Reviews:

Microbial Cell, Vol. 5, No. 7, pp. 327 - 343; doi: 10.15698/mic2018.07.639

Shepherding DNA ends: Rif1 protects telomeres and chromosome breaks

1 Friedrich Miescher Institute for Biomedical Research, Maulbeerstrasse 66, CH-4058 Basel, Switzerland.

2 University of Basel, Petersplatz 10, CH-4003 Basel, Switzerland.

Keywords: genome stability, telomere homeostasis, DNA double-strand break repair pathway choice, non-homologous end-joining, DNA replication timing.

Abbreviations:

CDK - Cyclin-dependent kinase,

CST - Cdc13-Stn1-Ten1 complex,

CTD - C-terminal domain,

DDK - Dbf4-dependent kinase,

DDR - DNA damage response,

ds - double stranded,

DSB - DNA double-strand break,

HR - Homologous recombination,

MCM - Minichromosome maintenance complex,

MRN - MRE11-RAD50-NBS1 (mammalian complex),

MRX - Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2 (yeast complex),

NHEJ - Non-homologous end-joining,

NTD - N-terminal domain,

PP1 - Protein phosphatase 1,

Rap1 - Repressor/activator site-binding protein 1,

RBM - Rap1-binding motif,

Rif1 - Rap1-interacting factor 1,

Rif2 - Rap1-interacting factor 2,

SIR - Silent information regulator,

ss - single-stranded.

Received originally: 05/03/2018 Received in revised form: 08/05/2018

Accepted: 11/05/2018

Published: 17/05/2018

Correspondence:

Ulrich Rass, Tel: +41 61 696 17 30; orcid.org/0000-0001-9275-9062; ulrich.rass@fmi.ch

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that no competing interest exists.

Please cite this article as: Gabriele A. Fontana, Julia K. Reinert, Nicolas H. Thomä, Ulrich Rass (2018). Shepherding DNA ends: Rif1 protects telomeres and chromosome breaks. Microbial Cell: in press.

Abstract

Cells have evolved conserved mechanisms to protect DNA ends, such as those at the termini of linear chromosomes, or those at DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs). In eukaryotes, DNA ends at chromosomal termini are packaged into proteinaceous structures called telomeres. Telomeres protect chromosome ends from erosion, inadvertent activation of the cellular DNA damage response (DDR), and telomere fusion. In contrast, cells must respond to damage-induced DNA ends at DSBs by harnessing the DDR to restore chromosome integrity, avoiding genome instability and disease. Intriguingly, Rif1 (Rap1-interacting factor 1) has been implicated in telomere homeostasis as well as DSB repair. The protein was first identified in Saccharomyces cerevisiae as being part of the proteinaceous telosome. In mammals, RIF1 is not associated with intact telomeres, but was found at chromosome breaks, where RIF1 has emerged as a key mediator of pathway choice between the two evolutionary conserved DSB repair pathways of non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) and homologous recombination (HR). While this functional dichotomy has long been a puzzle, recent findings link yeast Rif1 not only to telomeres, but also to DSB repair, and mechanistic parallels likely exist. In this review, we will provide an overview of the actions of Rif1 at DNA ends and explore how exclusion of end-processing factors might be the underlying principle allowing Rif1 to fulfill diverse biological roles at telomeres and chromosome breaks.

RIF1 STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION

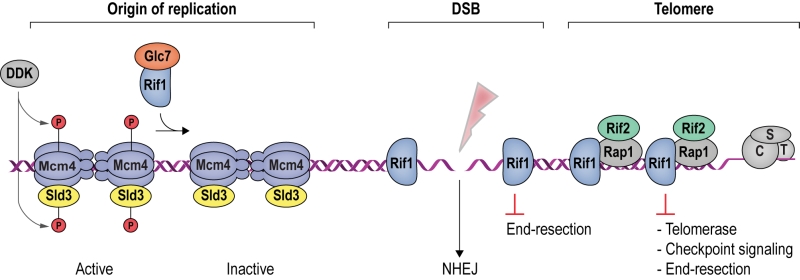

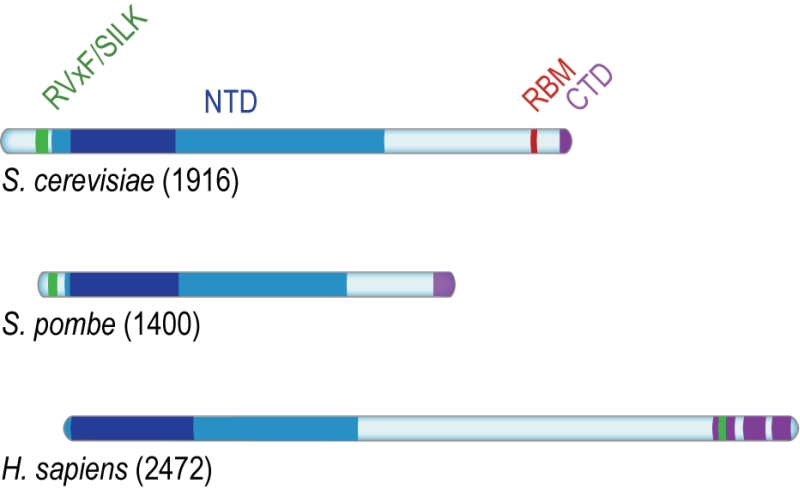

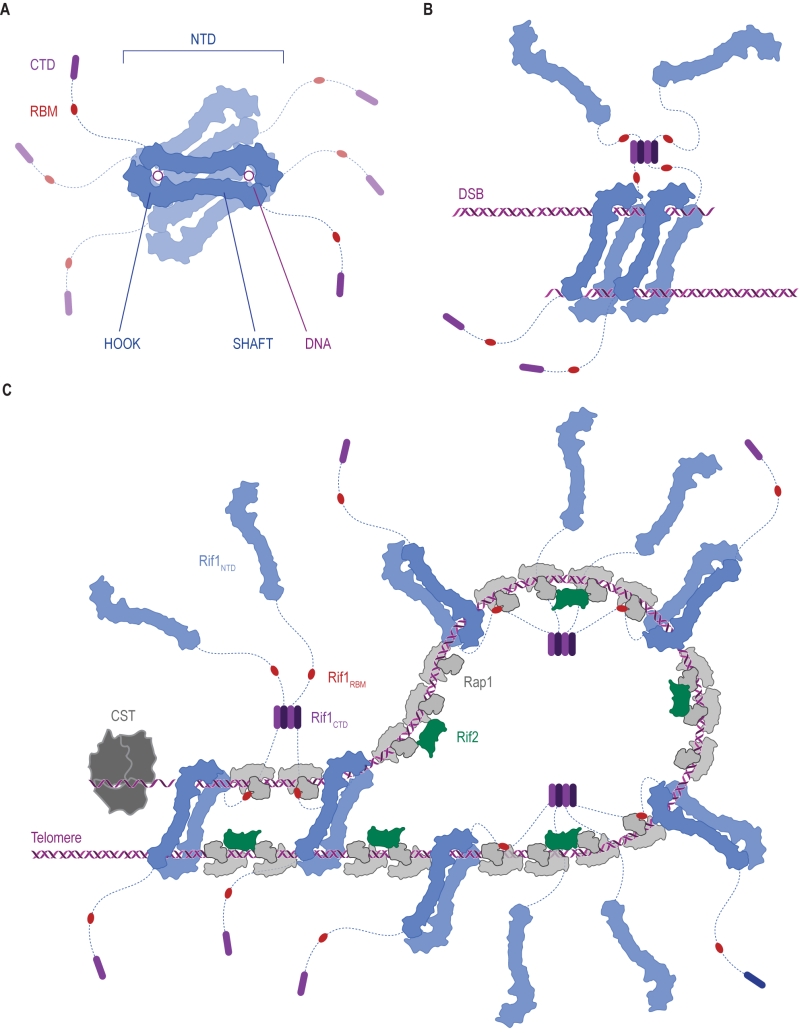

Rif1 is a multifaceted genome caretaker involved in telomere homeostasis, DSB repair pathway choice, and the regulation of replication timing (Figure 1). Rif1 orthologs in yeast [1][2] and higher eukaryotes [3][4][5][6][7] are divergent at the primary sequence level, but share key protein features. S. cerevisiae Rif1 consists of 1916 amino acids residues, has a molecular mass of 218 kDa, and contains four identifiable functional domains (Figure 2):

–

(1) RVxF/SILK protein phosphatase 1 (PP1; Glycogen 7 (Glc7) in budding yeast) docking site [8]. This site contains short KSVAF (residues 114-118) and SILR (146-149) signature sequences [6], which conform to PP1-docking motifs of the RVxF-type (consensus sequence [R/K]x[V/I/]x[F/W], where x denotes any amino acid except large hydrophobic residues) and SILK-type ([G/S]IL[R/K]) [9] (Figure 2A). A second putative RVxF/SILK domain has been identified (residues 316-320 and 222-225) [10][11]. While the position of the RVxF/SILK domains varies across organisms (Figure 3), yeast and mammalian Rif1 orthologs bind PP1, delivering phosphatase activity to origins of replication to exert control over origin firing and DNA replication timing (see Box 1 for details) [10][12][13][14][15][16][17][18]. While there is currently no evidence for an involvement of PP1 binding in the function of Rif1 in promoting DSB repair [19], a recent report indicates that Rif1-dependent recruitment of Glc7 has a role in controlling telomere homeostasis [11].

–

| In budding yeast [10][16][17][20][21], fission yeast [13][16], and mammalian cells [14][15][18][22][23], downregulation of RIF1 leads to local alterations in the temporal pattern of replication initiation, consistent with a conserved mechanism through which Rif1 regulates DNA replication timing. |

| Origins of replication are licensed in late M and G1 phase of the cell cycle, and fire in a temporally controlled manner as cells progress through S phase [24]. Origin firing requires assembly of the replicative helicase complex by association of Cdc45 (Cell division cycle 45) and GINS (Go-Ichi-Nii-San) proteins with the MCM (Minichromosome maintenance complex, comprised of Mcm2-7) catalytic core on DNA. This process is promoted by CDK and DDK (Dbf4-dependent kinase) activity. DDK-dependent phosphorylation of the unstructured Mcm4 N-terminal tail is essential for Cdc45-Mcm-GINS formation and initiation of DNA replication [25]. |

| In budding yeast, this is attenuated by Rif1, which delivers protein phosphatase PP1 (Glc7) to origins of replication, leading to the dephosphorylation of Mcm4 and Sld3 (Synthetically lethal with Dpb11-1), a factor required for Cdc45 recruitment [10][16][17] (Figure 1). Consistently, budding yeast Rif1 has been localized to the DNA replication origins that it regulates [21], and disruption of its RVxF/SILK PP1 interaction motif results in misregulated replication timing, as well as suppression of replication failure in cells with mutations in the DDK catalytic subunit [10][16][17]. While Rif1 acts in replication timing across the genome [20], telomere sequestration enhances its effect on late replicating subtelomeric DNA in budding yeast [21]. It remains to be seen whether DNA binding by the Rif1NTD [19] is involved in mediating direct interactions between Rif1 and origin DNA. Besides control over subtelomeric regions of the genome, Rif1-restricted origin firing within the heavily transcribed rDNA appears of particular importance for genome stability in budding yeast [26]. |

| In S. pombe, Rif1 controls origin firing in similar fashion with the Dis2 and Sds21 phosphatases [13][16], and the Rif1-PP1 axis is also conserved in mammalian cells [14][15][18][22][23]. Besides attenuating origin firing, human Rif1 also promotes origin licensing by stabilizing the ORC1 subunit of the origin recognition complex in G1 [18]. In addition to direct control of origin licensing/firing, Rif1 orthologs in fission yeast [27][28] and mammals [22] have been proposed to play roles in shaping nuclear architecture to facilitate the establishment of discrete, late-replicating chromatin domains. In fission yeast, this has been linked to the ability of Rif1 to bind G-quadruplex DNA, determined by chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) and in vitro DNA-binding assays [27]. Based on the ability of budding yeast Rif1 to oligomerize [29], it was proposed the interaction with multiple G-quadruplex structures could allow Rif1 to organize chromatin loops, enabling Rif1-PP1 to act not only at sites of direct DNA interaction, but over long distances [27]. This is in contrast to budding yeast, where G-quadruplex binding was not found [19], and Rif1 was detected in direct proximity of the replication origins it regulates [21]. Given previous difficulties in determining Rap1-independent genomic sites of Rif1 binding by ChIP, and the recent success of mapping Rif1 to origins by chromatin endogenous cleavage sequencing (ChEC-seq) in budding yeast [21], it would be interesting to apply ChEC-seq in the fission yeast and mammalian systems to elucidate common and distinct mechanisms of replication timing control. |

