeast that play similar roles in mammalian cells. Apoptosis is a process largely defined by characteristic structural rearrangements in the dying cell that include chromatin condensation and DNA fragmentation. The mechanism by which chromosomes restructure during apoptosis is still poorly understood, but it is becoming increasingly clear that altered epigenetic histone modifications are fundamental parameters that influence the chromatin state and the nuclear rearrangements within apoptotic cells. The present review will highlight recent work on the epigenetic regulation of programmed cell death in budding yeast.

INTRODUCTION

Apoptosis or “programmed cell death” is a self-destructing process important for the development and homeostasis of multicellular organisms and its deregulation contributes to the pathogenesis of multiple diseases including autoimmune, neoplastic and neurodegenerative disorders [1]. Apoptosis is characterized by biochemical and morphological rearrangements throughout the cell [2] with chromatin condensation conjoint by DNA fragmentation being one of the most important nuclear alterations [3]. The mechanism by which chromosomes reorganize during apoptosis is still poorly understood, but recent years have shown that epigenetic changes of the chromatin state are fundamental parameters of the nuclear rearrangements experienced by apoptotic cells.

–

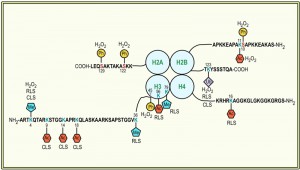

Chromatin is a composite of packaged DNA and associated proteins, in particular histones [4]. The basic subunit of chromatin is the nucleosome containing 147 base pairs of DNA, which are wrapped around a histone octamer containing two copies each of the core histones H2A, H2B, H3 and H4. Nucleosomes are then packaged into higher order structures in a yet controversially discussed manner [5], in which individual nucleosomes are separated from each other by the linker histone H1 and its isoforms. The tails of the core histones pass through channels within the DNA molecule away from it and are subjected to a wide variety of post-translational modifications. These post-translational modifications include lysine acetylation, butyrylation, propionylation, ubiquitination and sumoylation, lysine and arginine methylation, arginine citrullination, serine, threonine and tyrosine phosphorylation, proline isomerization as well as ADP ribosylation [6][7][8][9][10]. In the context of apoptosis in particular phosphorylation and acetylation of histones have long been suggested to affect chromatin function and structure during cell death [11].

–

The budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae has matured as attractive model system for apoptotic research to study the evolutionary conserved aspects of programmed cell death. Apoptosis in S. cerevisiae can be activated by various agents including hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), acetic acid and pheromone or by physiological triggers, such as DNA replication stress, defects in DNA damage repair, chronological or replicative aging and failed mating [12][13][14][15][16]. The chronological lifespan (CLS) is defined as the time yeast cells remain alive in a post-mitotic, quiescence-like state [17][18][19] and genetically, amongst others, strongly influenced by key apoptotic regulators, such as Aif1, Bir1, Nma111, Nuc1, Ybh3 and Yca1 [20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28], all of which have homologs in mammals. Replicative aging, the second type of aging studied in yeast, is defined by the number of cell divisions an individual mother cell can undergo before entering senescence (replicative lifespan, RLS) and is equally controlled by some of these genetic factors as well as by environmental conditions [17][19]. Chronological and replicative aging both lead to an accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that ultimately results in programmed death of the budding yeast cells [24][29].

–

As in higher eukaryotes, it is becoming more and more evident that the programmed death of S. cerevisiae is largely influenced by epigenetic modifications, in particular phosphorylation of H2B and H3, acetylation of H3 and H4, deubiquitination of H2B, as well as methylation of H3 [30][31][32][33][34][35]. This review will highlight current knowledge on the posttranslational histone modifications that decide on yeast life and death.

EPIGENETIC REGULATION OF YEAST LIFE AND DEATH

Histone phosphorylation

In metazoans, the first histone modification that had been linked to apoptosis was phosphorylation of the histone variant H2A.X at serine 139 (S139), known as γ-H2AX, that occurs during the formation of DNA double strand breaks (DSBs) under various conditions, including apoptosis [36]. Furthermore, phosphorylation of histone H2B at S14 had been associated with chromatin condensation and DNA fragmentation [37][38][39]. H2B phosphorylation is reciprocal and deacetylation of H2B at lysine 15 (K15) is necessary to allow H2BS14 phosphorylation [40].

–

This unidirectional crosstalk between two histone modifications was originally revealed in yeast: phosphorylation of S10 of H2B (H2BS10ph; Fig. 1) is essential for the induction of an apoptotic-like cell death in H2O2-treated cells [30]. H2BS10A point mutants exhibit increased cell survival accompanied by a loss of DNA fragmentation and chromatin condensation, whereas H2BS10E point mutants display the typical phenotypic markers of apoptosis, including chromatin compaction and DNA fragmentation. Triggering apoptosis by H2O2, acetic acid or the α-factor leads to phosphorylation of H2BS10 and H2BS10ph is preceded by H2A phosphorylation and mediated by the Sterile 20 kinase, Ste20 (Table 1) [30]. It is dependent on the yeast metacaspase Yca1 and the preceding deacetylation of lysine 11 [31].

H2B lysine 11 is acetylated (H2BK11ac) in logarithmically growing yeast [41] and deacetylated upon H2O2 treatment before H2BS10ph occurs. H2BK11ac was found to be present through 60 min of H2O2 treatment and the disappearance of K11ac after 90 min post H2O2-induction coincided with the onset of S10ph in H2B [31]. The crosstalk between H2BS10ph and H2BK11ac is unidirectional and confirmed by H2BK11 mutants: lysine-to-glutamine H2B K11Q mutants, that are acetyl-mimic, are resistant to cell death elicited by H2O2, while lysine-to-arginine H2B K11R mutants that imitate deacetylation promote cell death. Deacetylation of K11 is mediated by the histone deacetylase (HDAC) Hos3 (Table 1)[31].

–

Interestingly, in human cells it has been shown that H2BS14ph, which is mediated by caspase-activated kinase Mst1, is read by RCC1 [42]. RCC1 is chromatin-bound and the guanine nucleotide exchange factor for the RanGTPase, which acts as a molecular switch to regulate directionality of nucleocytoplasmic transport as well as distinct steps of mitosis, such as spindle and nuclear envelope assembly [43][44][45]. H2BS14ph immobilizes RCC1 on chromatin, which causes a reduction of nuclear RanGTP levels and the inactivation of the nucleocytoplasmic transport machinery [42], which in turn contributes to the inactivation of survival pathways, such as NF-κB signaling [11]. Whether H2BS10ph in yeast has a similar effect on the nucleocytoplasmic transport machinery and survival pathways remains to be studied.

–

A potential trans-histone crosstalk related to yeast apoptosis occurs between H2A and H3 phosphorylation: phosphorylation of H2AS129, which resembles γ-H2AX of higher eukaryotes [46], is increasing in yeast cells undergoing H2O2-induced apoptosis and it is paralleled by a decrease in phosphorylation of threonine 45 in histone H3 (H3T45ph) [47]. On the other hand, the function of H3T45ph in apoptotic signalling has been questioned and rather been linked to DNA replication and its absence with replicative defects [11]. Oxidative damage of DNA by menadione, a reactive quinone that as H2O2 generates ROS, has furthermore been shown to lead to phosphorylation of H2A at serine 122 (H2AS122), and serine-to-alanine H2AS122A mutants have impaired survival on plates containing DSB-inducing drugs, such as methyl methanesulfonate (MMS) or bleomycin [48], supporting the potential importance of H2A phosphorylation in apoptotic signalling during DNA damage response. However, further investigations are necessary to provide mechanistic insights.

–

Histone H2B ubiquitination

Another apoptosis-related modification of H2B is its ubiquitination (Fig. 1). H2B is monoubiquitinated (H2Bub1) at K123, which, in S. cerevisiae, is mediated by the macromolecular complex containing the E2-conjugating enzyme Rad6 and the E3 ligase Bre1 (Table 1) [49][50][51]. H2Bub1 has been linked to transcriptional activation and elongation and BRE1 disruption or lysine-to-arginine substitution at K123 of H2B (H2B-K123R) results in a complex phenotype that includes failures in gene activation [52][53][54][55] and lack of telomeric silencing [56][57][58][59]. H2Bub1 is important for nucleosome stability [60], it marks exon-intron structure in budding yeast [61] and prevents heterochromatin spreading [62], and it is implicated in DNA repair and checkpoint activation after DNA damage [63][64] and during meiosis [65]. The function of H2Bub1 and Bre1 and its homologues in transcription regulation and DNA damage response appears conserved across evolution [66][67][68][69][70]. In human cells and in Drosophila it was furthermore shown that H2Bub1 is facilitated by O-linked N-acetylglucosamine modification of H2B at S112 [71].

–

The DNA damage response machinery is closely linked to apoptosis in yeast and higher eukaryotes [14]. The observation that a loss of the ubiquitin-specific protease UBP10, which is involved in cleaving the ubiquitin moiety from H2B (Table 1) [72][73], activates the yeast metacaspase Yca1 and apoptosis [74], were first hints that H2B ubiquitination may in fact be involved in the regulation of yeast apoptosis. The finding that enhanced expression of Bre1 protected yeast cells from H2O2-induced cell death, whereas deletion of BRE1 potentiated cell death verified this notion [32].

–

During chronological aging, cells lacking bre1 show shortened lifespan that coincides with the appearance of typical apoptotic markers, such as DNA fragmentation and accumulation of ROS. The ability of Bre1 to reduce cell death is conferred by its E3 ubiquitin ligase activity mediated by its C-terminal zinc-binding RING finger domain [50]. RING domains are frequently found in E3 ubiquitin ligases and required for catalysing the transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to the substrate [75]. ∆bre1 cells complemented with a RING finger mutant of Bre1 (C648G, C651G) lack H2Bub1 and exhibited increased apoptosis sensitivity similar to ∆bre1 cells, whereas the complementation of ∆bre1 cells with a functional Bre1 made the cells behave like wild-type [32]. Furthermore, H2B-K123R mutant cells, which too lack H2Bub1, have an increased sensitivity to apoptotic stimuli, exactly as ∆bre1 cells.

