Reviews:

Microbial Cell, Vol. 3, No. 8, pp. 329 - 337; doi: 10.15698/mic2016.08.517

Functions and regulation of the MRX complex at DNA double-strand breaks

1 Dipartimento di Biotecnologie e Bioscienze, Università di Milano-Bicocca, Piazza della Scienza 2, 20126 Milan, Italy.

2 Institute of Molecular Biology gGmbH (IMB), 55128 Mainz, Germany.

Keywords: double-strand break, resection, MRX, nucleases, Tel1, Rif2, Sae2.

Abbreviations:

ADP- adenosine diphosphate,

ATM - ataxia telangiectasia mutated,

ATP - adenosine triphosphate,

Cdk - cyclin-dependent kinase,

DSB - double-strand break,

ssDNA - single-stranded DNA,

dsDNA - double-stranded DNA,

MRX - Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2,

RPA - replication protein A,

HR - homologous recombination,

NHEJ - non-homologous end joining,

SDSA - synthesis-dependent strand annealing.

Received originally: 24/03/2016 Received in revised form: 01/06/2016

Accepted: 03/06/2016

Published: 27/07/2016

Correspondence:

Maria Pia Longhese, Dipartimento di Biotecnologie e Bioscienze, Università di Milano-Bicocca, Piazza della Scienza 2, 20126 Milan, Italy mariapia.longhese@unimib.it

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Elisa Gobbini, Corinne Cassani, Matteo Villa, Diego Bonetti and Maria Pia Longhese (2016). Functions and regulation of the MRX complex at DNA double-strand breaks. Microbial Cell 3(8): 329-337.

Abstract

DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) pose a serious threat to genome stability and cell survival. Cells possess mechanisms that recognize DSBs and promote their repair through either homologous recombination (HR) or non-homologous end joining (NHEJ). The evolutionarily conserved Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2 (MRX) complex plays a central role in the cellular response to DSBs, as it is implicated in controlling end resection and in maintaining the DSB ends tethered to each other. Furthermore, it is responsible for DSB signaling by activating the checkpoint kinase Tel1 that, in turn, supports MRX function in a positive feedback loop. The present review focuses mainly on recent works in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae to highlight structure and regulation of MRX as well as its interplays with Tel1.

INTRODUCTION

DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) are cytotoxic lesions that threaten genomic integrity. Misrepair of DSBs often leads to chromosome rearrangements and loss of genetic information that can result in cell death or oncogenic transformation. DSBs can arise spontaneously in eukaryotic cells either during DNA replication or as intermediates in programmed recombination events, such as meiosis and immune system development. They can also be induced by exposure to DNA-damaging agents used in cancer therapies, including ionizing radiation and topoisomerase poisons.

–

Cells have evolved two main mechanisms to repair DSBs: non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and homologous recombination (HR). NHEJ directly religates the two broken DNA ends with no or minimal base pairing at the junction [1]. HR uses intact homologous duplex DNA sequences (sister chromatids or homologous chromosomes) as templates for repairing DSBs in an error-free manner [2][3]. In order to repair DSBs by HR, the 5’ strands of each DSB end has to be nucleolytically degraded, in a process referred to as resection [4][5]. The resulting 3’-ended single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) tails are first coated by the ssDNA binding complex Replication Protein A (RPA), which is then replaced by the recombinase Rad51 to form a right-handed helical filament that searches for DNA homologous sequences and catalyzes invasion of the duplex DNA molecules [2][3]. Initiation of resection not only channels DSB repair to HR but irreversibly inhibits NHEJ, indicating that this process is critical for discriminating between homology-dependent and end-joining repair of DSBs.

–

The highly conserved MRX/MRN complex (Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2 in yeast; Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1 in mammals) is among the first protein complexes that are recruited at DSBs [6]. MRX plays an important role in controlling end resection and in maintaining the DSB ends tethered to each other for their repair by NHEJ or HR [4][5][7]. Furthermore, it is implicated in the recruitment and activation of the protein kinase Tel1 (ATM in mammals), which plays an important role in DSB signaling [8]. Finally, MRX is essential to generate and resect meiotic DSBs, which are created by the Spo11 transesterase that forms a covalent linkage between a conserved tyrosine residue and the 5’ end of the cleaved strand [9]. Here, we review structure and regulation of the MRX complex, as well as its crosstalk with Tel1, focusing mainly on budding yeast S. cerevisiae, where the most mechanistic information is available.