–

(2) The Rif1 N-terminal domain (NTD). In budding yeast, this domain is preceded by the RVxF/SILK motif and starts after residue 150 (Figure 2A), whereas the NTD starts at the very N-terminus of RIF1 in vertebrates [6]. The crystal structure of Rif1NTD has recently been solved (residues 177-1283), showing that this domain assumes an elongated fold composed of 23 irregular α-helical repeat units containing a mixture of two-helix HEAT (Huntingtin, elongation factor 3, protein phosphatase 2A, Tor1)-like and three-helix armadillo-like modules [19]. Overall, Rif1NTD resembles the shape of a shepherd’s crook, with the hook formed by the N-terminal end (residues 185-874; referred to as Rif1HOOK) (Figure 2B). Rif1HOOK is the most evolutionary conserved part of Rif1 and corresponds to Pfam domain Rif1_N (PF12231; residues 241-649) [30] (Figure 3). A high-affinity DNA-binding site in budding yeast Rif1 was identified within the highly positively charged concave face of the HOOK domain. Rif1NTD was co-crystallized with DNA, showing that Rif1NTD assembles into a head-to-tail dimer such that each HOOK domain forms a DNA binding channel in the resulting figure-8-shaped conformation, and this arrangement was confirmed in solution (Figure 2C). Rif1NTD binds DNA in a sequence-independent manner, and associates with double-stranded (ds) and single-stranded (ss) DNA with nanomolar affinity. Direct DNA binding was the first activity that could be ascribed to the NTD and has been linked to a range of Rif1 genome maintenance functions, including telomere homeostasis and DNA repair [19] (explained in more detail below). Recently, murine RIF1 N-terminal DNA binding has been reported [31].

–

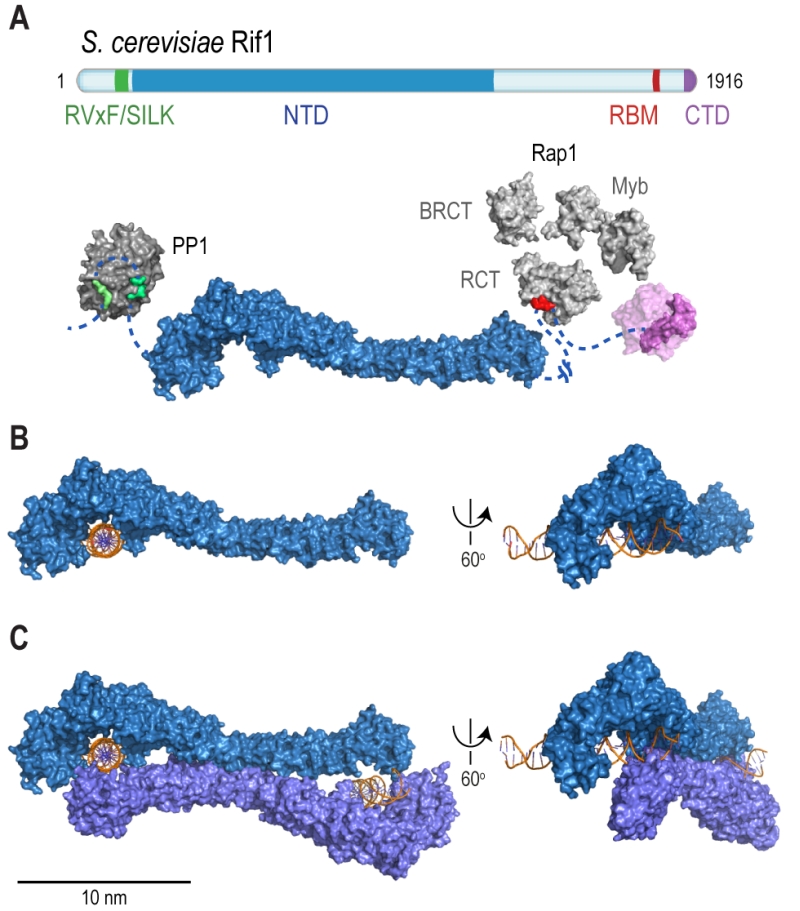

| FIGURE 2: Rif1 domains and structural features. (A) Cartoon of S. cerevisiae Rif1 with structural representation of the indicated domains: RVxF/SILK PP1/Glc7 interacting motifs (green), NTD (N-terminal domain; blue), RBM (Rap1-binding motif; red) and CTD (C-terminal domain; purple). The RVxF (residues 115-118) and SILK (residues 146-149) motifs are shown bound with protein phosphatase PP1 (dark grey), modelled on two available co-crystal structures (PDB: 4G9J for RVxF, serine/threonine-protein phosphatase PP1-alpha catalytic subunit, Homo sapiens [32] and PDB: 2O8A for SILK, serine/threonine-protein phosphatase PP1-gamma catalytic subunit, Rattus norvegicus [33]). A flexible linker connects the RVxF and SILK motifs with the NTD (residues 188-1766), which is shaped like a shepherd’s crook (PDB: 5NVR [19]). The NTD connects via a 462 residue unstructured linker with RBM (residues 1752-1772). A co-crystal structure of RBM with the Rap1 C-terminal domain (RCT) is depicted (PDB: 4BJT). In addition, Rap1 contains BRCT and Myb domains (represented in light grey, Rap1 linker regions between structured domains not shown). CTD (C-terminal domain of Rif1, residues 1857-1916, PDB: 4BJS [29]) is a tetramerization domain, allowing oligomerization with other Rif1 molecules (as indicated in translucent purple). (B) The NTD of Rif1 in complex with dsDNA. (C) Rif1NTD bound with two distinct DNA molecules in the head-to-tail dimer conformation observed in Rif1-DNA co-crystals and in solution. Contacts with the DNA are made by the concave surface of the so-called HOOK domain at the N-terminal end of the NTD [19]. |

(3) Rap1 (Repressor/activator site-binding protein 1)-binding motif (RBM, residues 1752-1772). Rap1 binds the dsDNA TG1-3 repeats at budding yeast telomeres in a sequence-specific manner and recruits Rif1 into the telosome (Figure 4). This interaction is essential for Rif1 to maintain telomere homeostasis, and disruption of Rif1RBM, which constitutes the main Rap1-binding epitope within Rif1, results in telomere dysfunction [29] (explained in more detail below). In fission yeast (Schizosaccharomyces pombe), Rif1 is recruited to telomeres by Taz1 (Telomere-associated in S. pombe 1) [2], and mammalian RIF1 is not part of the protective shelterin complex at telomeres [32]; this can explain why the Rif1RBM motif is only found in Saccharomycetes.

–

(4) The Rif1 C-terminal domain (CTD). In budding yeast, crystal structure analysis has shown that Rif1CTD (residues 1857-1916) is a tetramerization module, as well as a secondary Rap1-binding interface [1][29] (Figure 2A). In contrast to Rif1RBM, the CTD is partially conserved from yeast to human. Specifically, the vertebrate CTD can be subdivided into three regions, CTD-I, II, and III (I: amino acids 2170- 2246, II: 2274-2344, III: 2370-2446; residue numbers refer to human RIF1) (Figure 3), and CTD-II corresponds to Rif1CTD in budding yeast. CTD-I contains the canonical mammalian RVxF/SILK motif, while CTD-II was shown to have micromolar DNA-binding activity [31][33][34]. Moreover, mammalian RIF1CTD mediates an interaction with Bloom’s syndrome helicase BLM, potentially linking RIF1 to replication stress-induced DNA damage repair [33].

BUDDING YEAST RIF1 REGULATES TELOMERE HOMEOSTASIS

Rif1 underpins telomere architecture

Budding yeast telomeres contain on average 300 base pairs of repetitive TG1-3 DNA, which is bound by 15-20 Rap1 molecules. Rap1 contains three domains including a BRCT (BRCA1 C-terminal) domain, the Rap1 C-terminal domain (RCT), and a tandem myb-type helix-turn-helix domain through which the protein engages dsDNA. The short (12-15 nucleotides) telomeric ssDNA TG1-3 3ʹ overhangs are bound by the CST complex, composed of Cdc13 (Cell division cycle 13), Stn1 (Suppressor of cdc thirteen 1), and Ten1 (Telomeric pathways with Stn1). Rap1 and CST are essential genes and hypomorphs of these proteins lead to telomere dysfunction [35].

–

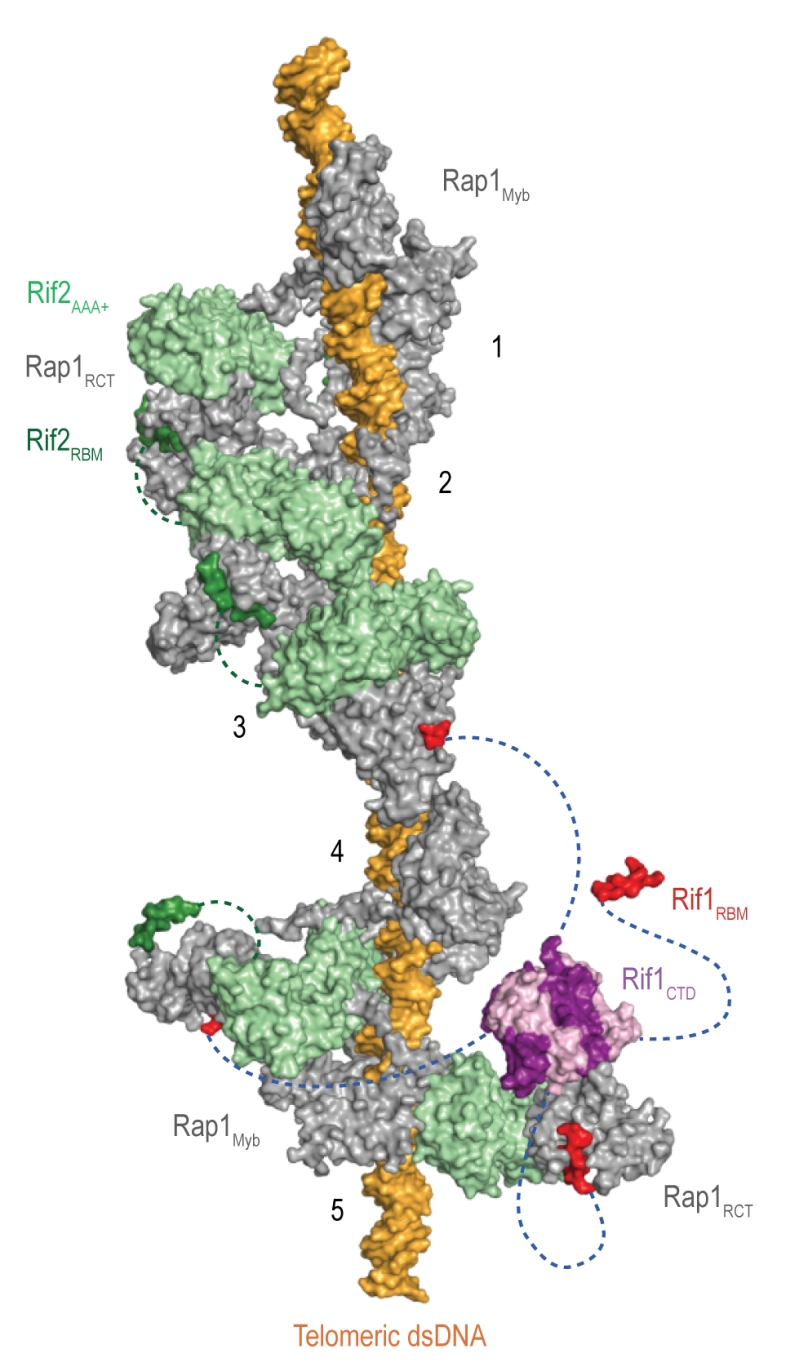

Rif1 interacts with the Rap1RCT through its RBM and CTD domains. The Rap1-binding epitope RBM is also found in Rif2 (Rap1-interacting factor 2) and the Sir (Silent information regulator) proteins, which are involved in transcriptional silencing [1][29][36][37][38]. The Rif1, Rif2, and Sir3 RBMs insert into a hydrophobic cleft within Rap1RCT in a mutually exclusive manner [29]. In addition, Rif1 and Rif2 possess secondary Rap1RCT-interaction modules: the Rif1CTD (as described above), and a AAA+ (ATPase family associated with diverse cellular activities) domain within Rif2 [29]. Through its RBM and AAA+ domains, Rif2 can interlink adjacent Rap1 molecules, while Rif1, thanks to an extended linker between its RBM and CTD domains, can engage distant Rap1 proteins. Upon tetramerization, mediated by the CTD, Rif1 can bind up to four Rap1 molecules. Each individual Rap1-binding module within Rif1 and Rif2 is required for telosome stability, indicating the importance of the interconnected, Velcro-like Rap1-Rif1-Rif2 protein network for telomere architecture and function [29] (Figure 4).