–

Yeast cells deficient for ubp10 display markers of apoptosis, such as DNA fragmentation, as well as enhanced expression of stress-responsive genes as compared to wild type [76]. The increased sensitivity to apoptosis observed in both ∆bre1 and ∆ubp10 strains is associated with an increase in the activity of Yca1, while deletion of yca1 restored the wild-type phenotype [32][74]. Deletion of Silencing Information Regulator 2 (Sir2), a NAD+-dependent HDAC that amongst a plethora of targets predominately removes acetyl groups from K16 of histone H4 (Table 1) [77], could partially rescue the transcriptional pattern and abrogate the apoptotic effects of ∆ubp10 cells, suggesting that increased YCA1 expression may result from inappropriate localization of silencing complexes upon failed deubiquitination of H2B [72][73][76].

–

H2B ubiquitination is also an important regulator of the replicative lifespan of S. cerevisiae: replicatively aged cells have increased H2Bub1 in their telomeric heterochromatin, along with increased methylation of histone H3 at lysine 4 and 79 (H3K4 and H3K79; see section “Histone methylation”), respectively [35][78]. Yeast aging is accompanied by the loss of transcriptional silencing at the three heterochromatic regions of the yeast genome: at least at one telomere [79], at the mating type locus [80] and of rDNA [81]. A key regulator of telomeric heterochromatin and rDNA silencing is Sir2 [82][83][84][85][86], which is furthermore of vital importance for RLS regulation: its over-expression extends lifespan [87], while yeast cells lacking sir2 have a shorter lifespan [88]. The effect on the RLS is likely due to Sir2’s ability to repress rDNA recombination [89], which in turn hampers the formation of extrachromosomal rDNA circles [87]. The protein levels of Sir2 typically decrease during aging, which leads to increased levels of acetylated histone H4 at lysine 16 (Fig. 1) and a concomitant loss of histones from specific subtelomeric regions of the genome [90]. The increase in H2Bub1 in replicatively aged yeast cells coincides with decreased Sir2 abundance and an increase in acetylation of histone H4 at K16 (H4K16ac; see section “Histone acetylation”) along with much lower occupancies of H3, H4, or H2B at the heterochromatic regions [35]. A global loss of histones during aging was previously also observed by Feser et al. [91]. In addition to H2Bub1, also methylation of H3K4 and H3K79 are enriched in aged cells at regions proximal to telomeres [35]. Consequently deficiencies in rad6 and bre1 and the expression of H2B-K123R cells reduce the mean lifespans of yeast cells, which is not further reduced by deletion of sir2. Together these data indicate that H2B monoubiquitination and methylation of H3K4 and K3K79 regulate replicative aging through a Sir2-related pathway [35].

Regulation of apoptosis by H2Bub1 may further exist in multicellular organisms: deletion of Rfp1, the Bre1 homologue in Caenorhabditis elegans, leads to enhanced germ cell apoptosis in the worms [92] and the depletion of Bre1b, one of the two Bre1 isoforms in mice, leads to a strong increase in apoptosis frequency in different mouse cell types [93]. In higher eukaryotic cells, however, ubiquitinated H2A is the most abundant species [94][95][96][97] and might assume some of the roles ubiquitinated H2B plays in yeast. Therefore H2A deubiquitination has been linked to chromatin condensation in mitotic and apoptotic cells in higher eukaryotes and the disappearance of H2Aub1 to late apoptotic events [98]. In fact, rapid and extensive deubiquitination of H2A occurs in Jurkat cells undergoing apoptosis initiated by, for example, anti-Fas activating antibody, staurosporine, etoposide, doxorubicin and proteasome inhibitors [99], indicating that histone deubiquitination, either H2A or H2B, is a common apoptotic trigger across evolution.

–

Histone methylation

Monoubiquitination of H2B is prerequisite to the di- and tri-methylation of histone H3 on lysine 4 (H3K4me2/3) and lysine 79 (H3K79me2/3) [59][100][101]. This crosstalk is unidirectional, as mutations that eliminate either H3 modification had no effects on the level of H2B ubiquitination [100]. H3K4 trimethylation is further regulated by monoubiquitination-independent processes: loss of H3K14 acetylation results in the specific loss of H3K4me3, but not mono- or dimethylation [102] and methylation of H3 at arginine 2 (H3R2) disables H3K4 methylation in yeast and mammalian cells [103][104][105]. H3K4me3 marks localize to the 5’ end of active genes in budding yeast and are found associated with the initiated, phosphorylated form of RNA polymerase II [106][107][108], implicating it in transcriptional elongation. It is further not only important for transcriptional activation [109][110][111][112], but also for silencing at telomeres [112][113][114] and rDNA loci [57][115][116]. Yeast cells lacking set1 are deficient in the non-homologous end joining pathway of DSB repair and are impaired in traversing S-phase of the cell cycle in the presence of replication stress [117]. In fact, set1 deficient cells have a reduced replication activity [118]. H3K4 methylation is mediated by the Set1-containing complex COMPASS (Table 1), which, in S. cerevisiae, consists of seven subunits [119][120][121][122][123] and is highly conserved among eukaryotes [61]. With respect to apoptosis it has been shown that a loss of H3K4me3 (Fig. 1) is a trigger for apoptotic cell death [33]. Strains lacking set1 (or two other members of the COMPASS complex, Spp1 and Bre2, respectively) are susceptible to Yca1-dependent apoptosis, both during chronological aging as well as in response to H2O2 treatment [33]. ∆set1 cells similarly have a shortened RLS [124]. Preventing loss of H3K4me3 by depleting the H3K4 demethylase Jhd2 on the contrary prolonged the CLS of the cells [33].

–

H3K79me3 is mediated by the methyltransferase Dot1 (Disruptor Of Telomeric silencing 1; Table 1). Dot1 is highly conserved across evolution and appears to be the sole methyltransferase responsible for H3K79 methylation [125][126][127][128][129][130]. H3K79 methylation is essential for efficient silencing near telomeres, rDNA loci, and the yeast mating type loci [113], for precise DDR [63][131][132][133][134], and in higher eukaryotes for transcriptional control of developmental genes, such as HOXA9 [108][135] and Wnt target genes [136]. Contrary to H2Bub1 and H3K4me3, H3K79me3, however, appears to play no primary role in apoptotic signalling in yeast: deletion of dot1 only slightly improves survival of wild-type cells, but it rescues ∆set1 cells from apoptotic death [33]. Furthermore, the DNA damage checkpoint kinase Rad9 and the yeast homolog of endonuclease G, Nuc1, are critical for cell death of ∆set1 cells, suggesting that loss of H3K4 methylation in the presence of H3K79 methylation and the kinase Rad9 enhances chromatin accessibility to endonuclease digestion. Importantly, wild-type, but not dot1∆ cells, loose H3K4 methylation during chronological aging, which coincides with a shorter lifespan and indicates that the loss of H3K4 methylation in fact acts as important trigger for apoptotic cell death [33].

–

A link between apoptosis and H3K4me was also observed in other species, although data here are somewhat controversial: while deficiency in MLL1, one of several H3K4 methyltransferases in mammals [137], and a lack of H3K4me3 was enhancing apoptosis induced by ER-stress [138], H3K4me3 recognition was necessary to stimulate DNA-repair after UV irradiation and to promote DNA-damage- [139][140] or genotoxic stress-induced apoptosis [141], indicating that regulation of apoptosis by H3K4 methylation may occur in a context- and/or tissue-specific manner.

–

As outlined above, replicatively aged cells have increased H2Bub1, H3K4me, and H3K79me in their telomeric heterochromatin, which is accompanied by the loss of transcriptional silencing at the telomeres. The anti-silencing activity of H2Bub, H3K4me, and H3K79me at telomeric regions is opposed by another histone methyltransferase: Set2 [35][124]. Set2 mediates methylation of H3 at K36 (Table 1) [142][143], which occurs independent of H2Bub1 [100][144]. Methylated H3K36 has been implicated in transcriptional elongation and H3K36me3 is typically found to accumulate at the 3’end of active genes in association with the phosphorylated elongating form of RNA polymerase II [142][145][146][147]. The anti-silencing function of Set2 was observed at all three heterochromatic regions in yeast and set2-depleted cells have a prolonged RLS as compared to wild-type cells [35][124]. Contrary to yeast, loss of H3K36me3 and deletion of the mediating methyltransferase met-1 shortened the lifespan of the nematode C. elegans [148], whereas loss of H3K4me3 is prolonging it [149], further supporting the context-dependency of histone modifications.

–

Histone acetylation

As outlined above, normal aging of yeast cells is accompanied by a profound loss of histone proteins [91]. The removal of histones from DNA and the incorporation of histones onto DNA are mediated by so-called histone chaperones. A highly conserved central chaperone of histones H3 and H4 is Antisilencing function 1 (Asf1), which is required for proper regulation of gene expression, acetylation of H3 on K56 (H3K56ac; Table 1), and the maintenance of genomic integrity [150][151][152]. Deletion of asf1 results in a very short CLS and a median RLS of only about 7 generations in comparison to the median life span of about 27 generations for wild-type yeast and of 15 generations for sir2 mutants [91]. Yeast lacking both asf1 and sir2 are extremely short lived with a median lifespan of 4 to 5 generations, which demonstrates that Asf1 and Sir2 are acting independently to promote longevity.