ARCHITECTURE OF THE MRX COMPLEX

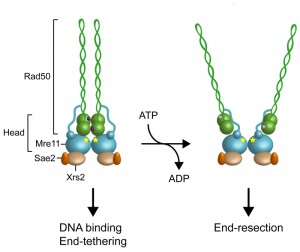

The Mre11 subunit of MRX contains five conserved phosphoesterase motifs that are essential for both 3’-5’ double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) exonuclease and ssDNA endonuclease activities [10][11][12][13][14][15][16]. Mre11 interacts with Rad50, whose domain organization is similar to that of the structural maintenance of chromosomes (SMC) family of proteins [17]. Rad50 is an ATPase belonging to the ABC ATPase superfamily that is characterized by the ATP-binding motives Walker A and B located at the amino- and carboxy-terminal regions of the protein. These motives associate together, with the intervening sequence forming a long antiparallel coiled-coil. Two Rad50 ATPase domains interact with two Mre11 nuclease proteins to form a “head” domain, which is the DNA binding and processing core of MRX [18][19][20][21][22] (Fig. 1). The Rad50 coiled-coil region protrudes from the head domain and its base interacts with two α helices of Mre11 located carboxy-terminal to the nuclease core domain [23][24][25][26]. At the apex of the coiled-coil, where the N-terminal and C-terminal regions fold back on themselves, a CXXC motif creates a zinc-mediated hook that allows dimerization between Rad50 molecules within a dimeric assembly (intra-complex) or between Rad50 molecules in separate dimeric assemblies (inter-complex). The ability of Rad50 to dimerize with Rad50 molecules that are bound to different DNA ends by Zn-dependent dimerization of the hook domains can account for the end-tethering activity of the MRX complex [27][28][29][30][31][32].

–

While Mre11 and Rad50 are conserved in bacteria and archaea, only eukaryotes possess Xrs2 (Nbs1 in mammals), which is responsible for nuclear localization of Mre11 [33]. The addition of a nuclear localization signal to Mre11 can partially suppress the hypersensitivity to DNA damaging agents of Xrs2-deficient cells [33], suggesting that localization of Mre11 into the nucleus is one of the main functions of Xrs2. Xrs2/Nbs1 contains a variety of protein-protein interaction modules, among which there is a conserved region within the C-terminus that is responsible for the interaction with Tel1/ATM [34][35].

FUNCTIONAL DYNAMICS OF THE MRX COMPLEX

The MRX complex plays a central role in signaling, processing and repairing of DSBs. Structural studies have shown that these diverse functions are regulated by the ATP binding and hydrolysis activity of Rad50 that induce conformational changes of both Rad50 and Mre11. In the presence of ATP, Mre11 and Rad50 adopt a “closed” conformation, in which Rad50 head domains dimerize and occlude the nuclease active site of Mre11 (Fig. 1) [24][26]. ATP hydrolysis drives the rotation of the two nucleotide binding domains of Rad50, leading to disengagement of the Rad50 dimer and DNA melting, so that the Mre11 active sites can access DNA to initiate DSB resection [23][36] (Fig. 1). Point mutations that stabilize the ATP-bound conformation of Rad50 result in both reduced Mre11 nuclease activity and increased DNA binding and end-tethering [37]. By contrast, mutations that increase ATP hydrolysis enhance both Mre11 nuclease and end-resection activities [37]. These data suggest that the ATP-bound state is required for DNA binding and tethering, whereas release from the ATP-bound state by ATP hydrolysis is necessary to allow access to DNA of the Mre11 nuclease active site and subsequent DSB resection (Fig. 1).