–

| Figure 4: The Velcro-like protein network found at S. cerevisiae telomeres. Structural model illustrating the Rap1-Rif1-Rif2 interactions at dsDNA regions of budding yeast telomeres [29]. Rap1 (grey) engages DNA through its Myb domain (PDB: 1IGN [41]). Numbers 1 to 5 indicate Rap1-binding sites. Rif1 and Rif2 are recruited via the Rap1RCT domain (Rap1 C-terminal domain; linker regions not shown; PDB: 4BJ5 [29]; PDB: 3UKG [42]). In this example, each Rap1RCT is bound with Rif2 (PDB: 4BJ1 [29]) via the Rif2AAA+ domain (light green). The Rif2AAA+ domain is connected to the Rif2RBM (dark green), a second Rap1 interaction epitope with similar affinity for Rap1RCT [29]. A relatively short linker between Rif2AAA+ and Rif2RBM (green dotted line, maximal length of 42 Å) limits Rif2 to interlinking neighboring Rap1 molecules. At binding site 5, more complex Rap1-Rif1-Rif2 interactions are shown in exemplary fashion. The Rif1RBM (red, PDB: 4BJT) represents the major Rap1 interaction motif; the Rif1CTD (purple, PDB: 4BJS) plays an accessory role in Rap1 binding and serves as a tetramerization domain [29]. An extended flexible linker (blue dotted line) connects the RBM and CTD domains, allowing multimeric Rif1 to interlink up to four Rap1 units over long distances (maximal distance of 110 Å). The Rif1RBM and Rif2RBM bind Rap1RCT in a mutually exclusive manner at the same hydrophobic cleft. In addition, RBM-bound Rap1RCT can engage the Rif1CTD or Rif2AAA+ domains. These multipoint interactions between interconnected Rap1, Rif1, and Rif2 stabilize the telosome and have been likened to a molecular Velcro [29]. The Rap1BRCT and Rif1NTD domains have been omitted for clarity. |

At native telomeres, Rif1 and Rif2 regulate telomere length by inhibiting telomerase in cis [36][39]. Similarly, when telomeric DNA sequences are inserted at a chromosome-internal locus that is then cleaved to expose a DNA end flanked by TG1-3 repeats, elongation of these telomeric sequences is attenuated by Rif1 and Rif2 [40][41]. Thus, Rif1 contributes to the regulation of telomerase, an enzyme which adds simple sequence repeats to chromosome ends in order to counteract telomere shortening due to the end-replication problem and nucleolytic degradation [42]. It has been observed that telomerase preferentially associates with, and elongates, short telomeres, indicating that long telomeres inhibit telomerase association more efficiently. The “protein counting” model postulates a negative feedback loop, by which the stochastic association of telomerase is increasingly suppressed when increasing amounts of Rap1, Rif1, and Rif2 are present [39][43][44][45][46][47]. Conversely, reduced Rap1-Rif1-Rif2 occupancy at short telomeres increases the chance of telomere elongation, while Rap1 phosphorylation at short telomeres provides a mechanism to strengthen Rap1-Rif1 interactions and Rif1 occupancy at telomeres [48]. With telomere elongation coinciding with replication, there is also the possibility that the unimpeded progression of replication forks through shorter telomeres may favor telomerase association and telomere elongation [49][50][51][52]. Both of these models are compatible with the Velcro-like interactions of Rap1-Rif1-Rif2, which are expected to lead to tighter telomere DNA packaging, and thus resistance to processing and/or replication factors, as telomere length (and with it Rap1-Rif1-Rif2 occupancy at chromosome ends) increases [29].

–

Rif1 inhibits telomere elongation by direct DNA binding

While the Velcro-like interactions of the Rap1-Rif1-Rif2 protein network are essential in establishing telomere architecture, the recently discovered Rif1NTD DNA-binding activity proved to be equally important for telomere length regulation [19]. It has been demonstrated that disruption of the major Rap1-interaction epitope in Rif1 (the Rif1RBM) drastically reduces Rif1 occupancy at telomeres and results in telomere elongation [29]. In contrast, Rif1NTD mutations, which reduced Rif1’s ability to bind DNA, affected telomere association less severely, but had a much stronger effect on telomere elongation, phenocopying a RIF1 deletion [19]. These observations revealed a first Rap1-independent role for Rif1 in maintaining telomere homeostasis, showing that while Rap1 interactions are important to assemble Rif1 at chromosome effectively, the ability of Rif1 to bind DNA is crucial to gate access of telomerase.

–

Rif1 suppresses checkpoint activation at telomeres

In contrast to DSB ends, where the DDR initiates a network of signaling events that block cell-cycle progression and promote DNA repair [53], telomeric ends are protected from checkpoint activation by their capping complexes. Telomere uncapping in budding yeast by mutations in the CST complex exposes chromosome ends to the DDR, resulting in checkpoint activation [54][55][56][57][58][59]. Under these conditions, an attenuation of the DDR by Rif1 can be appreciated. For example, cells carrying the hypomorphic cdc13-1 allele suffer progressive degradation of the 5ʹ-terminated strand at telomeres [55], but a full-blown DDR is prevented by Rif1, such that cells are saved from terminal checkpoint arrest and survive [60]. Rif1’s ability to suppress the lethality associated with Cdc13 dysfunction is dependent on the ability of Rif1NTD to bind DNA, while depletion of Rif1 led to telomere hyperresection [19]. Consistently, Rif1 localizes to the ssDNA/dsDNA end-resection junction and reduces the accumulation of ssDNA-binding protein RPA (Replication protein A), dampening recruitment and activation of the apical checkpoint kinase Mec1 (Mitosis entry checkpoint 1; ATR in human) [61]. Analogously, Rif1 counteracts the DDR at a model of critically short telomeres, where a DSB is induced at a short, ectopic telomeric DNA repeat sequence [41][62], and can facilitate checkpoint adaptation and cell-cycle re-entry in the presence of DNA damage [63]. The anti-checkpoint function of Rif1 in the critically-short telomere model proved to be dependent on the ability of Rif1NTD to bind DNA [19]. These observations strongly indicate that direct Rif1-DNA interactions underpin Rif1’s ability to dampen the DDR, potentially by contributing to the assembly of a proper telomere capping architecture and/or competitive exclusion of end-resection factors and checkpoint activators.

–

RIF1 and telomeres in mammals

RIF1 does not interact with the telomeric capping complex in mammalian cells, localizing to telomeres only if these are uncapped or critically short [4][5][32]. Binding at dysfunctional telomeres likely reflects the involvement of mammalian RIF1 in DSB repair rather than telomere-specific roles.

–

Nonetheless, there is an interesting link between RIF1 and telomere maintenance in mouse embryonic stem cells. In these cells, RIF1 is highly expressed [3] and helps restrict the expression of the ZSCAN4 (Zinc-finger and SCAN domain-containing 4) gene. ZSCAN4 encodes a protein that supports a recombination-dependent telomere-elongation mechanism active in mouse embryonic stem cells [64][65]. RIF1 binds to the ZSCAN4 promoter, where it interacts with components of the methyltransferase complex mediating histone H3 lysine 9 methylation (H3K9me). Thus, RIF1 facilitates H3K9me and a transcriptionally silent chromatin state at the ZSCAN4 locus, suppressing hyperrecombination, telomere elongation, and chromosome aberrations [65].

RIF1 IN DNA DOUBLE-STRAND BREAK REPAIR

Two conserved pathways mediate DSB repair

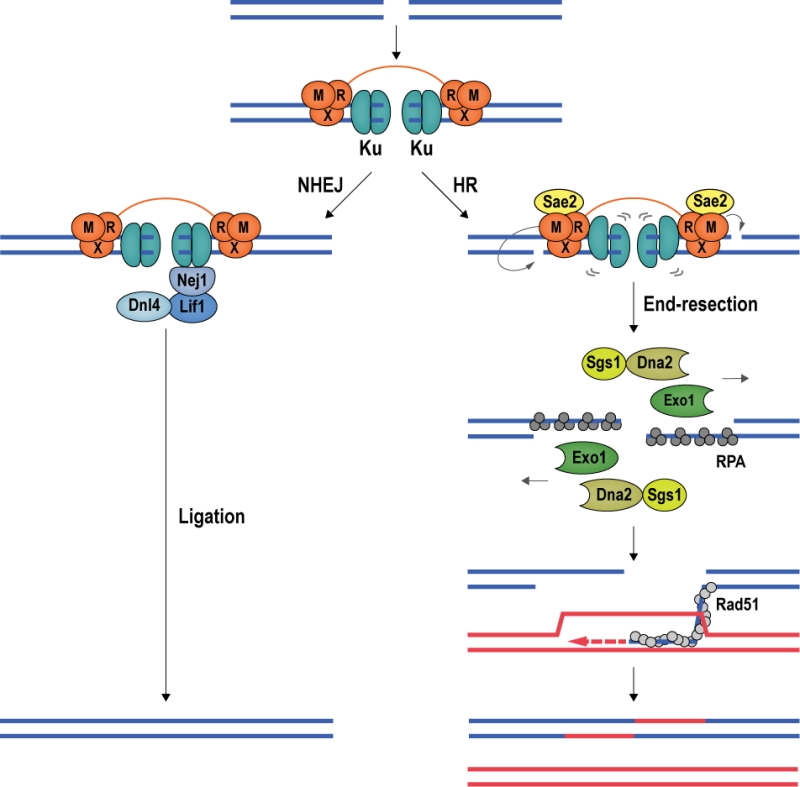

DSB repair proceeds via NHEJ or HR [66][67] (Figure 5). NHEJ is initiated by the association of the Ku heterodimer (Yku70 and Yku80) with DNA ends. Ku tightly encases DNA ends as a ring-like structure [68], forming a barrier to DNA degradation [69][70]. Moreover, Ku serves as a scaffold for the recruitment of the core NHEJ machinery, comprised of the Dnl4-Lif1 (DNA ligase 4 and ligase-interacting factor 1) ligase complex and Nej1 (Non-homologous end-joining defective 1) [71][72][73][74]. When the Ku/Dnl4-Lif1/Nej1 complex is stably formed, the break ends are aligned and ligated. NHEJ can occur in all cell-cycle phases and is the preferred repair pathway in G1 and early S phase [66] (Figure 5).