–

The role of Asf1 in determining a normal lifespan is mediated via acetylation of H3K56, which is mediated by the histone acetyltransferase (HAT) Rtt109 (Table 1) [153]. In lifespan regulation Asf1 and Rtt109 act together and a H3K56Q mutant, which mimics acetylation, has a greatly shortened lifespan. Similarly, yeast strains lacking the two redundant histone deacetylases Hst3 and Hst4 (Table 1), which leads to elevated levels of H3K56ac [154][155], die early, indicating that H3K56ac levels need to be tightly regulated [91]. H3K56ac levels appear to administer histone gene expression, which is repressed by the histone information regulator (HIR) complex [149][156]. Consequently, overexpression of the four core histones extends the median lifespan of asf1 mutants by 65% and inactivation of any component of the Hir complex (Hir1, Hir2, Hir3, Hir4, respectively) extends the median RLS of yeast cells by 25% – 35%. On the contrary, overexpression of HIR1 suppressed mRNA-instability induced apoptosis of yeast cells lacking a functional LSM4, a component of the U6 snRNA complex, during chronological aging, coinciding with a prolonged CLS [157]. How alterations in Hir proteins lead to lifespan extension on a mechanistic level remains to be seen, but it appears to be via a pathway that is independent of known lifespan regulators, such as Sir2 and the TOR pathway [91]. Interestingly, however, the loss of core histones is also directly correlated to aging of primary human fibroblasts [158].

–

Dying ∆asf1 cells not only show marks of apoptosis, but also of necrosis and they accumulate a multitude of autophagic bodies [159]. Autophagy (also called macroautophagy) is an evolutionary conserved process important for human health by which cytoplasmic contents, such as damaged organelles or aggregated proteins, are degraded by the lysosome/vacuole. Autophagy is primarily a pro-survival process, but it can also contribute to cell death, and it is becoming increasingly clear that the transcriptional regulation of autophagy-related genes is partially controlled by histone modifications and that this serves as a key determinant of survival versus death decision in autophagic cells [160]. Key in this context appears to be the loss of H3 and/or H4 acetylation, in yeast as well as in higher eukaryotes.

–

First evidence therefor came from studies on chronologically aged cells: chronologically aging and dying yeast cells show a decline in the levels of polyamines, a typical hallmark of aging across evolution [161][162][163]. Treating wild-type yeast cells with the exogenous polyamide spermidine extended the CLS due to deacetylation of histone H3 at K9, K14, and K18 through the inhibition of HATs, which coincided with suppression of oxidative stress and necrotic cell death [161]. The altered acetylation status of histone H3 led to a significant up-regulation of autophagy-related genes and consequently autophagy activation, not only in aging yeast, but also in Drosophila, C. elegans, and human cells [161]. Hyperacetylation of H3 at K14 and K18, but not K9, due to defects in acetate metabolism on the contrary led to a dramatically reduced CLS of yeast cells, which appeared to be due to the inability of the yeast mutants to induce autophagy [164][165]. This negative effect of hyperacteylated H3 on cellular aging appears conserved across species [164][165].

–

The critical linkage between histone modifications, the transcriptional regulation of autophagy-related genes and cell death is further supported by the observation that a decrease in H4K16ac due to the down-regulation of the HAT hMOF emerged from the induction of autophagy in distinct mammalian cell lines [166]. Similarly, the expression of Sas2, the yeast homolog of hMOF, and H4K16ac levels were found repressed upon autophagy induction in yeast [160][166]. The inhibition of H4K16 deacetylation in mammalian cells did not inhibit autophagy, but increased the autophagic flux, whereas reduced H4K16ac was accompanied by the down-regulation of a large number of autophagy-related genes [160][166]. Alongside with the reduction of H4K16ac also H3K4me3 is decreased upon autophagy induction in a wide variety of cells from yeast to higher eukaryotes, which may contribute to a general transcriptional inhibition to save energy during prolonged starvation [160]. Antagonizing H4K16 deacetylation by overexpressing of hMOF or by inhibiting the HDAC SIRT1, which has H4K16 as its primary histone target, resulted in increased cell death upon autophagy-induction [160][166]. In a screen using a library of histone H3-H4 yeast mutants, acetylation of H3K56 was further found reduced in cells treated with the TOR-inhibitor rapamycin, which was proposed to result from the TOR-dependent repression of the H3K56 HDACs Hst3 and Hst4 [167]. How this relates to programmed cell death remains to be seen.

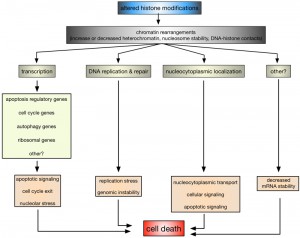

POTENTIAL DOWNSTREAM MECHANISMS OF EPIGENETIC REGULATION DURING CELL DEATH

While it is without any doubt that histone modifications are critical regulators of cell survival and death, it is only poorly understood how they and the coinciding chromatin rearrangements do so on a mechanistic level. The most obvious process influenced by alterations in histone modifications is transcription (Fig. 2).

In this context it has been shown that altered H2B ubiquitination in ∆bre1 and ∆ubp10 cells led to the enhanced expression of YCA1, likely due to the inappropriate localization of silencing complexes [34][72][73][76]. H2B ubiquitination also plays a role in p53-mediated apoptosis in human cells, although rather indirectly: knockdown of the EHF transcription factor induced p53-dependent apoptosis, whereas its overexpression is required for the survival of p53-positive colon cancer cells [168]. EHF directly activates the transcription of RUVBL1, an ATPase associated with chromatin-remodeling complexes. RUVBL1 represses transcription of p53 and its target genes by binding to the p53 promoter, as well as by interfering with RNF20/hBRE1-mediated H2B monoubiquitination and by promoting trimethylation of H3 at K9 (H3K9me3), a transcriptional silencing mark [168]. In leukaemia cells, it was furthermore shown that inhibition of DOT1L, the sole human homolog of yeast Dot1, and H3K79 methylation increased apoptosis due to down-regulation of anti-apoptotic BCL2L1 [169]. Yeast cells lacking RTT109 or ASF1 and consequently H3K56 acetylation are characterized by the repression of cell cycle genes and an accumulation of cells with in G2/M phase of the cell cycle [91], whereas H4K16 acetylation is, across species, important for the transcriptional regulation of autophagy-related genes and the subsequent survival versus death response [160][166]. Also, ribosomal DNA silencing is affected by changes in H4K16ac [77][84][86][87][91], which may lead to nucleolar stress and an apoptotic response [170]. Together these data indicate that altered histone modifications can directly influence apoptosis due to deregulated transcription of key apoptosis regulatory proteins and indirectly due to deregulation of, for example, cell cycle, autophagy, and ribosomal genes.

–

Impaired DNA DSB repair and replication defects are other nuclear processes that are influenced by histone modifications and might link them to apoptosis (Fig. 2). For example, H2B ubiquitination is required for Rad9-mediated checkpoint activation after DNA damage and Rad51-dependent DNA repair in yeast [63][64] and similarly H3K4 and H3K79 methylation have been implicated in DNA repair as well as DNA replication and recombination [171][172]. Indeed yeast cells lacking set1 and H3K4me have impaired DSB repair and are accumulating mutations [33], as well as replication defects [118], but it remains to be seen if this is related to the increase in apoptotic death of these cells.

–

Another, rather unexpected regulatory mechanism that is influenced by histone modifications appears to be altered nucleocytoplasmic localization (Fig. 2). In HeLa cells it was shown that cytochrome c, released from mitochondria upon apoptosis induction, is translocating into the nucleus, where it specifically binds acetylated H2A [173]. Nuclear, H2Aac-bound cytochrome c is causing chromatin condensation and further potentiating apoptosis [173]. The ING (Inhibitor of Growth) family of tumor suppressors acts as readers and writers of histone modifications and ING1 is a reader of H3K4me3 [139]. ING1 is a nuclear and nucleolar protein, where it exhibits apoptotic functions, and it translocates to mitochondria of primary human fibroblasts and epithelial cell lines in response to apoptosis stimuli [174]. ING1 harbors a BH3-like domain due to which it can bind pro-apoptotic Bax and promote mitochondrial membrane permeability [174]. In mammalian cells it was further shown that H2BS14ph is directly contributing to the inactivation of survival pathways, including NF-kB, due to immobilizing the RanGEF RCC1 on chromatin, thereby reducing nuclear RanGTP levels and inactivating nucleocytoplasmic transport [11].

CONCLUSION

Apoptotic cell death is accompanied by pronounced structural rearrangements within the cell, including chromatin architecture. Accumulating evidence points towards an epigenetic regulation of the chromatin remodelling events. A key player in this context appears to be monoubiquitination of histone H2B: it shelters yeast cells against intrinsic and extrinsic death stimuli. H2B monoubiquitination is prerequisite for methylation of histone H3K4 and H3K79, respectively, and H3K4 methylation appears as another vitally essential histone mark, whereas the role of H3K79 methylation is less clear. Importantly, the same histone modifications seemingly decide on the fate of higher eukaryotic cells, although context- and tissue-specific variances contribute to and complicate the particular decision. Nevertheless, these studies show that beyond the conservation of the apoptotic core machinery in yeast, also intrinsic triggers of cell death are conserved. Future studies are needed to further dissect the death code of yeast cells and most importantly to further identify and characterize the up- and downstream players that transmit the signals to and from the nucleus.

References

- B. FADEEL, and S. ORRENIUS, "Apoptosis: a basic biological phenomenon with wide‐ranging implications in human disease", Journal of Internal Medicine, vol. 258, pp. 479-517, 2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2796.2005.01570.x

- J.F. Kerr, A.H. Wyllie, and A.R. Currie, "Apoptosis: a basic biological phenomenon with wide-ranging implications in tissue kinetics.", British journal of cancer, 1972. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4561027

- A.H. Wyllie, "Glucocorticoid-induced thymocyte apoptosis is associated with endogenous endonuclease activation.", Nature, 1980. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6245367

- D.E. Olins, and A.L. Olins, "Chromatin history: our view from the bridge", Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, vol. 4, pp. 809-814, 2003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrm1225

- K. Luger, M.L. Dechassa, and D.J. Tremethick, "New insights into nucleosome and chromatin structure: an ordered state or a disordered affair?", Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, vol. 13, pp. 436-447, 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrm3382

- A.J. Bannister, and T. Kouzarides, "Regulation of chromatin by histone modifications", Cell Research, vol. 21, pp. 381-395, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/cr.2011.22

- R.K. Singh, and A. Gunjan, "Histone tyrosine phosphorylation comes of age", Epigenetics, vol. 6, pp. 153-160, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.4161/epi.6.2.13589

- J. Füllgrabe, N. Hajji, and B. Joseph, "Cracking the death code: apoptosis-related histone modifications", Cell Death & Differentiation, vol. 17, pp. 1238-1243, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/cdd.2010.58

- P. Rockenfeller, and F. Madeo, "Apoptotic death of ageing yeast", Experimental Gerontology, vol. 43, pp. 876-881, 2008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2008.08.044

- D. Carmona-Gutierrez, T. Eisenberg, S. Büttner, C. Meisinger, G. Kroemer, and F. Madeo, "Apoptosis in yeast: triggers, pathways, subroutines", Cell Death & Differentiation, vol. 17, pp. 763-773, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/cdd.2009.219

- M. Côrte-Real, and F. Madeo, "Yeast Programed Cell Death and Aging", Frontiers in Oncology, vol. 3, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2013.00283

- P. Fabrizio, and V.D. Longo, "The chronological life span of Saccharomyces cerevisiae.", Aging cell, 2003. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12882320

- M. Kaeberlein, "Lessons on longevity from budding yeast", Nature, vol. 464, pp. 513-519, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature08981

- D. Walter, S. Wissing, F. Madeo, and B. Fahrenkrog, "The inhibitor-of-apoptosis protein Bir1p protects against apoptosis in S. cerevisiae and is a substrate for the yeast homologue of Omi/HtrA2", Journal of Cell Science, vol. 119, pp. 1843-1851, 2006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1242/jcs.02902

- F. Madeo, E. Herker, C. Maldener, S. Wissing, S. Lächelt, M. Herlan, M. Fehr, K. Lauber, S.J. Sigrist, S. Wesselborg, and K. Fröhlich, "A Caspase-Related Protease Regulates Apoptosis in Yeast", Molecular Cell, vol. 9, pp. 911-917, 2002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00501-4

- K.D. Belanger, D. Walter, T.A. Henderson, A.L. Yelton, T.G. O'Brien, K.G. Belanger, S.J. Geier, and B. Fahrenkrog, "Nuclear localisation is crucial for the proapoptotic activity of the HtrA-like serine protease Nma111p", Journal of Cell Science, vol. 122, pp. 3931-3941, 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1242/jcs.056887

- S.M. Hill, X. Hao, B. Liu, and T. Nyström, "Life-span extension by a metacaspase in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae", Science, vol. 344, pp. 1389-1392, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1252634

- E. Herker, H. Jungwirth, K.A. Lehmann, C. Maldener, K. Fröhlich, S. Wissing, S. Büttner, M. Fehr, S. Sigrist, and F. Madeo, "Chronological aging leads to apoptosis in yeast", The Journal of Cell Biology, vol. 164, pp. 501-507, 2004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1083/jcb.200310014

- S. Büttner, T. Eisenberg, D. Carmona-Gutierrez, D. Ruli, H. Knauer, C. Ruckenstuhl, C. Sigrist, S. Wissing, M. Kollroser, K. Fröhlich, S. Sigrist, and F. Madeo, "Endonuclease G Regulates Budding Yeast Life and Death", Molecular Cell, vol. 25, pp. 233-246, 2007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2006.12.021

- S. Wissing, P. Ludovico, E. Herker, S. Büttner, S.M. Engelhardt, T. Decker, A. Link, A. Proksch, F. Rodrigues, M. Corte-Real, K. Fröhlich, J. Manns, C. Candé, S.J. Sigrist, G. Kroemer, and F. Madeo, "An AIF orthologue regulates apoptosis in yeast", The Journal of Cell Biology, vol. 166, pp. 969-974, 2004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1083/jcb.200404138

- S. Büttner, D. Ruli, F. Vögtle, L. Galluzzi, B. Moitzi, T. Eisenberg, O. Kepp, L. Habernig, D. Carmona-Gutierrez, P. Rockenfeller, P. Laun, M. Breitenbach, C. Khoury, K. Fröhlich, G. Rechberger, C. Meisinger, G. Kroemer, and F. Madeo, "A yeast BH3-only protein mediates the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis", The EMBO Journal, vol. 30, pp. 2779-2792, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/emboj.2011.197

- B. Fahrenkrog, U. Sauder, and U. Aebi, "TheS. cerevisiaeHtrA-like protein Nma111p is a nuclear serine protease that mediates yeast apoptosis", Journal of Cell Science, vol. 117, pp. 115-126, 2004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1242/jcs.00848

- P. Laun, A. Pichova, F. Madeo, J. Fuchs, A. Ellinger, S. Kohlwein, I. Dawes, K. Fröhlich, and M. Breitenbach, "Aged mother cells of Saccharomyces cerevisiae show markers of oxidative stress and apoptosis", Molecular Microbiology, vol. 39, pp. 1166-1173, 2001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2958.2001.02317.x

- S. Ahn, W.L. Cheung, J. Hsu, R.L. Diaz, M. Smith, and C. Allis, "Sterile 20 Kinase Phosphorylates Histone H2B at Serine 10 during Hydrogen Peroxide-Induced Apoptosis in S. cerevisiae", Cell, vol. 120, pp. 25-36, 2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.016

- S. Ahn, R.L. Diaz, M. Grunstein, and C.D. Allis, "Histone H2B Deacetylation at Lysine 11 Is Required for Yeast Apoptosis Induced by Phosphorylation of H2B at Serine 10", Molecular Cell, vol. 24, pp. 211-220, 2006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2006.09.008

- D. Walter, A. Matter, and B. Fahrenkrog, "Bre1p-mediated histone H2B ubiquitylation regulates apoptosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae", Journal of Cell Science, vol. 123, pp. 1931-1939, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1242/jcs.065938

- D. Walter, A. Matter, and B. Fahrenkrog, "Loss of Histone H3 Methylation at Lysine 4 Triggers Apoptosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae", PLoS Genetics, vol. 10, pp. e1004095, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004095

- D.E. Wright, C. Wang, and C. Kao, "Flickin’ the ubiquitin switch", Epigenetics, vol. 6, pp. 1165-1175, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.4161/epi.6.10.17745

- B. Rhie, Y. Song, H. Ryu, and S.H. Ahn, "Cellular aging is associated with increased ubiquitylation of histone H2B in yeast telomeric heterochromatin", Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, vol. 439, pp. 570-575, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.09.017

- E.P. Rogakou, W. Nieves-Neira, C. Boon, Y. Pommier, and W.M. Bonner, "Initiation of DNA Fragmentation during Apoptosis Induces Phosphorylation of H2AX Histone at Serine 139", Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 275, pp. 9390-9395, 2000. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.275.13.9390

- W.L. Cheung, K. Ajiro, K. Samejima, M. Kloc, P. Cheung, C.A. Mizzen, A. Beeser, L.D. Etkin, J. Chernoff, W.C. Earnshaw, and C. Allis, "Apoptotic Phosphorylation of Histone H2B Is Mediated by Mammalian Sterile Twenty Kinase", Cell, vol. 113, pp. 507-517, 2003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00355-6

- K. Ajiro, "Histone H2B Phosphorylation in Mammalian Apoptotic Cells", Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 275, pp. 439-443, 2000. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.275.1.439

- O. Fernandez-Capetillo, C.D. Allis, and A. Nussenzweig, "Phosphorylation of Histone H2B at DNA Double-Strand Breaks", The Journal of Experimental Medicine, vol. 199, pp. 1671-1677, 2004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1084/jem.20032247

- K. Ajiro, A.B. Scoltock, L.K. Smith, M. Ashasima, and J.A. Cidlowski, "Reciprocal epigenetic modification of histone H2B occurs in chromatin during apoptosis in vitro and in vivo", Cell Death & Differentiation, vol. 17, pp. 984-993, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/cdd.2009.199

- N. Suka, Y. Suka, A.A. Carmen, J. Wu, and M. Grunstein, "Highly Specific Antibodies Determine Histone Acetylation Site Usage in Yeast Heterochromatin and Euchromatin", Molecular Cell, vol. 8, pp. 473-479, 2001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00301-X

- C. Wong, H. Chan, C. Ho, S. Lai, K. Chan, C. Koh, and H. Li, "Apoptotic histone modification inhibits nuclear transport by regulating RCC1", Nature Cell Biology, vol. 11, pp. 36-45, 2008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ncb1810

- D. Görlich, N. Panté, U. Kutay, U. Aebi, and F.R. Bischoff, "Identification of different roles for RanGDP and RanGTP in nuclear protein import.", The EMBO journal, 1996. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8896452

- F. Melchior, B. Paschal, J. Evans, and L. Gerace, "Inhibition of nuclear protein import by nonhydrolyzable analogues of GTP and identification of the small GTPase Ran/TC4 as an essential transport factor.", The Journal of cell biology, 1993. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8276887

- M.S. Moore, and G. Blobel, "The GTP-binding protein Ran/TC4 is required for protein import into the nucleus", Nature, vol. 365, pp. 661-663, 1993. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/365661a0

- H. van Attikum, O. Fritsch, B. Hohn, and S.M. Gasser, "Recruitment of the INO80 Complex by H2A Phosphorylation Links ATP-Dependent Chromatin Remodeling with DNA Double-Strand Break Repair", Cell, vol. 119, pp. 777-788, 2004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.033

- S.P. Baker, J. Phillips, S. Anderson, Q. Qiu, J. Shabanowitz, M.M. Smith, J.R. Yates, D.F. Hunt, and P.A. Grant, "Histone H3 Thr 45 phosphorylation is a replication-associated post-translational modification in S. cerevisiae", Nature Cell Biology, vol. 12, pp. 294-298, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ncb2030

- K. Robzyk, J. Recht, and M.A. Osley, "Rad6-Dependent Ubiquitination of Histone H2B in Yeast", Science, vol. 287, pp. 501-504, 2000. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.287.5452.501