–

DSB repair by HR requires a homologous repair template, which is usually provided by the unbroken sister chromatid [75][76]; thus, HR is mainly used for DSB repair during late S and G2 phase of the cell cycle [67]. In budding yeast, the first HR factor observed at DSBs is the MRX complex [77], constituted by Mre11 (Meiotic recombination 11), Rad50 (Radiation sensitive 50), and Xrs2 (X-ray sensitive 2) (MRE11, RAD50, and NBS1 (Nijmegen breakage syndrome gene 1) in mammals). Stimulated by phosphorylated Sae2 (Sporulation in the absence of Spo eleven 2; CtIP (CtBP-interacting protein) in mammals) and Ku, Mre11 introduces an endonucleolytic nick on the 5ʹ-terminated DNA strand, initiating DNA end-resection, which leads to the eviction of Ku [78][79][80][81][82][83]. Exonuclease Exo1 and the helicase/nuclease complex constituted by Sgs1 (Slow growth suppressor 1; BLM in mammals) and Dna2 (DNA synthesis defective 2) [84] then catalyze long-range 5ʹ to 3ʹ end-resection [85][86]. In mammalian cells, MRE11 has been reported to cut both strands of the DNA in close proximity of the break, removing ends occluded by Ku and allowing EXO1 to engage for long-range end-resection [87]. The resection tracts are initially covered by RPA, which is then exchanged for the central recombinase Rad51 (Radiation sensitive 51) with the help of recombination mediator proteins. The resulting Rad51 nucleoprotein filament conducts homology search, seeking out a homologous template for DSB repair [88][89] (Figure 5).

–

DNA end-resection at DSBs determines repair pathway choice

At DSBs, repair pathway choice is intricately linked with DNA end-resection. As described above, NHEJ requires limited, if any, end processing, and becomes inefficient when DNA ends are extensively resected [90]. In contrast, HR is dependent on end-resection and exposure of ssDNA tracts, which serve as substrate for the recombination machinery. End-resection is therefore a commitment to DSB repair by HR, and in eukaryotes this commitment is linked to the cell cycle and CDK (Cyclin-dependent kinase) activity [91]. In budding yeast, the sole CDK involved in cell-cycle control, Cdc28, regulates end-resection at DSBs [92][93]. Cdc28 phosphorylates Sae2 [94], which stimulates Mre11 in nicking the 5ʹ-terminated DNA strand, providing an entry site for the end-resection nucleases Exo1 and Dna2 [78][80][81]. Cdc28 also phosphorylates Dna2, promoting long-range end-resection [95], and the chromatin remodeler Fun30 (Function unknown now 30), which counteracts an end-protection activity exerted by DDR mediator Rad9 [96][97]. As a result, end-resection and HR-mediated DSB repair are prevalent in late S and G2/M phases of the cell cycle, when CDK activity is high.

–

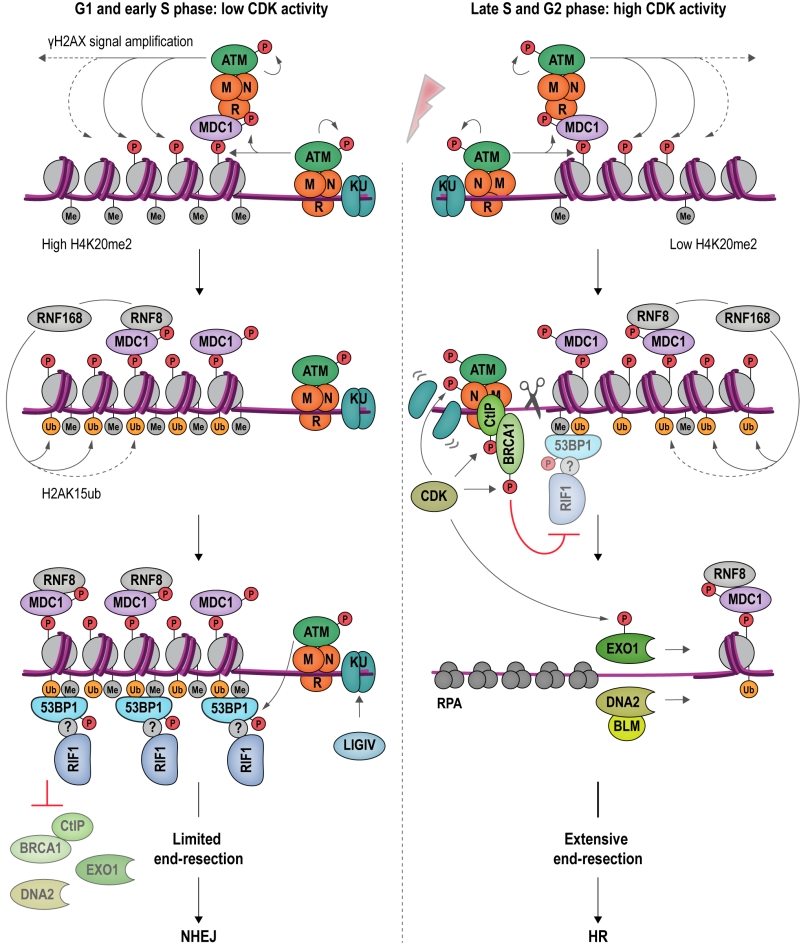

Similar CDK-dependent mechanisms promote end-resection in mammalian cells [90]. Importantly, phosphorylation of mammalian Sae2 ortholog CtIP promotes its interaction with pro-resection factor BRCA1 (Breast cancer gene 1) [98][99][100]. RIF1, in conjunction with 53BP1 (p53-binding protein 1) [101], counterbalances the BRCA1-CtIP axis of end-resection. The role of RIF1 in blocking end-resection and promoting NHEJ in mammalian cells [102] is the subject of the next section.

–

An antagonism between 53BP1-RIF1 and BRCA1-CtIP mediates DSB repair pathway choice in mammalian cells

RIF1 accumulates at DSBs in a manner dependent on apical DNA damage-checkpoint kinase ATM (Ataxia-telangiectasia mutated) and 53BP1 [4], a protein related to checkpoint mediator Rad9 in budding yeast [103] (Figure 6). ATM phosphorylates a cluster of 28 N-terminal S/T-Q sites within 53BP1 to promote RIF1 binding [4][104][105][106][107][108][109][110][111][112][113], but whether the interaction between RIF1 and 53BP1 is direct or involves as-yet unidentified accessory factors is currently not clear [114]. 53BP1 is a reader of multiple histone marks, allowing 53BP1-RIF1 recruitment to damaged chromatin surrounding DSBs in a highly controlled manner: (1) the tandem Tudor domain of 53BP1 interacts with dimethylated lysine 20 on histone 4 (H4K20me2) [115], and (2) the UDR (ubiquitylation-dependent recruitment) motif contacts mono-ubiquitylated lysine 15 on histone 2A (H2AK15ub) [116][117]; (3) it has also been reported that the C-terminal tandem BRCT (BRCA1 C-terminal) domain of 53BP1 interacts with ATM-phosphorylated histone H2AX (γH2AX) [118], however, as the BRCT domain appears to be dispensable for the recruitment of 53BP1 to damaged chromatin [107], the underlying functional relevance of this interaction remains to be elucidated. The H2AK15ub mark is specific to damaged chromatin and deposited by a ubiquitylation cascade involving RING-finger proteins RNF8 and RNF168 (Figure 6). H4K20me2 is a constitutive histone mark, which is diluted during replication due to new histone deposition in S phase. 53BP1 recruitment to sites of damage is therefore favored in G1 and less efficient in newly replicated chromatin in late S phase or G2 [119][120]. Moreover, L3MBTL1 (Lethal 3 malignant brain tumor-like protein 1) [121] and KDM4A (Lysine specific demethylase 4A) [122] compete with 53BP1 for the binding of H4K20me2, while TIRR (Tudor-interacting repair regulatory protein) binds 53BP1, masking the interaction surface for methylated H4 [123]. Recruitment of 53BP1 to chromatin is further controlled by post-translational modifications deposited on 53BP1 itself. Thus, RNF168-dependent ubiquitylation [124], and PRMT1 (Protein arginine N-methyltransferase 1)-dependent methylation [125] of 53BP1 favors its accumulation at sites of damage, while 53BP1 phosphorylation [126][127] and acetylation [128] reduce the affinity of 53BP1 for H2AK15ub.

–

Observations showing that downregulation of 53BP1 induces ectopic BRCA1 recruitment to DSBs in G1, and that conversely, depletion of BRCA1 or CtIP leads to accumulation of 53BP1 at chromosomal breaks in G2, indicate that 53BP1 and BRCA1 compete for DSB binding [112]. CDK-dependent phosphorylation of CtIP [129][130][131] favors the formation of a complex containing BRCA1, CtIP and MRN [99] at DSBs. BRCA1 and its partner BARD1 (BRCA1-associated RING domain protein 1) form an E3 ubiquitin ligase, adding ubiquitin chains to H2A. Ubiquitylated H2A attracts chromatin remodeler SMARCAD1 (SWI/SNF-related matrix-associated actin-dependent regulator of chromatin subfamily A containing DEAD/H box1; Fun30 in budding yeast), which in turn evicts and repositions nucleosomes and 53BP1 at DSBs [132]. Ubiquitylation of RIF1, promoted by BRCA1 interactor UHRF1 (Ubiquitin-like, containing PHD and RING finger domains 1), is also involved in dissociating RIF1 from DSB ends [133]. Following removal of 53BP1 and RIF1, end-resection, catalyzed by EXO1 [134][135] and DNA2-BLM [136][137][138] can take place, initiating HR repair.

–

While 53BP1 and RIF1 are epistatic in repressing end-resection at DSBs [109][113], it is not yet understood how 53BP1 and RIF1 cooperate to inhibit the end-resection machinery and promote NHEJ mechanistically. By analogy to budding yeast, where Rif1 participates in organizing higher-order structures at telomeres [29] (Figure 4), it has been speculated that 53BP1 and RIF1 might arrange DSBs into structures less accessible for resection [114]. At uncapped telomeres, resembling one-ended DSBs, RIF1’s role in attenuating end-resection is supported by BLM [33] and MAD2L2 (Mitotic spindle assembly checkpoint protein MAD2B) [139], and these interactions could putatively play similar roles at chromosome breaks. Finally, given the interaction between RIF1 and PP1 (see Box 1), it is tempting to speculate that the dephosphorylation of DDR and/or resection factors may be involved in RIF1-dependent attenuation of end-resection [102].

–

Rif1 and DSB repair pathway choice in budding yeast: Rif1 attenuates DNA end-resection by tightly encasing DNA ends

The involvement of S. cerevisiae Rif1 in DSB repair has emerged only recently. A first indication that budding yeast Rif1 may localize to broken DNA came from studies focused on the telomeric roles of Rif1. In a model for critically short telomeres, where a DSB is generated proximal to a short telomeric repeat sequence, Rif1 accumulates in a Rap1-dependent manner. Surprisingly, Rif1 was observed at these telomeric breaks even when its C-terminal Rap1-interaction modules (the Rif1RBM and Rif1CTD domains) were disrupted, which suggested a Rap1-independent mechanism of recruitment [29]. This was confirmed by findings of Rif1 targeting induced DSBs at different places in the budding yeast genome, and in a manner fully independent of telomeric DNA sequences [19][63][140].

–

In contrast to the mammalian system, a first analysis of budding yeast Rif1 at non-telomeric DSBs showed that cells deleted for RIF1 accumulated less ssDNA at distances greater than ~2 kb from a break site in G1 phase of the cell cycle [140]. This correlated with increased binding of DNA damage checkpoint mediator Rad9, a protein known for its ability to function as a barrier to end-resection [141][142]. It therefore appears that Rif1 may facilitate longer-range end-resection by limiting Rad9 recruitment under certain conditions. While this Rif1-Rad9 interplay has been shown to be important for deleterious intrachromosomal break repair, any impact on canonical DSB repair by HR or NHEJ remains unclear [140][143].

–

Further insight into the interaction of Rif1 with DSBs resulted from the identification of the Rif1NTD DNA-binding site (Figure 2). In vitro, Rif1NTD binds dsDNA and ssDNA substrates in a sequence-independent manner, showing preference for 3ʹ-tailed ssDNA-dsDNA junctions, a DNA structure similar to those found at telomeric ends and DSB ends. As mentioned above, direct DNA binding by the Rif1NTD was found to play critical in vivo roles by counteracting telomerase and the attenuation of end-resection at uncapped telomeres in budding yeast. Analogously, and mirroring the situation in mammalian systems, Rif1NTD also engages DSBs, attenuates end-resection, and promotes NHEJ [19]. In yeast strains harboring an inducible DSB that can only be repaired by NHEJ [144][145], loss of Rif1 destabilized the break ends and reduced repair by ~40%. End-protection and the promotion of NHEJ by Rif1 was dependent on the DNA-binding activity residing in the HOOK domain of Rif1NTD; in contrast, the Rap1 and PP1-binding modules are apparently not required [19]. These findings show that the role of Rif1 in modulating DSB repair pathway choice is evolutionary conserved, and that the yeast and mammalian Rif1 orthologs are functionally more similar than previously thought.

–

The structural and functional evidence in budding yeast strongly suggests that Rif1NTD promotes NHEJ by tightly encasing DNA ends in a way that sterically excludes the end-resection machinery. In human, the NTD is strictly required for recruitment of Rif1 to DSBs, while the C-terminal part of the protein contributes moderately [112]. Based on the evolutionary conservation of the Rif1NTD [6] and recent reports of DNA binding by the murine RIF1 [31], it is tempting to speculate that Rif1 may operate in DSB repair by gating access to DNA ends across organisms.

–

Possible means of regulation of budding yeast Rif1 in DSB repair

In mammalian cells, the actions of RIF1 in DSB repair pathway choice are dependent upon 53BP1 [109][111][112][113]. A potential functional equivalent to 53BP1 in budding yeast is Rad9. Like 53BP1, Rad9 is a reader of histone marks, interacting with damaged chromatin through its Tudor and BRCT domains binding H3K79me [146][147] and γH2AX [148][149], respectively. So far, no functional or physical interactions between Rad9 and Rif1 analogous to the mammalian 53BP1-RIF1 axis have been reported. Quite to the contrary, Rif1 has been shown to prevent the accumulation of Rad9 at telomeres, inhibiting the DDR [61][62]. As described above, a similar antagonism between Rif1 and Rad9 may operate at DSBs [63][140]. How yeast Rif1 is regulated in NHEJ is an interesting open question. HEAT repeats have frequently been linked with protein-protein interactions [150], raising the possibility that, in addition to direct DNA binding, RifNTD may mediate as-yet unknown physical interactions regulating its functions in NHEJ.

–

In budding yeast, Rif1 has been seen in foci at the nuclear periphery, coinciding with the subnuclear position of telomeres [151][152][153]. Fission yeast Rif1 has been proposed to establish late-replicating domains by dictating specific chromatin architectures in proximity of the inner nuclear membrane [27] (see Box 1). Similarly, mouse RIF1 proved critical in linking nuclear spatial organization and replication timing, and based on the observation that RIF1 interacts with Lamin B1, this function may be exerted by physical interactions with the inner nuclear membrane [22]. Given that nuclear compartments are important for DSB repair [154][155], it will be interesting to explore whether a nuclear-peripheral localization of Rif1 may be functionally involved in NHEJ.

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Initially described as a telomeric protein in budding yeast [1], Rif1 is now recognized as a key genome maintenance factor that exists across eukaryotes. A growing body of evidence indicates that most of Rif1’s diverse functions are evolutionary conserved. Studies in yeast [10][13][16][17][20][21] and mammalian cells [14][15][18][22][23] have provided a detailed view of Rif1 in the regulation of replication timing by shared mechanisms involving control over origin firing and chromatin structure (Box 1). Pioneering work in mammalian cells has established RIF1 as a mediator of DSB repair pathway choice [4][5][109][111][112][113]. At DSBs, RIF1 promotes NHEJ by attenuating end-resection, although the mechanism of action in mammalian cells remains to be elucidated. The yeast model may prove informative in these efforts. Budding yeast Rif1 has long been regarded purely as a telomere maintenance factor, tethered to chromosome ends by DNA-binding protein Rap1 [1][29]. With recent studies linking budding yeast Rif1 to DSB repair, this view has changed [19][63][140]. Detailed structural analyses have revealed direct DNA binding by the conserved NTD of Rif1, which, in budding yeast at least, mediates functionally important interactions with chromosome ends and DSB ends alike [19]. The crook-shaped Rif1NTD encases DNA ends (Figure 2 and Figure 7A), gating access of processing factors. This provides an elegant, direct mechanism that allows Rif1 to control diverse biological processes including telomere elongation and end-resection. Rif1NTD-mediated DNA binding may be conserved in mammals [31], and it will be important to establish how generally the mechanistic insights from budding yeast apply to other eukaryotes.

–

Rif1 binds DNA in oligomeric form [19][31]. In the Rif1-DNA co-crystal, Rif1NTD is seen in a head-to-tail dimer configuration bound with two DNA molecules [19] (Figure 2C and Figure 7A). The significance of this intriguing arrangement remains to be elucidated in vivo, but it is tempting to speculate that multipoint DNA interactions may underpin Rif1 function. For example, tethering DSB ends, as seen in case of the MRX [156][157][158][159][160][161][162] and MRN complexes [163][164][165][166], could be involved in Rif1’s role in promoting NHEJ (Figure 7B). At telomeres, higher-order chromatin structure is important for homeostasis. In mammalian cells, chromosome ends fold back on themselves and display a lariat-like structure (T-loops), generated by invasion of the 3ʹ ssDNA overhang into the dsDNA region of the telomere [167]. In human, shelterin component TRF2 (Telomeric repeat-binding factor 2) is crucial in forming and maintaining T-loops [167][168]. Similar fold-back structures exist in yeast, and in budding yeast Rif1 and Rif2 are implicated in their formation [169][170][171][172][173]. Although speculative at the moment, both Rif1 multimerization [29] and multi-point DNA binding [19], could promote the stability of higher-order telomere structures (Figure 7C), and by analogy may also support higher-order RIF1-53BP1 assemblies at repair sites.

–

In conclusion, Rif1 is emerging as a versatile and multifaceted genome maintenance protein involved in DNA replication timing, telomere maintenance, and the repair of chromosome breaks. It now appears that its cellular functions are largely conserved among eukaryotes. The way in which Rif1 is integrated into the telomere protective cap is unique to yeast. Yet, the finding that Rif1 utilizes an intrinsic DNA-binding activity within the conserved Rif1NTD to regulate telomere length and end-resection at DSBs is compatible with the view that a conserved DNA repair protein has been “hijacked” and is moonlighting in telomere homeostasis [174]. The mechanistic parallels of direct DNA binding by Rif1 in DNA repair and telomere maintenance provide a satisfyingly unified view of Rif1 shepherding DNA ends to safeguard genome stability.

References

- "A RAP1-interacting protein involved in transcriptional silencing and telomere length regulation", Trends in Genetics, vol. 8, pp. 231, 1992. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0168-9525(92)90388-K

- J. Kanoh, and F. Ishikawa, "spRap1 and spRif1, recruited to telomeres by Taz1, are essential for telomere function in fission yeast", Current Biology, vol. 11, pp. 1624-1630, 2001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00503-6

- I.R. Adams, and A. McLaren, "Identification and characterisation of mRif1: A mouse telomere‐associated protein highly expressed in germ cells and embryo‐derived pluripotent stem cells", Developmental Dynamics, vol. 229, pp. 733-744, 2004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/dvdy.10471

- J. Silverman, H. Takai, S.B. Buonomo, F. Eisenhaber, and T. de Lange, "Human Rif1, ortholog of a yeast telomeric protein, is regulated by ATM and 53BP1 and functions in the S-phase checkpoint", Genes & Development, vol. 18, pp. 2108-2119, 2004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gad.1216004

- L. Xu, and E.H. Blackburn, "Human Rif1 protein binds aberrant telomeres and aligns along anaphase midzone microtubules", The Journal of Cell Biology, vol. 167, pp. 819-830, 2004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1083/jcb.200408181

- E. Sreesankar, R. Senthilkumar, V. Bharathi, R.K. Mishra, and K. Mishra, "Functional diversification of yeast telomere associated protein, Rif1, in higher eukaryotes", BMC Genomics, vol. 13, 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-13-255

- E. Sreesankar, V. Bharathi, R.K. Mishra, and K. Mishra, "Drosophila Rif1 is an essential gene and controls late developmental events by direct interaction with PP1-87B", Scientific Reports, vol. 5, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/srep10679

- A. Hendrickx, M. Beullens, H. Ceulemans, T. Den Abt, A. Van Eynde, E. Nicolaescu, B. Lesage, and M. Bollen, "Docking Motif-Guided Mapping of the Interactome of Protein Phosphatase-1", Chemistry & Biology, vol. 16, pp. 365-371, 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.02.012

- M. Bollen, W. Peti, M.J. Ragusa, and M. Beullens, "The extended PP1 toolkit: designed to create specificity", Trends in Biochemical Sciences, vol. 35, pp. 450-458, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2010.03.002

- S. Hiraga, G.M. Alvino, F. Chang, H. Lian, A. Sridhar, T. Kubota, B.J. Brewer, M. Weinreich, M. Raghuraman, and A.D. Donaldson, "Rif1 controls DNA replication by directing Protein Phosphatase 1 to reverse Cdc7-mediated phosphorylation of the MCM complex", Genes & Development, vol. 28, pp. 372-383, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gad.231258.113

- S. Kedziora, V.K. Gali, R.H. Wilson, K.R. Clark, C.A. Nieduszynski, S. Hiraga, and A.D. Donaldson, "Rif1 acts through Protein Phosphatase 1 but independent of replication timing to suppress telomere extension in budding yeast", Nucleic Acids Research, vol. 46, pp. 3993-4003, 2018. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/gky132

- A. Breitkreutz, H. Choi, J.R. Sharom, L. Boucher, V. Neduva, B. Larsen, Z. Lin, B. Breitkreutz, C. Stark, G. Liu, J. Ahn, D. Dewar-Darch, T. Reguly, X. Tang, R. Almeida, Z.S. Qin, T. Pawson, A. Gingras, A.I. Nesvizhskii, and M. Tyers, "A Global Protein Kinase and Phosphatase Interaction Network in Yeast", Science, vol. 328, pp. 1043-1046, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1176495

- M. Hayano, Y. Kanoh, S. Matsumoto, C. Renard-Guillet, K. Shirahige, and H. Masai, "Rif1 is a global regulator of timing of replication origin firing in fission yeast", Genes & Development, vol. 26, pp. 137-150, 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gad.178491.111

- D. Cornacchia, V. Dileep, J. Quivy, R. Foti, F. Tili, R. Santarella-Mellwig, C. Antony, G. Almouzni, D.M. Gilbert, and S.B.C. Buonomo, "Mouse Rif1 is a key regulator of the replication-timing programme in mammalian cells", The EMBO Journal, vol. 31, pp. 3678-3690, 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/emboj.2012.214

- S. Yamazaki, A. Ishii, Y. Kanoh, M. Oda, Y. Nishito, and H. Masai, "Rif1 regulates the replication timing domains on the human genome", The EMBO Journal, vol. 31, pp. 3667-3677, 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/emboj.2012.180

- A. Davé, C. Cooley, M. Garg, and A. Bianchi, "Protein Phosphatase 1 Recruitment by Rif1 Regulates DNA Replication Origin Firing by Counteracting DDK Activity", Cell Reports, vol. 7, pp. 53-61, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2014.02.019

- S. Mattarocci, M. Shyian, L. Lemmens, P. Damay, D. Altintas, T. Shi, C. Bartholomew, N.H. Thomä, C. Hardy, and D. Shore, "Rif1 Controls DNA Replication Timing in Yeast through the PP1 Phosphatase Glc7", Cell Reports, vol. 7, pp. 62-69, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2014.03.010

-

S. Hiraga, T. Ly, J. Garzón, Z. Hořejší, Y. Ohkubo, A. Endo, C. Obuse, S.J. Boulton, A.I. Lamond, and A.D. Donaldson, "Human

RIF 1 and protein phosphatase 1 stimulateDNA replication origin licensing but suppress origin activation", EMBO reports, vol. 18, pp. 403-419, 2017. http://dx.doi.org/10.15252/embr.201641983 - S. Mattarocci, J.K. Reinert, R.D. Bunker, G.A. Fontana, T. Shi, D. Klein, S. Cavadini, M. Faty, M. Shyian, L. Hafner, D. Shore, N.H. Thomä, and U. Rass, "Rif1 maintains telomeres and mediates DNA repair by encasing DNA ends", Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, vol. 24, pp. 588-595, 2017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nsmb.3420

- J.M. Peace, A. Ter-Zakarian, and O.M. Aparicio, "Rif1 Regulates Initiation Timing of Late Replication Origins throughout the S. cerevisiae Genome", PLoS ONE, vol. 9, pp. e98501, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0098501