- W.W. Hwang, S. Venkatasubrahmanyam, A.G. Ianculescu, A. Tong, C. Boone, and H.D. Madhani, "A Conserved RING Finger Protein Required for Histone H2B Monoubiquitination and Cell Size Control", Molecular Cell, vol. 11, pp. 261-266, 2003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00826-2

- A. Wood, J. Schneider, J. Dover, M. Johnston, and A. Shilatifard, "The Paf1 Complex Is Essential for Histone Monoubiquitination by the Rad6-Bre1 Complex, Which Signals for Histone Methylation by COMPASS and Dot1p", Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 278, pp. 34739-34742, 2003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.C300269200

- C. Kao, C. Hillyer, T. Tsukuda, K. Henry, S. Berger, and M.A. Osley, "Rad6 plays a role in transcriptional activation through ubiquitylation of histone H2B", Genes & Development, vol. 18, pp. 184-195, 2004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gad.1149604

- K.W. Henry, A. Wyce, W. Lo, L.J. Duggan, N.T. Emre, C. Kao, L. Pillus, A. Shilatifard, M.A. Osley, and S.L. Berger, "Transcriptional activation via sequential histone H2B ubiquitylation and deubiquitylation, mediated by SAGA-associated Ubp8", Genes & Development, vol. 17, pp. 2648-2663, 2003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gad.1144003

- A. Wyce, T. Xiao, K.A. Whelan, C. Kosman, W. Walter, D. Eick, T.R. Hughes, N.J. Krogan, B.D. Strahl, and S.L. Berger, "H2B Ubiquitylation Acts as a Barrier to Ctk1 Nucleosomal Recruitment Prior to Removal by Ubp8 within a SAGA-Related Complex", Molecular Cell, vol. 27, pp. 275-288, 2007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.035

- T. Xiao, C. Kao, N.J. Krogan, Z. Sun, J.F. Greenblatt, M.A. Osley, and B.D. Strahl, "Histone H2B Ubiquitylation Is Associated with Elongating RNA Polymerase II", Molecular and Cellular Biology, vol. 25, pp. 637-651, 2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.25.2.637-651.2005

- J. Dover, J. Schneider, M.A. Tawiah-Boateng, A. Wood, K. Dean, M. Johnston, and A. Shilatifard, "Methylation of Histone H3 by COMPASS Requires Ubiquitination of Histone H2B by Rad6", Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 277, pp. 28368-28371, 2002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.C200348200

- S.D. Briggs, M. Bryk, B.D. Strahl, W.L. Cheung, J.K. Davie, S.Y. Dent, F. Winston, and C.D. Allis, "Histone H3 lysine 4 methylation is mediated by Set1 and required for cell growth and rDNA silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae", Genes & Development, vol. 15, pp. 3286-3295, 2001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gad.940201

- A.I. Mutiu, S.M.T. Hoke, J. Genereaux, G. Liang, and C.J. Brandl, "The role of histone ubiquitylation and deubiquitylation in gene expression as determined by the analysis of an HTB1 K123R Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain", Molecular Genetics and Genomics, vol. 277, pp. 491-506, 2007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00438-007-0212-6

- Z. Sun, and C.D. Allis, "Ubiquitination of histone H2B regulates H3 methylation and gene silencing in yeast", Nature, vol. 418, pp. 104-108, 2002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature00883

- M.B. Chandrasekharan, F. Huang, and Z. Sun, "Ubiquitination of histone H2B regulates chromatin dynamics by enhancing nucleosome stability", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 106, pp. 16686-16691, 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0907862106

- G.S. Shieh, C. Pan, J. Wu, Y. Sun, C. Wang, W. Hsiao, C. Lin, L. Tung, T. Chang, A.B. Fleming, C. Hillyer, Y. Lo, S.L. Berger, M.A. Osley, and C. Kao, "H2B ubiquitylation is part of chromatin architecture that marks exon-intron structure in budding yeast", BMC Genomics, vol. 12, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-12-627

- M.K. Ma, C. Heath, A. Hair, and A.G. West, "Histone Crosstalk Directed by H2B Ubiquitination Is Required for Chromatin Boundary Integrity", PLoS Genetics, vol. 7, pp. e1002175, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002175

- M. Giannattasio, F. Lazzaro, P. Plevani, and M. Muzi-Falconi, "The DNA Damage Checkpoint Response Requires Histone H2B Ubiquitination by Rad6-Bre1 and H3 Methylation by Dot1", Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 280, pp. 9879-9886, 2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M414453200

- J.C. Game, M.S. Williamson, T. Spicakova, and J.M. Brown, "The RAD6/BRE1 Histone Modification Pathway in Saccharomyces Confers Radiation Resistance Through a RAD51-Dependent Process That Is Independent of RAD18", Genetics, vol. 173, pp. 1951-1968, 2006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1534/genetics.106.057794

- K. Yamashita, M. Shinohara, and A. Shinohara, "Rad6-Bre1-mediated histone H2B ubiquitylation modulates the formation of double-strand breaks during meiosis", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 101, pp. 11380-11385, 2004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0400078101

- S. Bray, H. Musisi, and M. Bienz, "Bre1 Is Required for Notch Signaling and Histone Modification", Developmental Cell, vol. 8, pp. 279-286, 2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.devcel.2004.11.020

- S.B. Chernikova, J.A. Dorth, O.V. Razorenova, J.C. Game, and J.M. Brown, "Deficiency in Bre1 Impairs Homologous Recombination Repair and Cell Cycle Checkpoint Response to Radiation Damage in Mammalian Cells", Radiation Research, vol. 174, pp. 558-565, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1667/RR2184.1

- J. Kim, S.B. Hake, and R.G. Roeder, "The Human Homolog of Yeast BRE1 Functions as a Transcriptional Coactivator through Direct Activator Interactions", Molecular Cell, vol. 20, pp. 759-770, 2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2005.11.012

- A. Wood, N.J. Krogan, J. Dover, J. Schneider, J. Heidt, M.A. Boateng, K. Dean, A. Golshani, Y. Zhang, J.F. Greenblatt, M. Johnston, and A. Shilatifard, "Bre1, an E3 Ubiquitin Ligase Required for Recruitment and Substrate Selection of Rad6 at a Promoter", Molecular Cell, vol. 11, pp. 267-274, 2003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00802-X

- B. Zhu, Y. Zheng, A. Pham, S.S. Mandal, H. Erdjument-Bromage, P. Tempst, and D. Reinberg, "Monoubiquitination of Human Histone H2B: The Factors Involved and Their Roles in HOX Gene Regulation", Molecular Cell, vol. 20, pp. 601-611, 2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2005.09.025

- R. Fujiki, W. Hashiba, H. Sekine, A. Yokoyama, T. Chikanishi, S. Ito, Y. Imai, J. Kim, H.H. He, K. Igarashi, J. Kanno, F. Ohtake, H. Kitagawa, R.G. Roeder, M. Brown, and S. Kato, "GlcNAcylation of histone H2B facilitates its monoubiquitination", Nature, vol. 480, pp. 557-560, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature10656

- W. Burhans, "Apoptosis-like yeast cell death in response to DNA damage and replication defects", Mutation Research/Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis, vol. 532, pp. 227-243, 2003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2003.08.019

- N. Emre, K. Ingvarsdottir, A. Wyce, A. Wood, N.J. Krogan, K.W. Henry, K. Li, R. Marmorstein, J.F. Greenblatt, A. Shilatifard, and S.L. Berger, "Maintenance of Low Histone Ubiquitylation by Ubp10 Correlates with Telomere-Proximal Sir2 Association and Gene Silencing", Molecular Cell, vol. 17, pp. 585-594, 2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2005.01.007

- R.G. Gardner, Z.W. Nelson, and D.E. Gottschling, "Ubp10/Dot4p Regulates the Persistence of Ubiquitinated Histone H2B: Distinct Roles in Telomeric Silencing and General Chromatin", Molecular and Cellular Biology, vol. 25, pp. 6123-6139, 2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.25.14.6123-6139.2005

- M. BETTIGA, L. CALZARI, I. ORLANDI, L. ALBERGHINA, and M. VAI, "Involvement of the yeast metacaspase Yca1 in Δ-programmed cell death", FEMS Yeast Research, vol. 5, pp. 141-147, 2004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.femsyr.2004.07.005

- R.J. Deshaies, and C.A. Joazeiro, "RING Domain E3 Ubiquitin Ligases", Annual Review of Biochemistry, vol. 78, pp. 399-434, 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.101807.093809

- I. Orlandi, M. Bettiga, L. Alberghina, and M. Vai, "Transcriptional Profiling of ubp10 Null Mutant Reveals Altered Subtelomeric Gene Expression and Insurgence of Oxidative Stress Response", Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 279, pp. 6414-6425, 2004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M306464200

- S. Imai, C.M. Armstrong, M. Kaeberlein, and L. Guarente, "Transcriptional silencing and longevity protein Sir2 is an NAD-dependent histone deacetylase", Nature, vol. 403, pp. 795-800, 2000. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/35001622

- G. Lettre, E.A. Kritikou, M. Jaeggi, A. Calixto, A.G. Fraser, R.S. Kamath, J. Ahringer, and M.O. Hengartner, "Genome-wide RNAi identifies p53-dependent and -independent regulators of germ cell apoptosis in C. elegans", Cell Death & Differentiation, vol. 11, pp. 1198-1203, 2004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.cdd.4401488

- S.B. Chernikova, O.V. Razorenova, J.P. Higgins, B.J. Sishc, M. Nicolau, J.A. Dorth, D.A. Chernikova, S. Kwok, J.D. Brooks, S.M. Bailey, J.C. Game, and J.M. Brown, "Deficiency in Mammalian Histone H2B Ubiquitin Ligase Bre1 (Rnf20/Rnf40) Leads to Replication Stress and Chromosomal Instability", Cancer Research, vol. 72, pp. 2111-2119, 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2209