- L. Hafner, A. Lezaja, X. Zhang, L. Lemmens, M. Shyian, B. Albert, C. Follonier, J.M. Nunes, M. Lopes, D. Shore, and S. Mattarocci, "Rif1 Binding and Control of Chromosome-Internal DNA Replication Origins Is Limited by Telomere Sequestration", Cell Reports, vol. 23, pp. 983-992, 2018. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2018.03.113

- R. Foti, S. Gnan, D. Cornacchia, V. Dileep, A. Bulut-Karslioglu, S. Diehl, A. Buness, F. Klein, W. Huber, E. Johnstone, R. Loos, P. Bertone, D. Gilbert, T. Manke, T. Jenuwein, and S. Buonomo, "Nuclear Architecture Organized by Rif1 Underpins the Replication-Timing Program", Molecular Cell, vol. 61, pp. 260-273, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2015.12.001

- R.C. Alver, G.S. Chadha, P.J. Gillespie, and J.J. Blow, "Reversal of DDK-Mediated MCM Phosphorylation by Rif1-PP1 Regulates Replication Initiation and Replisome Stability Independently of ATR/Chk1", Cell Reports, vol. 18, pp. 2508-2520, 2017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2017.02.042

- S.P. Bell, and K. Labib, "Chromosome Duplication inSaccharomyces cerevisiae", Genetics, vol. 203, pp. 1027-1067, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1534/genetics.115.186452

- Y. Sheu, and B. Stillman, "The Dbf4–Cdc7 kinase promotes S phase by alleviating an inhibitory activity in Mcm4", Nature, vol. 463, pp. 113-117, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature08647

- M. Shyian, S. Mattarocci, B. Albert, L. Hafner, A. Lezaja, M. Costanzo, C. Boone, and D. Shore, "Budding Yeast Rif1 Controls Genome Integrity by Inhibiting rDNA Replication", PLOS Genetics, vol. 12, pp. e1006414, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1006414

- Y. Kanoh, S. Matsumoto, R. Fukatsu, N. Kakusho, N. Kono, C. Renard-Guillet, K. Masuda, K. Iida, K. Nagasawa, K. Shirahige, and H. Masai, "Rif1 binds to G quadruplexes and suppresses replication over long distances", Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, vol. 22, pp. 889-897, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nsmb.3102

- T. Toteva, B. Mason, Y. Kanoh, P. Brøgger, D. Green, J. Verhein-Hansen, H. Masai, and G. Thon, "Establishment of expression-state boundaries by Rif1 and Taz1 in fission yeast", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 114, pp. 1093-1098, 2017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1614837114

- T. Shi, R. Bunker, S. Mattarocci, C. Ribeyre, M. Faty, H. Gut, A. Scrima, U. Rass, S. Rubin, D. Shore, and N. Thomä, "Rif1 and Rif2 Shape Telomere Function and Architecture through Multivalent Rap1 Interactions", Cell, vol. 153, pp. 1340-1353, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.007

- R.D. Finn, P. Coggill, R.Y. Eberhardt, S.R. Eddy, J. Mistry, A.L. Mitchell, S.C. Potter, M. Punta, M. Qureshi, A. Sangrador-Vegas, G.A. Salazar, J. Tate, and A. Bateman, "The Pfam protein families database: towards a more sustainable future", Nucleic Acids Research, vol. 44, pp. D279-D285, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv1344

- K. Moriyama, N. Yoshizawa-Sugata, and H. Masai, "Oligomer formation and G-quadruplex binding by purified murine Rif1 protein, a key organizer of higher-order chromatin architecture", Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 293, pp. 3607-3624, 2018. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.RA117.000446

- T. de Lange, "Shelterin: the protein complex that shapes and safeguards human telomeres", Genes & Development, vol. 19, pp. 2100-2110, 2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gad.1346005

- D. Xu, P. Muniandy, E. Leo, J. Yin, S. Thangavel, X. Shen, M. Ii, K. Agama, R. Guo, D. Fox, A.R. Meetei, L. Wilson, H. Nguyen, N. Weng, S.J. Brill, L. Li, A. Vindigni, Y. Pommier, M. Seidman, and W. Wang, "Rif1 provides a new DNA-binding interface for the Bloom syndrome complex to maintain normal replication", The EMBO Journal, vol. 29, pp. 3140-3155, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/emboj.2010.186

- R. Sukackaite, M.R. Jensen, P.J. Mas, M. Blackledge, S.B. Buonomo, and D.J. Hart, "Structural and Biophysical Characterization of Murine Rif1 C Terminus Reveals High Specificity for DNA Cruciform Structures", Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 289, pp. 13903-13911, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M114.557843

- R.J. Wellinger, and V.A. Zakian, "Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About Saccharomyces cerevisiae Telomeres: Beginning to End", Genetics, vol. 191, pp. 1073-1105, 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1534/genetics.111.137851

- D. Wotton, and D. Shore, "A novel Rap1p-interacting factor, Rif2p, cooperates with Rif1p to regulate telomere length in Saccharomyces cerevisiae.", Genes & Development, vol. 11, pp. 748-760, 1997. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gad.11.6.748

- E.A. Feeser, and C. Wolberger, "Structural and Functional Studies of the Rap1 C-Terminus Reveal Novel Separation-of-Function Mutants", Journal of Molecular Biology, vol. 380, pp. 520-531, 2008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2008.04.078

- Y. Chen, R. Rai, Z. Zhou, J. Kanoh, C. Ribeyre, Y. Yang, H. Zheng, P. Damay, F. Wang, H. Tsujii, Y. Hiraoka, D. Shore, H. Hu, S. Chang, and M. Lei, "A conserved motif within RAP1 has diversified roles in telomere protection and regulation in different organisms", Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, vol. 18, pp. 213-221, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nsmb.1974

- M. Teixeira, M. Arneric, P. Sperisen, and J. Lingner, "Telomere Length Homeostasis Is Achieved via a Switch between Telomerase- Extendible and -Nonextendible States", Cell, vol. 117, pp. 323-335, 2004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00334-4

- S. Negrini, V. Ribaud, A. Bianchi, and D. Shore, "DNA breaks are masked by multiple Rap1 binding in yeast: implications for telomere capping and telomerase regulation", Genes & Development, vol. 21, pp. 292-302, 2007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gad.400907

- Y. Hirano, K. Fukunaga, and K. Sugimoto, "Rif1 and Rif2 Inhibit Localization of Tel1 to DNA Ends", Molecular Cell, vol. 33, pp. 312-322, 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2008.12.027

- N. Hug, and J. Lingner, "Telomere length homeostasis", Chromosoma, vol. 115, pp. 413-425, 2006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00412-006-0067-3

- S. Marcand, E. Gilson, and D. Shore, "A Protein-Counting Mechanism for Telomere Length Regulation in Yeast", Science, vol. 275, pp. 986-990, 1997. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.275.5302.986

- S. Marcand, "Progressive cis-inhibition of telomerase upon telomere elongation", The EMBO Journal, vol. 18, pp. 3509-3519, 1999. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/emboj/18.12.3509

- M. Sabourin, C.T. Tuzon, and V.A. Zakian, "Telomerase and Tel1p Preferentially Associate with Short Telomeres in S. cerevisiae", Molecular Cell, vol. 27, pp. 550-561, 2007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2007.07.016

- J.S. McGee, J.A. Phillips, A. Chan, M. Sabourin, K. Paeschke, and V.A. Zakian, "Reduced Rif2 and lack of Mec1 target short telomeres for elongation rather than double-strand break repair", Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, vol. 17, pp. 1438-1445, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nsmb.1947

- A. Bianchi, and D. Shore, "Increased association of telomerase with short telomeres in yeast", Genes & Development, vol. 21, pp. 1726-1730, 2007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gad.438907

- C. Yang, S. Tseng, C. Yu, C. Chung, C. Chang, S. Pobiega, and S. Teng, "Telomere shortening triggers a feedback loop to enhance end protection", Nucleic Acids Research, vol. 45, pp. 8314-8328, 2017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkx503

- I. Dionne, and R.J. Wellinger, "Processing of telomeric DNA ends requires the passage of a replication fork", Nucleic Acids Research, vol. 26, pp. 5365-5371, 1998. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/26.23.5365

- S. Marcand, V. Brevet, C. Mann, and E. Gilson, "Cell cycle restriction of telomere elongation.", Current biology : CB, 2000. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10801419

- A. Bianchi, and D. Shore, "Early Replication of Short Telomeres in Budding Yeast", Cell, vol. 128, pp. 1051-1062, 2007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.041

- C.W. Greider, "Regulating telomere length from the inside out: the replication fork model", Genes & Development, vol. 30, pp. 1483-1491, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gad.280578.116

- N. Hustedt, S. Gasser, and K. Shimada, "Replication Checkpoint: Tuning and Coordination of Replication Forks in S Phase", Genes, vol. 4, pp. 388-434, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/genes4030388

- T.A. Weinert, G.L. Kiser, and L.H. Hartwell, "Mitotic checkpoint genes in budding yeast and the dependence of mitosis on DNA replication and repair.", Genes & Development, vol. 8, pp. 652-665, 1994. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gad.8.6.652

- B. Garvik, M. Carson, and L. Hartwell, "Single-Stranded DNA Arising at Telomeres in cdc13 Mutants May Constitute a Specific Signal for the RAD9 Checkpoint", Molecular and Cellular Biology, vol. 15, pp. 6128-6138, 1995. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.15.11.6128

- D. Lydall, and T. Weinert, "Yeast Checkpoint Genes in DNA Damage Processing: Implications for Repair and Arrest", Science, vol. 270, pp. 1488-1491, 1995. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.270.5241.1488

- N. Grandin, S.I. Reed, and M. Charbonneau, "Stn1, a new Saccharomyces cerevisiae protein, is implicated in telomere size regulation in association with Cdc13.", Genes & Development, vol. 11, pp. 512-527, 1997. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gad.11.4.512

- M.D. Vodenicharov, and R.J. Wellinger, "DNA Degradation at Unprotected Telomeres in Yeast Is Regulated by the CDK1 (Cdc28/Clb) Cell-Cycle Kinase", Molecular Cell, vol. 24, pp. 127-137, 2006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2006.07.035

- L. Xu, R.C. Petreaca, H.J. Gasparyan, S. Vu, and C.I. Nugent, "TEN1Is Essential forCDC13-Mediated Telomere Capping", Genetics, vol. 183, pp. 793-810, 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1534/genetics.109.108894

- S. Anbalagan, D. Bonetti, G. Lucchini, and M.P. Longhese, "Rif1 Supports the Function of the CST Complex in Yeast Telomere Capping", PLoS Genetics, vol. 7, pp. e1002024, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002024

- Y. Xue, M.D. Rushton, and L. Maringele, "A Novel Checkpoint and RPA Inhibitory Pathway Regulated by Rif1", PLoS Genetics, vol. 7, pp. e1002417, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002417

- C. Ribeyre, and D. Shore, "Anticheckpoint pathways at telomeres in yeast", Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, vol. 19, pp. 307-313, 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nsmb.2225

- Y. Xue, M.E. Marvin, I.G. Ivanova, D. Lydall, E.J. Louis, and L. Maringele, "Rif1 and Exo1 regulate the genomic instability following telomere losses", Aging Cell, vol. 15, pp. 553-562, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/acel.12466

- M. Zalzman, G. Falco, L.V. Sharova, A. Nishiyama, M. Thomas, S. Lee, C.A. Stagg, H.G. Hoang, H. Yang, F.E. Indig, R.P. Wersto, and M.S.H. Ko, "Zscan4 regulates telomere elongation and genomic stability in ES cells", Nature, vol. 464, pp. 858-863, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature08882

- J. Dan, Y. Liu, N. Liu, M. Chiourea, M. Okuka, T. Wu, X. Ye, C. Mou, L. Wang, L. Wang, Y. Yin, J. Yuan, B. Zuo, F. Wang, Z. Li, X. Pan, Z. Yin, L. Chen, D. Keefe, S. Gagos, A. Xiao, and L. Liu, "Rif1 Maintains Telomere Length Homeostasis of ESCs by Mediating Heterochromatin Silencing", Developmental Cell, vol. 29, pp. 7-19, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.devcel.2014.03.004

- J.M. Daley, P.L. Palmbos, D. Wu, and T.E. Wilson, "Nonhomologous End Joining in Yeast", Annual Review of Genetics, vol. 39, pp. 431-451, 2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.genet.39.073003.113340

- J.E. Haber, "A Life Investigating Pathways That Repair Broken Chromosomes", Annual Review of Genetics, vol. 50, pp. 1-28, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-genet-120215-035043

- J.R. Walker, R.A. Corpina, and J. Goldberg, "Structure of the Ku heterodimer bound to DNA and its implications for double-strand break repair", Nature, vol. 412, pp. 607-614, 2001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/35088000

- M. Clerici, D. Mantiero, I. Guerini, G. Lucchini, and M.P. Longhese, "The Yku70–Yku80 complex contributes to regulate double‐strand break processing and checkpoint activation during the cell cycle", EMBO reports, vol. 9, pp. 810-818, 2008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/embor.2008.121

- E.P. Mimitou, and L.S. Symington, "Ku prevents Exo1 and Sgs1-dependent resection of DNA ends in the absence of a functional MRX complex or Sae2", The EMBO Journal, vol. 29, pp. 3358-3369, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/emboj.2010.193

- T.E. Wilson, U. Grawunder, and M.R. Lieber, "Yeast DNA ligase IV mediates non-homologous DNA end joining", Nature, vol. 388, pp. 495-498, 1997. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/41365

- G. Herrmann, T. Lindahl, and P. Schär, "Saccharomyces cerevisiae LIF1: a function involved in DNA double-strand break repair related to mammalian XRCC4", The EMBO Journal, vol. 17, pp. 4188-4198, 1998. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/emboj/17.14.4188

- Y. Zhang, M.L. Hefferin, L. Chen, E.Y. Shim, H. Tseng, Y. Kwon, P. Sung, S.E. Lee, and A.E. Tomkinson, "Role of Dnl4–Lif1 in nonhomologous end-joining repair complex assembly and suppression of homologous recombination", Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, vol. 14, pp. 639-646, 2007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nsmb1261

- D. Wu, L.M. Topper, and T.E. Wilson, "Recruitment and Dissociation of Nonhomologous End Joining Proteins at a DNA Double-Strand Break in Saccharomyces cerevisiae", Genetics, vol. 178, pp. 1237-1249, 2008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1534/genetics.107.083535

- L.C. Kadyk, and L.H. Hartwell, "Sister chromatids are preferred over homologs as substrates for recombinational repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae.", Genetics, 1992. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1427035

- R.D. Johnson, "Sister chromatid gene conversion is a prominent double-strand break repair pathway in mammalian cells", The EMBO Journal, vol. 19, pp. 3398-3407, 2000. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/emboj/19.13.3398

- M. Lisby, J.H. Barlow, R.C. Burgess, and R. Rothstein, "Choreography of the DNA Damage Response", Cell, vol. 118, pp. 699-713, 2004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.015

- V. Garcia, S.E.L. Phelps, S. Gray, and M.J. Neale, "Bidirectional resection of DNA double-strand breaks by Mre11 and Exo1", Nature, vol. 479, pp. 241-244, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature10515

- A. Balestrini, D. Ristic, I. Dionne, X. Liu, C. Wyman, R. Wellinger, and J. Petrini, "The Ku Heterodimer and the Metabolism of Single-Ended DNA Double-Strand Breaks", Cell Reports, vol. 3, pp. 2033-2045, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2013.05.026

- E. Cannavo, and P. Cejka, "Sae2 promotes dsDNA endonuclease activity within Mre11–Rad50–Xrs2 to resect DNA breaks", Nature, vol. 514, pp. 122-125, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature13771

- P. Chanut, S. Britton, J. Coates, S.P. Jackson, and P. Calsou, "Coordinated nuclease activities counteract Ku at single-ended DNA double-strand breaks", Nature Communications, vol. 7, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ncomms12889

- G. Reginato, E. Cannavo, and P. Cejka, "Physiological protein blocks direct the Mre11–Rad50–Xrs2 and Sae2 nuclease complex to initiate DNA end resection", Genes & Development, vol. 31, pp. 2325-2330, 2017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gad.308254.117

- W. Wang, J.M. Daley, Y. Kwon, D.S. Krasner, and P. Sung, "Plasticity of the Mre11–Rad50–Xrs2–Sae2 nuclease ensemble in the processing of DNA-bound obstacles", Genes & Development, vol. 31, pp. 2331-2336, 2017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gad.307900.117

- E.Y. Shim, W. Chung, M.L. Nicolette, Y. Zhang, M. Davis, Z. Zhu, T.T. Paull, G. Ira, and S.E. Lee, "Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mre11/Rad50/Xrs2 and Ku proteins regulate association of Exo1 and Dna2 with DNA breaks", The EMBO Journal, vol. 29, pp. 3370-3380, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/emboj.2010.219

- Z. Zhu, W. Chung, E.Y. Shim, S.E. Lee, and G. Ira, "Sgs1 Helicase and Two Nucleases Dna2 and Exo1 Resect DNA Double-Strand Break Ends", Cell, vol. 134, pp. 981-994, 2008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.037

- E.P. Mimitou, and L.S. Symington, "Sae2, Exo1 and Sgs1 collaborate in DNA double-strand break processing", Nature, vol. 455, pp. 770-774, 2008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature07312

- L.R. Myler, I.F. Gallardo, M.M. Soniat, R.A. Deshpande, X.B. Gonzalez, Y. Kim, T.T. Paull, and I.J. Finkelstein, "Single-Molecule Imaging Reveals How Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1 Initiates DNA Break Repair", Molecular Cell, vol. 67, pp. 891-898.e4, 2017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2017.08.002

- F. Pâques, and J.E. Haber, "Multiple pathways of recombination induced by double-strand breaks in Saccharomyces cerevisiae.", Microbiology and molecular biology reviews : MMBR, 1999. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10357855

- P. Sung, L. Krejci, S. Van Komen, and M.G. Sehorn, "Rad51 Recombinase and Recombination Mediators", Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 278, pp. 42729-42732, 2003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.R300027200

- P. Huertas, "DNA resection in eukaryotes: deciding how to fix the break", Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, vol. 17, pp. 11-16, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nsmb.1710

- N. Hustedt, and D. Durocher, "The control of DNA repair by the cell cycle", Nature Cell Biology, vol. 19, pp. 1-9, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ncb3452

- G. Ira, A. Pellicioli, A. Balijja, X. Wang, S. Fiorani, W. Carotenuto, G. Liberi, D. Bressan, L. Wan, N.M. Hollingsworth, J.E. Haber, and M. Foiani, "DNA end resection, homologous recombination and DNA damage checkpoint activation require CDK1", Nature, vol. 431, pp. 1011-1017, 2004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature02964

- Y. Aylon, B. Liefshitz, and M. Kupiec, "The CDK regulates repair of double-strand breaks by homologous recombination during the cell cycle", The EMBO Journal, vol. 23, pp. 4868-4875, 2004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.emboj.7600469

- P. Huertas, F. Cortés-Ledesma, A.A. Sartori, A. Aguilera, and S.P. Jackson, "CDK targets Sae2 to control DNA-end resection and homologous recombination", Nature, vol. 455, pp. 689-692, 2008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature07215

- X. Chen, H. Niu, W. Chung, Z. Zhu, A. Papusha, E.Y. Shim, S.E. Lee, P. Sung, and G. Ira, "Cell cycle regulation of DNA double-strand break end resection by Cdk1-dependent Dna2 phosphorylation", Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, vol. 18, pp. 1015-1019, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nsmb.2105

- M. Ferrari, D. Dibitetto, G. De Gregorio, V.V. Eapen, C.C. Rawal, F. Lazzaro, M. Tsabar, F. Marini, J.E. Haber, and A. Pellicioli, "Functional Interplay between the 53BP1-Ortholog Rad9 and the Mre11 Complex Regulates Resection, End-Tethering and Repair of a Double-Strand Break", PLoS Genetics, vol. 11, pp. e1004928, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004928

- X. Chen, H. Niu, Y. Yu, J. Wang, S. Zhu, J. Zhou, A. Papusha, D. Cui, X. Pan, Y. Kwon, P. Sung, and G. Ira, "Enrichment of Cdk1-cyclins at DNA double-strand breaks stimulates Fun30 phosphorylation and DNA end resection", Nucleic Acids Research, vol. 44, pp. 2742-2753, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv1544

- X. Yu, and J. Chen, "DNA Damage-Induced Cell Cycle Checkpoint Control Requires CtIP, a Phosphorylation-Dependent Binding Partner of BRCA1 C-Terminal Domains", Molecular and Cellular Biology, vol. 24, pp. 9478-9486, 2004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.24.21.9478-9486.2004

- L. Chen, C.J. Nievera, A.Y. Lee, and X. Wu, "Cell Cycle-dependent Complex Formation of BRCA1·CtIP·MRN Is Important for DNA Double-strand Break Repair", Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 283, pp. 7713-7720, 2008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M710245200

- M.H. Yun, and K. Hiom, "CtIP-BRCA1 modulates the choice of DNA double-strand-break repair pathway throughout the cell cycle", Nature, vol. 459, pp. 460-463, 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature07955

- K. Iwabuchi, P.L. Bartel, B. Li, R. Marraccino, and S. Fields, "Two cellular proteins that bind to wild-type but not mutant p53.", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 1994. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8016121

- M. Zimmermann, and T. de Lange, "53BP1: pro choice in DNA repair", Trends in Cell Biology, vol. 24, pp. 108-117, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tcb.2013.09.003

- T.A. Mochan, M. Venere, R.A. DiTullio, and T.D. Halazonetis, "53BP1, an activator of ATM in response to DNA damage", DNA Repair, vol. 3, pp. 945-952, 2004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.03.017

- L. Anderson, C. Henderson, and Y. Adachi, "Phosphorylation and Rapid Relocalization of 53BP1 to Nuclear Foci upon DNA Damage", Molecular and Cellular Biology, vol. 21, pp. 1719-1729, 2001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.21.5.1719-1729.2001

- I. Rappold, K. Iwabuchi, T. Date, and J. Chen, "Tumor Suppressor P53 Binding Protein 1 (53bp1) Is Involved in DNA Damage–Signaling Pathways", The Journal of Cell Biology, vol. 153, pp. 613-620, 2001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1083/jcb.153.3.613

- Z. Xia, J.C. Morales, W.G. Dunphy, and P.B. Carpenter, "Negative Cell Cycle Regulation and DNA Damage-inducible Phosphorylation of the BRCT Protein 53BP1", Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 276, pp. 2708-2718, 2001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M007665200

- A. Bothmer, D. Robbiani, M. Di Virgilio, S. Bunting, I. Klein, N. Feldhahn, J. Barlow, H. Chen, D. Bosque, E. Callen, A. Nussenzweig, and M. Nussenzweig, "Regulation of DNA End Joining, Resection, and Immunoglobulin Class Switch Recombination by 53BP1", Molecular Cell, vol. 42, pp. 319-329, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2011.03.019

- S.M. Harding, and R.G. Bristow, "Discordance between phosphorylation and recruitment of 53BP1 in response to DNA double-strand breaks", Cell Cycle, vol. 11, pp. 1432-1444, 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.4161/cc.19824

- J. Chapman, P. Barral, J. Vannier, V. Borel, M. Steger, A. Tomas-Loba, A. Sartori, I. Adams, F. Batista, and S. Boulton, "RIF1 Is Essential for 53BP1-Dependent Nonhomologous End Joining and Suppression of DNA Double-Strand Break Resection", Molecular Cell, vol. 49, pp. 858-871, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2013.01.002

- E. Callen, M. Di Virgilio, M. Kruhlak, M. Nieto-Soler, N. Wong, H. Chen, R. Faryabi, F. Polato, M. Santos, L. Starnes, D. Wesemann, J. Lee, A. Tubbs, B. Sleckman, J. Daniel, K. Ge, F. Alt, O. Fernandez-Capetillo, M. Nussenzweig, and A. Nussenzweig, "53BP1 Mediates Productive and Mutagenic DNA Repair through Distinct Phosphoprotein Interactions", Cell, vol. 153, pp. 1266-1280, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.023