- L. Levinger, and A. Varshavsky, "Selective arrangement of ubiquitinated and D1 protein-containing nucleosomes within the Drosophila genome.", Cell, 1982. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6277512

- J.R. Davie, R. Lin, and C.D. Allis, "Timing of the appearance of ubiquitinated histones in developing new macronuclei of Tetrahymena thermophila.", Biochemistry and cell biology = Biochimie et biologie cellulaire, 1991. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1645982

- J.O. Hensold, P.S. Swerdlow, and D.E. Housman, "A transient increase in histone H2A ubiquitination is coincident with the onset of erythroleukemic cell differentiation.", Blood, 1988. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2833326

- A.P. Vassilev, H.H. Rasmussen, E.I. Christensen, S. Nielsen, and J.E. Celis, "The levels of ubiquitinated histone H2A are highly upregulated in transformed human cells: partial colocalization of uH2A clusters and PCNA/cyclin foci in a fraction of cells in S-phase.", Journal of cell science, 1995. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7622605

- Y. Marushige, and K. Marushige, "Disappearance of ubiquitinated histone H2A during chromatin condensation in TGF beta 1-induced apoptosis.", Anticancer research, 1995. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7762993

- E.G. Mimnaugh, G. Kayastha, N.B. McGovern, S. Hwang, M.G. Marcu, J. Trepel, S. Cai, V.T. Marchesi, and L. Neckers, "Caspase-dependent deubiquitination of monoubiquitinated nucleosomal histone H2A induced by diverse apoptogenic stimuli", Cell Death & Differentiation, vol. 8, pp. 1182-1196, 2001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.cdd.4400924

- S.D. Briggs, T. Xiao, Z. Sun, J.A. Caldwell, J. Shabanowitz, D.F. Hunt, C.D. Allis, and B.D. Strahl, "Trans-histone regulatory pathway in chromatin", Nature, vol. 418, pp. 498-498, 2002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature00970

- M.D. Shahbazian, K. Zhang, and M. Grunstein, "Histone H2B Ubiquitylation Controls Processive Methylation but Not Monomethylation by Dot1 and Set1", Molecular Cell, vol. 19, pp. 271-277, 2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2005.06.010

- S. Nakanishi, B.W. Sanderson, K.M. Delventhal, W.D. Bradford, K. Staehling-Hampton, and A. Shilatifard, "A comprehensive library of histone mutants identifies nucleosomal residues required for H3K4 methylation", Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, vol. 15, pp. 881-888, 2008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nsmb.1454

- E. Guccione, C. Bassi, F. Casadio, F. Martinato, M. Cesaroni, H. Schuchlautz, B. Lüscher, and B. Amati, "Methylation of histone H3R2 by PRMT6 and H3K4 by an MLL complex are mutually exclusive", Nature, vol. 449, pp. 933-937, 2007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature06166

- A. Kirmizis, H. Santos-Rosa, C.J. Penkett, M.A. Singer, M. Vermeulen, M. Mann, J. Bähler, R.D. Green, and T. Kouzarides, "Arginine methylation at histone H3R2 controls deposition of H3K4 trimethylation", Nature, vol. 449, pp. 928-932, 2007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature06160

- J. Lee, E. Smith, and A. Shilatifard, "The Language of Histone Crosstalk", Cell, vol. 142, pp. 682-685, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2010.08.011

- A. Wood, A. Shukla, J. Schneider, J.S. Lee, J.D. Stanton, T. Dzuiba, S.K. Swanson, L. Florens, M.P. Washburn, J. Wyrick, S.R. Bhaumik, and A. Shilatifard, "Ctk Complex-Mediated Regulation of Histone Methylation by COMPASS", Molecular and Cellular Biology, vol. 27, pp. 709-720, 2007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.01627-06

- T. Xiao, Y. Shibata, B. Rao, R.N. Laribee, R. O'Rourke, M.J. Buck, J.F. Greenblatt, N.J. Krogan, J.D. Lieb, and B.D. Strahl, "The RNA Polymerase II Kinase Ctk1 Regulates Positioning of a 5′ Histone Methylation Boundary along Genes", Molecular and Cellular Biology, vol. 27, pp. 721-731, 2007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.01628-06

- T. Kouzarides, "Chromatin Modifications and Their Function", Cell, vol. 128, pp. 693-705, 2007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005

- H. Santos-Rosa, R. Schneider, A.J. Bannister, J. Sherriff, B.E. Bernstein, N.C.T. Emre, S.L. Schreiber, J. Mellor, and T. Kouzarides, "Active genes are tri-methylated at K4 of histone H3", Nature, vol. 419, pp. 407-411, 2002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature01080

- B.E. Bernstein, E.L. Humphrey, R.L. Erlich, R. Schneider, P. Bouman, J.S. Liu, T. Kouzarides, and S.L. Schreiber, "Methylation of histone H3 Lys 4 in coding regions of active genes", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 99, pp. 8695-8700, 2002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.082249499

- H.H. Ng, F. Robert, R.A. Young, and K. Struhl, "Targeted Recruitment of Set1 Histone Methylase by Elongating Pol II Provides a Localized Mark and Memory of Recent Transcriptional Activity", Molecular Cell, vol. 11, pp. 709-719, 2003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00092-3

- C. Nislow, E. Ray, and L. Pillus, "SET1, a yeast member of the trithorax family, functions in transcriptional silencing and diverse cellular processes.", Molecular biology of the cell, 1997. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9398665

- M.S. Singer, A. Kahana, A.J. Wolf, L.L. Meisinger, S.E. Peterson, C. Goggin, M. Mahowald, and D.E. Gottschling, "Identification of high-copy disruptors of telomeric silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae.", Genetics, 1998. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9755194

- I.V. Mikheyeva, P.J.R. Grady, F.B. Tamburini, D.R. Lorenz, and H.P. Cam, "Multifaceted Genome Control by Set1 Dependent and Independent of H3K4 Methylation and the Set1C/COMPASS Complex", PLoS Genetics, vol. 10, pp. e1004740, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004740

- M. Bryk, S.D. Briggs, B.D. Strahl, M. Curcio, C. Allis, and F. Winston, "Evidence that Set1, a Factor Required for Methylation of Histone H3, Regulates rDNA Silencing in S. cerevisiae by a Sir2-Independent Mechanism", Current Biology, vol. 12, pp. 165-170, 2002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00652-2

- H.H. Ng, D.N. Ciccone, K.B. Morshead, M.A. Oettinger, and K. Struhl, "Lysine-79 of histone H3 is hypomethylated at silenced loci in yeast and mammalian cells: A potential mechanism for position-effect variegation", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 100, pp. 1820-1825, 2003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0437846100

- D. Faucher, and R.J. Wellinger, "Methylated H3K4, a Transcription-Associated Histone Modification, Is Involved in the DNA Damage Response Pathway", PLoS Genetics, vol. 6, pp. e1001082, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1001082

- L.F. Rizzardi, E.S. Dorn, B.D. Strahl, and J.G. Cook, "DNA Replication Origin Function Is Promoted by H3K4 Di-methylation inSaccharomyces cerevisiae", Genetics, vol. 192, pp. 371-384, 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1534/genetics.112.142349

- A. Shilatifard, "The COMPASS Family of Histone H3K4 Methylases: Mechanisms of Regulation in Development and Disease Pathogenesis", Annual Review of Biochemistry, vol. 81, pp. 65-95, 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-biochem-051710-134100

- A. Shilatifard, "Chromatin Modifications by Methylation and Ubiquitination: Implications in the Regulation of Gene Expression", Annual Review of Biochemistry, vol. 75, pp. 243-269, 2006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142422

- A. Roguev, "The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Set1 complex includes an Ash2 homologue and methylates histone 3 lysine 4", The EMBO Journal, vol. 20, pp. 7137-7148, 2001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/emboj/20.24.7137

- N.J. Krogan, J. Dover, S. Khorrami, J.F. Greenblatt, J. Schneider, M. Johnston, and A. Shilatifard, "COMPASS, a Histone H3 (Lysine 4) Methyltransferase Required for Telomeric Silencing of Gene Expression", Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 277, pp. 10753-10755, 2002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.C200023200

- T. Miller, N.J. Krogan, J. Dover, H. Erdjument-Bromage, P. Tempst, M. Johnston, J.F. Greenblatt, and A. Shilatifard, "COMPASS: A complex of proteins associated with a trithorax-related SET domain protein", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 98, pp. 12902-12907, 2001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.231473398

- H. Ryu, B. Rhie, and S.H. Ahn, "Loss of the Set2 histone methyltransferase increases cellular lifespan in yeast cells", Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, vol. 446, pp. 113-118, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.02.061

- S. Malik, and S.R. Bhaumik, "Mixed lineage leukemia: histone H3 lysine 4 methyltransferases from yeast to human", The FEBS Journal, vol. 277, pp. 1805-1821, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07607.x

- X. Wang, L. Ju, J. Fan, Y. Zhu, X. Liu, K. Zhu, M. Wu, and L. Li, "Histone H3K4 methyltransferase Mll1 regulates protein glycosylation and tunicamycin-induced apoptosis through transcriptional regulation", Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research, vol. 1843, pp. 2592-2602, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.06.013

- P. Peña, R. Hom, T. Hung, H. Lin, A. Kuo, R. Wong, O. Subach, K. Champagne, R. Zhao, V. Verkhusha, G. Li, O. Gozani, and T. Kutateladze, "Histone H3K4me3 Binding Is Required for the DNA Repair and Apoptotic Activities of ING1 Tumor Suppressor", Journal of Molecular Biology, vol. 380, pp. 303-312, 2008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2008.04.061

- S. Tyagi, and W. Herr, "E2F1 mediates DNA damage and apoptosis through HCF-1 and the MLL family of histone methyltransferases", The EMBO Journal, vol. 28, pp. 3185-3195, 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/emboj.2009.258