- M. Di Virgilio, E. Callen, A. Yamane, W. Zhang, M. Jankovic, A.D. Gitlin, N. Feldhahn, W. Resch, T.Y. Oliveira, B.T. Chait, A. Nussenzweig, R. Casellas, D.F. Robbiani, and M.C. Nussenzweig, "Rif1 Prevents Resection of DNA Breaks and Promotes Immunoglobulin Class Switching", Science, vol. 339, pp. 711-715, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1230624

- C. Escribano-Díaz, A. Orthwein, A. Fradet-Turcotte, M. Xing, J. Young, J. Tkáč, M. Cook, A. Rosebrock, M. Munro, M. Canny, D. Xu, and D. Durocher, "A Cell Cycle-Dependent Regulatory Circuit Composed of 53BP1-RIF1 and BRCA1-CtIP Controls DNA Repair Pathway Choice", Molecular Cell, vol. 49, pp. 872-883, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2013.01.001

- M. Zimmermann, F. Lottersberger, S.B. Buonomo, A. Sfeir, and T. de Lange, "53BP1 Regulates DSB Repair Using Rif1 to Control 5′ End Resection", Science, vol. 339, pp. 700-704, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1231573

- S. Panier, and S.J. Boulton, "Double-strand break repair: 53BP1 comes into focus", Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, vol. 15, pp. 7-18, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrm3719

- H. Pei, L. Zhang, K. Luo, Y. Qin, M. Chesi, F. Fei, P.L. Bergsagel, L. Wang, Z. You, and Z. Lou, "MMSET regulates histone H4K20 methylation and 53BP1 accumulation at DNA damage sites", Nature, vol. 470, pp. 124-128, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature09658

- A. Fradet-Turcotte, M.D. Canny, C. Escribano-Díaz, A. Orthwein, C.C.Y. Leung, H. Huang, M. Landry, J. Kitevski-LeBlanc, S.M. Noordermeer, F. Sicheri, and D. Durocher, "53BP1 is a reader of the DNA-damage-induced H2A Lys 15 ubiquitin mark", Nature, vol. 499, pp. 50-54, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature12318

- M.D. Wilson, S. Benlekbir, A. Fradet-Turcotte, A. Sherker, J. Julien, A. McEwan, S.M. Noordermeer, F. Sicheri, J.L. Rubinstein, and D. Durocher, "The structural basis of modified nucleosome recognition by 53BP1", Nature, vol. 536, pp. 100-103, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature18951

- R. Baldock, M. Day, O. Wilkinson, R. Cloney, P. Jeggo, A. Oliver, F. Watts, and L. Pearl, "ATM Localization and Heterochromatin Repair Depend on Direct Interaction of the 53BP1-BRCT 2 Domain with γH2AX", Cell Reports, vol. 13, pp. 2081-2089, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2015.10.074

- G. Saredi, H. Huang, C.M. Hammond, C. Alabert, S. Bekker-Jensen, I. Forne, N. Reverón-Gómez, B.M. Foster, L. Mlejnkova, T. Bartke, P. Cejka, N. Mailand, A. Imhof, D.J. Patel, and A. Groth, "H4K20me0 marks post-replicative chromatin and recruits the TONSL–MMS22L DNA repair complex", Nature, vol. 534, pp. 714-718, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature18312

- S. Pellegrino, J. Michelena, F. Teloni, R. Imhof, and M. Altmeyer, "Replication-Coupled Dilution of H4K20me2 Guides 53BP1 to Pre-replicative Chromatin", Cell Reports, vol. 19, pp. 1819-1831, 2017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2017.05.016

- K. Acs, M.S. Luijsterburg, L. Ackermann, F.A. Salomons, T. Hoppe, and N.P. Dantuma, "The AAA-ATPase VCP/p97 promotes 53BP1 recruitment by removing L3MBTL1 from DNA double-strand breaks", Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, vol. 18, pp. 1345-1350, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nsmb.2188

- F.A. Mallette, F. Mattiroli, G. Cui, L.C. Young, M.J. Hendzel, G. Mer, T.K. Sixma, and S. Richard, "RNF8- and RNF168-dependent degradation of KDM4A/JMJD2A triggers 53BP1 recruitment to DNA damage sites", The EMBO Journal, vol. 31, pp. 1865-1878, 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/emboj.2012.47

- P. Drané, M. Brault, G. Cui, K. Meghani, S. Chaubey, A. Detappe, N. Parnandi, Y. He, X. Zheng, M.V. Botuyan, A. Kalousi, W.T. Yewdell, C. Münch, J.W. Harper, J. Chaudhuri, E. Soutoglou, G. Mer, and D. Chowdhury, "TIRR regulates 53BP1 by masking its histone methyl-lysine binding function", Nature, vol. 543, pp. 211-216, 2017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature21358

- M. Bohgaki, T. Bohgaki, S. El Ghamrasni, T. Srikumar, G. Maire, S. Panier, A. Fradet-Turcotte, G.S. Stewart, B. Raught, A. Hakem, and R. Hakem, "RNF168 ubiquitylates 53BP1 and controls its response to DNA double-strand breaks", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 110, pp. 20982-20987, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1320302111

- F. Boisvert, A. Rhie, S. Richard, and A.J. Doherty, "The GAR Motif of 53BP1 is Arginine Methylated by PRMT1 and is Necessary for 53BP1 DNA Binding Activity", Cell Cycle, vol. 4, pp. 1834-1841, 2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.4161/cc.4.12.2250

- A. Orthwein, A. Fradet-Turcotte, S.M. Noordermeer, M.D. Canny, C.M. Brun, J. Strecker, C. Escribano-Diaz, and D. Durocher, "Mitosis Inhibits DNA Double-Strand Break Repair to Guard Against Telomere Fusions", Science, vol. 344, pp. 189-193, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1248024

- D. Lee, S. Acharya, M. Kwon, P. Drane, Y. Guan, G. Adelmant, P. Kalev, J. Shah, D. Pellman, J. Marto, and D. Chowdhury, "Dephosphorylation Enables the Recruitment of 53BP1 to Double-Strand DNA Breaks", Molecular Cell, vol. 54, pp. 512-525, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2014.03.020

- X. Guo, Y. Bai, M. Zhao, M. Zhou, Q. Shen, C. Yun, H. Zhang, W. Zhu, and J. Wang, "Acetylation of 53BP1 dictates the DNA double strand break repair pathway", Nucleic Acids Research, vol. 46, pp. 689-703, 2017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkx1208

- P. Huertas, and S.P. Jackson, "Human CtIP Mediates Cell Cycle Control of DNA End Resection and Double Strand Break Repair", Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 284, pp. 9558-9565, 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M808906200

- M. Steger, O. Murina, D. Hühn, L. Ferretti, R. Walser, K. Hänggi, L. Lafranchi, C. Neugebauer, S. Paliwal, P. Janscak, B. Gerrits, G. Del Sal, O. Zerbe, and A. Sartori, "Prolyl Isomerase PIN1 Regulates DNA Double-Strand Break Repair by Counteracting DNA End Resection", Molecular Cell, vol. 50, pp. 333-343, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2013.03.023

- H. Wang, L.Z. Shi, C.C.L. Wong, X. Han, P.Y. Hwang, L.N. Truong, Q. Zhu, Z. Shao, D.J. Chen, M.W. Berns, J.R. Yates, L. Chen, and X. Wu, "The Interaction of CtIP and Nbs1 Connects CDK and ATM to Regulate HR–Mediated Double-Strand Break Repair", PLoS Genetics, vol. 9, pp. e1003277, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003277

- R.M. Densham, A.J. Garvin, H.R. Stone, J. Strachan, R.A. Baldock, M. Daza-Martin, A. Fletcher, S. Blair-Reid, J. Beesley, B. Johal, L.H. Pearl, R. Neely, N.H. Keep, F.Z. Watts, and J.R. Morris, "Human BRCA1–BARD1 ubiquitin ligase activity counteracts chromatin barriers to DNA resection", Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, vol. 23, pp. 647-655, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nsmb.3236

- H. Zhang, H. Liu, Y. Chen, X. Yang, P. Wang, T. Liu, M. Deng, B. Qin, C. Correia, S. Lee, J. Kim, M. Sparks, A.A. Nair, D.L. Evans, K.R. Kalari, P. Zhang, L. Wang, Z. You, S.H. Kaufmann, Z. Lou, and H. Pei, "A cell cycle-dependent BRCA1–UHRF1 cascade regulates DNA double-strand break repair pathway choice", Nature Communications, vol. 7, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10201

- A.V. Nimonkar, A.Z. Özsoy, J. Genschel, P. Modrich, and S.C. Kowalczykowski, "Human exonuclease 1 and BLM helicase interact to resect DNA and initiate DNA repair", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 105, pp. 16906-16911, 2008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0809380105

- N. Tomimatsu, B. Mukherjee, M. Catherine Hardebeck, M. Ilcheva, C. Vanessa Camacho, J. Louise Harris, M. Porteus, B. Llorente, K.K. Khanna, and S. Burma, "Phosphorylation of EXO1 by CDKs 1 and 2 regulates DNA end resection and repair pathway choice", Nature Communications, vol. 5, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ncomms4561

- A.V. Nimonkar, J. Genschel, E. Kinoshita, P. Polaczek, J.L. Campbell, C. Wyman, P. Modrich, and S.C. Kowalczykowski, "BLM–DNA2–RPA–MRN and EXO1–BLM–RPA–MRN constitute two DNA end resection machineries for human DNA break repair", Genes & Development, vol. 25, pp. 350-362, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gad.2003811

- J.M. Daley, T. Chiba, X. Xue, H. Niu, and P. Sung, "Multifaceted role of the Topo IIIα–RMI1-RMI2 complex and DNA2 in the BLM-dependent pathway of DNA break end resection", Nucleic Acids Research, vol. 42, pp. 11083-11091, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/gku803

- A. Sturzenegger, K. Burdova, R. Kanagaraj, M. Levikova, C. Pinto, P. Cejka, and P. Janscak, "DNA2 Cooperates with the WRN and BLM RecQ Helicases to Mediate Long-range DNA End Resection in Human Cells", Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 289, pp. 27314-27326, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M114.578823

- V. Boersma, N. Moatti, S. Segura-Bayona, M.H. Peuscher, J. van der Torre, B.A. Wevers, A. Orthwein, D. Durocher, and J.J.L. Jacobs, "MAD2L2 controls DNA repair at telomeres and DNA breaks by inhibiting 5′ end resection", Nature, vol. 521, pp. 537-540, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature14216

- M. Martina, D. Bonetti, M. Villa, G. Lucchini, and M.P. Longhese, "Saccharomyces cerevisiae Rif1 cooperates with MRX-Sae2 in promoting DNA-end resection", EMBO reports, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/embr.201338338

- F. Lazzaro, V. Sapountzi, M. Granata, A. Pellicioli, M. Vaze, J.E. Haber, P. Plevani, D. Lydall, and M. Muzi-Falconi, "Histone methyltransferase Dot1 and Rad9 inhibit single-stranded DNA accumulation at DSBs and uncapped telomeres", The EMBO Journal, 2008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/emboj.2008.81

- C. Trovesi, M. Falcettoni, G. Lucchini, M. Clerici, and M.P. Longhese, "Distinct Cdk1 Requirements during Single-Strand Annealing, Noncrossover, and Crossover Recombination", PLoS Genetics, vol. 7, pp. e1002263, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002263

- G. Ira, and A. Nussenzweig, "A new Riff: Rif1 eats its cake and has it too", EMBO reports, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/embr.201438825

- J.K. Moore, and J.E. Haber, "Cell Cycle and Genetic Requirements of Two Pathways of Nonhomologous End-Joining Repair of Double-Strand Breaks in Saccharomyces cerevisiae", Molecular and Cellular Biology, vol. 16, pp. 2164-2173, 1996. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.16.5.2164

- S.E. Lee, F. Pâques, J. Sylvan, and J.E. Haber, "Role of yeast SIR genes and mating type in directing DNA double-strand breaks to homologous and non-homologous repair paths", Current Biology, vol. 9, pp. 767-770, 1999. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0960-9822(99)80339-X