- T. Hung, O. Binda, K.S. Champagne, A.J. Kuo, K. Johnson, H.Y. Chang, M.D. Simon, T.G. Kutateladze, and O. Gozani, "ING4 Mediates Crosstalk between Histone H3 K4 Trimethylation and H3 Acetylation to Attenuate Cellular Transformation", Molecular Cell, vol. 33, pp. 248-256, 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2008.12.016

- B. Jones, H. Su, A. Bhat, H. Lei, J. Bajko, S. Hevi, G.A. Baltus, S. Kadam, H. Zhai, R. Valdez, S. Gonzalo, Y. Zhang, E. Li, and T. Chen, "The Histone H3K79 Methyltransferase Dot1L Is Essential for Mammalian Development and Heterochromatin Structure", PLoS Genetics, vol. 4, pp. e1000190, 2008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1000190

- G.A. Shanower, M. Muller, J.L. Blanton, V. Honti, H. Gyurkovics, and P. Schedl, "Characterization of the grappa Gene, the Drosophila Histone H3 Lysine 79 Methyltransferase", Genetics, vol. 169, pp. 173-184, 2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1534/genetics.104.033191

- F. van Leeuwen, P.R. Gafken, and D.E. Gottschling, "Dot1p Modulates Silencing in Yeast by Methylation of the Nucleosome Core", Cell, vol. 109, pp. 745-756, 2002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00759-6

- Q. Feng, H. Wang, H.H. Ng, H. Erdjument-Bromage, P. Tempst, K. Struhl, and Y. Zhang, "Methylation of H3-Lysine 79 Is Mediated by a New Family of HMTases without a SET Domain", Current Biology, vol. 12, pp. 1052-1058, 2002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0960-9822(02)00901-6

- H.H. Ng, Q. Feng, H. Wang, H. Erdjument-Bromage, P. Tempst, Y. Zhang, and K. Struhl, "Lysine methylation within the globular domain of histone H3 by Dot1 is important for telomeric silencing and Sir protein association", Genes & Development, vol. 16, pp. 1518-1527, 2002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gad.1001502

- N. Lacoste, R.T. Utley, J.M. Hunter, G.G. Poirier, and J. Côté, "Disruptor of Telomeric Silencing-1 Is a Chromatin-specific Histone H3 Methyltransferase", Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 277, pp. 30421-30424, 2002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.C200366200

- R. Wysocki, A. Javaheri, S. Allard, F. Sha, J. Côté, and S.J. Kron, "Role of Dot1-Dependent Histone H3 Methylation in G1 and S Phase DNA Damage Checkpoint Functions of Rad9", Molecular and Cellular Biology, vol. 25, pp. 8430-8443, 2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.25.19.8430-8443.2005

- Y. Huyen, O. Zgheib, R.A. DiTullio Jr, V.G. Gorgoulis, P. Zacharatos, T.J. Petty, E.A. Sheston, H.S. Mellert, E.S. Stavridi, and T.D. Halazonetis, "Methylated lysine 79 of histone H3 targets 53BP1 to DNA double-strand breaks", Nature, vol. 432, pp. 406-411, 2004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature03114

- D. Tatum, and S. Li, "Evidence That the Histone Methyltransferase Dot1 Mediates Global Genomic Repair by Methylating Histone H3 on Lysine 79", Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 286, pp. 17530-17535, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M111.241570

- S. Chaudhuri, J.J. Wyrick, and M.J. Smerdon, "Histone H3 Lys79 methylation is required for efficient nucleotide excision repair in a silenced locus of Saccharomyces cerevisiae", Nucleic Acids Research, vol. 37, pp. 1690-1700, 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkp003

- Y. Okada, Q. Feng, Y. Lin, Q. Jiang, Y. Li, V.M. Coffield, L. Su, G. Xu, and Y. Zhang, "hDOT1L Links Histone Methylation to Leukemogenesis", Cell, vol. 121, pp. 167-178, 2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.020

- M. Mohan, H. Herz, Y. Takahashi, C. Lin, K.C. Lai, Y. Zhang, M.P. Washburn, L. Florens, and A. Shilatifard, "Linking H3K79 trimethylation to Wnt signaling through a novel Dot1-containing complex (DotCom)", Genes & Development, vol. 24, pp. 574-589, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gad.1898410

- P. Oberdoerffer, and D.A. Sinclair, "The role of nuclear architecture in genomic instability and ageing", Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, vol. 8, pp. 692-702, 2007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrm2238

- S. Kim, B. Villeponteau, and S. Jazwinski, "Effect of Replicative Age on Transcriptional Silencing Near Telomeres inSaccharomyces cerevisiae", Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, vol. 219, pp. 370-376, 1996. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/bbrc.1996.0240

- T. Smeal, J. Claus, B. Kennedy, F. Cole, and L. Guarente, "Loss of transcriptional silencing causes sterility in old mother cells of S. cerevisiae.", Cell, 1996. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8598049

- S. Kim, A. Benguria, C.Y. Lai, and S.M. Jazwinski, "Modulation of life-span by histone deacetylase genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae.", Molecular biology of the cell, 1999. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10512855

- C.B. Brachmann, J.M. Sherman, S.E. Devine, E.E. Cameron, L. Pillus, and J.D. Boeke, "The SIR2 gene family, conserved from bacteria to humans, functions in silencing, cell cycle progression, and chromosome stability.", Genes & development, 1995. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7498786

- M. Bryk, M. Banerjee, M. Murphy, K.E. Knudsen, D.J. Garfinkel, and M.J. Curcio, "Transcriptional silencing of Ty1 elements in the RDN1 locus of yeast.", Genes & development, 1997. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9009207

- C.E. Fritze, "Direct evidence for SIR2 modulation of chromatin structure in yeast rDNA", The EMBO Journal, vol. 16, pp. 6495-6509, 1997. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/emboj/16.21.6495

- J.S. Smith, and J.D. Boeke, "An unusual form of transcriptional silencing in yeast ribosomal DNA.", Genes & development, 1997. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9009206

- J.S. Smith, C.B. Brachmann, L. Pillus, and J.D. Boeke, "Distribution of a limited Sir2 protein pool regulates the strength of yeast rDNA silencing and is modulated by Sir4p.", Genetics, 1998. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9649515

- M. Kaeberlein, M. McVey, and L. Guarente, "The SIR2/3/4 complex and SIR2 alone promote longevity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by two different mechanisms.", Genes & development, 1999. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10521401

- D.W. Lamming, M. Latorre-Esteves, O. Medvedik, S.N. Wong, F.A. Tsang, C. Wang, S. Lin, and D.A. Sinclair, "HST2 Mediates SIR2 -Independent Life-Span Extension by Calorie Restriction", Science, vol. 309, pp. 1861-1864, 2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1113611

- S. Gottlieb, and R.E. Esposito, "A new role for a yeast transcriptional silencer gene, SIR2, in regulation of recombination in ribosomal DNA.", Cell, 1989. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2647300

- W. Dang, K.K. Steffen, R. Perry, J.A. Dorsey, F.B. Johnson, A. Shilatifard, M. Kaeberlein, B.K. Kennedy, and S.L. Berger, "Histone H4 lysine 16 acetylation regulates cellular lifespan", Nature, vol. 459, pp. 802-807, 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature08085

- J. Feser, D. Truong, C. Das, J.J. Carson, J. Kieft, T. Harkness, and J.K. Tyler, "Elevated Histone Expression Promotes Life Span Extension", Molecular Cell, vol. 39, pp. 724-735, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2010.08.015

- J. Li, D. Moazed, and S.P. Gygi, "Association of the Histone Methyltransferase Set2 with RNA Polymerase II Plays a Role in Transcription Elongation", Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 277, pp. 49383-49388, 2002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M209294200

- B.D. Strahl, P.A. Grant, S.D. Briggs, Z. Sun, J.R. Bone, J.A. Caldwell, S. Mollah, R.G. Cook, J. Shabanowitz, D.F. Hunt, and C.D. Allis, "Set2 Is a Nucleosomal Histone H3-Selective Methyltransferase That Mediates Transcriptional Repression", Molecular and Cellular Biology, vol. 22, pp. 1298-1306, 2002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.22.5.1298-1306.2002

- H.H. Ng, R. Xu, Y. Zhang, and K. Struhl, "Ubiquitination of Histone H2B by Rad6 Is Required for Efficient Dot1-mediated Methylation of Histone H3 Lysine 79", Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 277, pp. 34655-34657, 2002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.C200433200

- B. Li, L. Howe, S. Anderson, J.R. Yates, and J.L. Workman, "The Set2 Histone Methyltransferase Functions through the Phosphorylated Carboxyl-terminal Domain of RNA Polymerase II", Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 278, pp. 8897-8903, 2003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M212134200

- D. Schaft, "The histone 3 lysine 36 methyltransferase, SET2, is involved in transcriptional elongation", Nucleic Acids Research, vol. 31, pp. 2475-2482, 2003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkg372

- T. Xiao, H. Hall, K.O. Kizer, Y. Shibata, M.C. Hall, C.H. Borchers, and B.D. Strahl, "Phosphorylation of RNA polymerase II CTD regulates H3 methylation in yeast", Genes & Development, vol. 17, pp. 654-663, 2003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gad.1055503

- M. Pu, Z. Ni, M. Wang, X. Wang, J.G. Wood, S.L. Helfand, H. Yu, and S.S. Lee, "Trimethylation of Lys36 on H3 restricts gene expression change during aging and impacts life span", Genes & Development, vol. 29, pp. 718-731, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gad.254144.114

- C. Chen, J.J. Carson, J. Feser, B. Tamburini, S. Zabaronick, J. Linger, and J.K. Tyler, "Acetylated Lysine 56 on Histone H3 Drives Chromatin Assembly after Repair and Signals for the Completion of Repair", Cell, vol. 134, pp. 231-243, 2008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.035

- C.J. Ramey, S. Howar, M. Adkins, J. Linger, J. Spicer, and J.K. Tyler, "Activation of the DNA Damage Checkpoint in Yeast Lacking the Histone Chaperone Anti-Silencing Function 1", Molecular and Cellular Biology, vol. 24, pp. 10313-10327, 2004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.24.23.10313-10327.2004

- J.K. Tyler, C.R. Adams, S. Chen, R. Kobayashi, R.T. Kamakaka, and J.T. Kadonaga, "The RCAF complex mediates chromatin assembly during DNA replication and repair", Nature, vol. 402, pp. 555-560, 1999. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/990147

- J. Schneider, P. Bajwa, F.C. Johnson, S.R. Bhaumik, and A. Shilatifard, "Rtt109 Is Required for Proper H3K56 Acetylation", Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 281, pp. 37270-37274, 2006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.C600265200

- N.L. Maas, K.M. Miller, L.G. DeFazio, and D.P. Toczyski, "Cell Cycle and Checkpoint Regulation of Histone H3 K56 Acetylation by Hst3 and Hst4", Molecular Cell, vol. 23, pp. 109-119, 2006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2006.06.006

- M. Tsuchiya, N. Dang, E.O. Kerr, D. Hu, K.K. Steffen, J.A. Oakes, B.K. Kennedy, and M. Kaeberlein, "Sirtuin‐independent effects of nicotinamide on lifespan extension from calorie restriction in yeast", Aging Cell, vol. 5, pp. 505-514, 2006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00240.x

- E.L. Greer, T.J. Maures, A.G. Hauswirth, E.M. Green, D.S. Leeman, G.S. Maro, S. Han, M.R. Banko, O. Gozani, and A. Brunet, "Members of the H3K4 trimethylation complex regulate lifespan in a germline-dependent manner in C. elegans", Nature, vol. 466, pp. 383-387, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature09195

- M.S. Spector, and M.A. Osley, "The HIR4-1 mutation defines a new class of histone regulatory genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae.", Genetics, 1993. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8224824

- M.S. Spector, A. Raff, H. DeSilva, K. Lee, and M.A. Osley, "Hir1p and Hir2p function as transcriptional corepressors to regulate histone gene transcription in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell cycle.", Molecular and cellular biology, 1997. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9001207

- R.J. O'Sullivan, S. Kubicek, S.L. Schreiber, and J. Karlseder, "Reduced histone biosynthesis and chromatin changes arising from a damage signal at telomeres", Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, vol. 17, pp. 1218-1225, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nsmb.1897

- J.A. Downs, N.F. Lowndes, and S.P. Jackson, "A role for Saccharomyces cerevisiae histone H2A in DNA repair", Nature, vol. 408, pp. 1001-1004, 2000. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/35050000

- M. Keogh, J. Kim, M. Downey, J. Fillingham, D. Chowdhury, J.C. Harrison, M. Onishi, N. Datta, S. Galicia, A. Emili, J. Lieberman, X. Shen, S. Buratowski, J.E. Haber, D. Durocher, J.F. Greenblatt, and N.J. Krogan, "A phosphatase complex that dephosphorylates γH2AX regulates DNA damage checkpoint recovery", Nature, vol. 439, pp. 497-501, 2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature04384

- G. Liang, R.J. Klose, K.E. Gardner, and Y. Zhang, "Yeast Jhd2p is a histone H3 Lys4 trimethyl demethylase", Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, vol. 14, pp. 243-245, 2007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nsmb1204

- S. Tu, E.M. Bulloch, L. Yang, C. Ren, W. Huang, P. Hsu, C. Chen, C. Liao, H. Yu, W. Lo, M.A. Freitas, and M. Tsai, "Identification of Histone Demethylases in Saccharomyces cerevisiae", Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 282, pp. 14262-14271, 2007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M609900200

- J. Lee, B. Kang, H. Jang, T.W. Kim, J. Choi, S. Kwak, J. Han, E. Cho, and H. Youn, "AKT phosphorylates H3-threonine 45 to facilitate termination of gene transcription in response to DNA damage", Nucleic Acids Research, vol. 43, pp. 4505-4516, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv176

- S. Hiraga, S. Botsios, and A.D. Donaldson, "Histone H3 lysine 56 acetylation by Rtt109 is crucial for chromosome positioning", The Journal of Cell Biology, vol. 183, pp. 641-651, 2008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1083/jcb.200806065

- M.L. Kozak, A. Chavez, W. Dang, S.L. Berger, A. Ashok, X. Guo, and F.B. Johnson, "Inactivation of the Sas2 histone acetyltransferase delays senescence driven by telomere dysfunction", The EMBO Journal, vol. 29, pp. 158-170, 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/emboj.2009.314

- A. Vaquero, R. Sternglanz, and D. Reinberg, "NAD+-dependent deacetylation of H4 lysine 16 by class III HDACs", Oncogene, vol. 26, pp. 5505-5520, 2007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.onc.1210617

- T. Eisenberg, H. Knauer, A. Schauer, S. Büttner, C. Ruckenstuhl, D. Carmona-Gutierrez, J. Ring, S. Schroeder, C. Magnes, L. Antonacci, H. Fussi, L. Deszcz, R. Hartl, E. Schraml, A. Criollo, E. Megalou, D. Weiskopf, P. Laun, G. Heeren, M. Breitenbach, B. Grubeck-Loebenstein, E. Herker, B. Fahrenkrog, K. Fröhlich, F. Sinner, N. Tavernarakis, N. Minois, G. Kroemer, and F. Madeo, "Induction of autophagy by spermidine promotes longevity", Nature Cell Biology, vol. 11, pp. 1305-1314, 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ncb1975

- F. Madeo, T. Eisenberg, S. Büttner, C. Ruckenstuhl, and G. Kroemer, "Spermidine: A novel autophagy inducer and longevity elixir", Autophagy, vol. 6, pp. 160-162, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.4161/auto.6.1.10600

- G. Scalabrino, and M.E. Ferioli, "Polyamines in mammalian ageing: An oncological problem, too? A review", Mechanisms of Ageing and Development, vol. 26, pp. 149-164, 1984. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0047-6374(84)90090-3

- T. Eisenberg, S. Schroeder, A. Andryushkova, T. Pendl, V. Küttner, A. Bhukel, G. Mariño, F. Pietrocola, A. Harger, A. Zimmermann, T. Moustafa, A. Sprenger, E. Jany, S. Büttner, D. Carmona-Gutierrez, C. Ruckenstuhl, J. Ring, W. Reichelt, K. Schimmel, T. Leeb, C. Moser, S. Schatz, L. Kamolz, C. Magnes, F. Sinner, S. Sedej, K. Fröhlich, G. Juhasz, T. Pieber, J. Dengjel, S.J. Sigrist, G. Kroemer, and F. Madeo, "Nucleocytosolic Depletion of the Energy Metabolite Acetyl-Coenzyme A Stimulates Autophagy and Prolongs Lifespan", Cell Metabolism, vol. 19, pp. 431-444, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2014.02.010

- S. Schroeder, T. Pendl, A. Zimmermann, T. Eisenberg, D. Carmona-Gutierrez, C. Ruckenstuhl, G. Mariño, F. Pietrocola, A. Harger, C. Magnes, F. Sinner, T.R. Pieber, J. Dengjel, S.J. Sigrist, G. Kroemer, and F. Madeo, "Acetyl-coenzyme A", Autophagy, vol. 10, pp. 1335-1337, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.4161/auto.28919

- J. Füllgrabe, M.A. Lynch-Day, N. Heldring, W. Li, R.B. Struijk, Q. Ma, O. Hermanson, M.G. Rosenfeld, D.J. Klionsky, and B. Joseph, "The histone H4 lysine 16 acetyltransferase hMOF regulates the outcome of autophagy", Nature, vol. 500, pp. 468-471, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature12313

- H. Chen, M. Fan, L.M. Pfeffer, and R.N. Laribee, "The histone H3 lysine 56 acetylation pathway is regulated by target of rapamycin (TOR) signaling and functions directly in ribosomal RNA biogenesis", Nucleic Acids Research, vol. 40, pp. 6534-6546, 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/gks345

- K. Taniue, T. Oda, T. Hayashi, M. Okuno, and T. Akiyama, "A member of the ETS family, EHF, and the ATPase RUVBL1 inhibit p53‐mediated apoptosis", EMBO reports, vol. 12, pp. 682-689, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/embor.2011.81

- W. Liu, L. Deng, Y. Song, and M. Redell, "DOT1L Inhibition Sensitizes MLL-Rearranged AML to Chemotherapy", PLoS ONE, vol. 9, pp. e98270, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0098270

- E.A. Prokhorova, A.V. Zamaraev, G.S. Kopeina, B. Zhivotovsky, and I.N. Lavrik, "Role of the nucleus in apoptosis: signaling and execution", Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, vol. 72, pp. 4593-4612, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00018-015-2031-y

- M.B. Chandrasekharan, F. Huang, and Z. Sun, "Histone H2B ubiquitination and beyond", Epigenetics, vol. 5, pp. 460-468, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.4161/epi.5.6.12314

- A. Wood, J. Schneider, and A. Shilatifard, "Cross-talking histones: implications for the regulation of gene expression and DNA repair", Biochemistry and Cell Biology, vol. 83, pp. 460-467, 2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1139/o05-116

- A. Nur-E-Kamal, S.R. Gross, Z. Pan, Z. Balklava, J. Ma, and L.F. Liu, "Nuclear Translocation of Cytochrome c during Apoptosis", Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 279, pp. 24911-24914, 2004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.C400051200

- P. Bose, S. Thakur, S. Thalappilly, B.Y. Ahn, S. Satpathy, X. Feng, K. Suzuki, S.W. Kim, and K. Riabowol, "ING1 induces apoptosis through direct effects at the mitochondria", Cell Death & Disease, vol. 4, pp. e788-e788, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/cddis.2013.321

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the Fonds Nationale de Recherche Scientifique (FNRS) Belgium (grant T.0237.13), the Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles (ARC 4.110.F.000092F), the Fonds Brachet and the Fonds Van Buuren.

COPYRIGHT

© 2015

Histone modifications as regulators of life and death in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by Birthe Fahrenkrog is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.