–

Rad50 has a slow ATP hydrolysis rate [38], suggesting that either MRX exists mostly in the ATP-bound state or other proteins can promote ATP hydrolysis within the cell. In S. cerevisiae, MRX is known to interact with Rif2, which is recruited to telomeric DNA ends by Rap1 and negatively regulates telomerase action [39][40][41][42]. Rif2 was recently found to be recruited also to intrachromosomal DSBs in a manner partially dependent on MRX [43]. Interestingly, Rif2 enhances the ATP hydrolysis activity of the MRX complex [43]. Furthermore, rif2∆ cells show an increased efficiency of both end-tethering and NHEJ compared to wild type cells, indicating that Rif2 counteracts end-tethering and DSB repair by NHEJ [43]. These observations suggest that Rif2 can modulate the choice between HR and NHEJ by promoting the transition of the MRX complex from a closed state, required for tethering, to an open state that is competent for DSB resection. Interestingly, Rif2 is known to counteract NHEJ at telomeres [44]. Whether this Rif2 function depends on a Rif2-mediated regulation of MRX conformational changes is an interesting question that remains to be addressed.

MRX IN END-RESECTION

The first step in HR is the degradation of the 5’ DNA strands on either side of the DSB through a process termed resection [4][5]. Several lines of evidence indicate that the MRX complex functions together with the Sae2 protein (CtIP in mammals) in the processing of the DSB ends. In fact, S. cerevisiae mutants lacking Sae2 or any component of the MRX/MRN complex delay resection of an endonuclease-induced DSB by acting in the same epistasis group [45][46][47] [48]. Furthermore, both Sae2 and MRX play a unique role in the processing of hairpin-containing DNA structures [49][50][51]. Finally, sae2∆, mre11 nuclease defective mutants and a class of separation-of-function rad50 and mre11 alleles, named rad50s and mre11s, allow formation of meiotic DSBs but prevent their resection [11][52][53][54][55][56].

–

However, Mre11 has a 3’-5’ dsDNA exonuclease activity, whose polarity is opposite to that required to generate the 3’-ended ssDNA at the DSB ends [12][13]. Mre11 possesses also a weak endonuclease activity on 5’-terminated dsDNA strands [16][57][58], which is strongly stimulated by Sae2 and by a protein block at the DNA ends [59]. Furthermore, sae2∆ and mre11 nuclease mutants are defective in the removal of covalent adducts, such as Spo11 (the transesterase that generates meiotic DSBs and remains covalently bound to the 5’ strands of the ensuing breaks) [60][61][62][63] or hairpin-containing DNA structures, from DNA ends [49][50][51]. The same mutants are also hypersensitive to both camptothecin, which extends the half-life of DNA-topoisomerase cleavage complexes, and ionizing radiations, which can generate chemically complex DSBs [64][65][66]. Altogether, these observations suggest that the MRX complex initiates DNA resection by creating a nick that provides an internal entry site for nucleases capable of degrading DNA in a 5’-3’ direction (Fig. 2).

–

These nucleases comprise the 5’-3’ exonucleases Exo1 and the endonuclease Dna2, which control two partially overlapping pathways [67][68]. While Exo1 is able to release mononucleotide products from a dsDNA end [69][70][71], Dna2-mediated resection needs the RecQ helicase Sgs1 (BLM in humans) that unwinds double-stranded DNA in a 3’-5’ polarity [72][73][74]. Noteworthy, the MRX complex not only provides an entry site for Dna2 and Exo1, but it has also a structural role in allowing their recruitment to the DSB [75], thus explaining why mre11∆ cells show a resection defect more severe than sae2∆ or mre11 nuclease defective mutants. In any case, mre11∆ cells are severely defective in DSB resection when the break is present in the G2 phase of the cell cycle, whereas they slow down resection only of two fold when the break occurs when they are exponentially growing [45][46][47][48]. This observation, together with the finding that a DSB is processed more efficiently during S phase than in G2 [76], suggests that ongoing DNA replication can partially bypass MRX requirement in DSB resection.

–

Both Sae2 and Dna2 have been shown to be targets of cyclin-dependent kinase (Cdk1 in yeast)-Clb complexes [77][78], which allow DSB resection to take place only during the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle when sister chromatids or homologous chromosomes are present as repair templates [79][80]. Substitution of Sae2 S267 with a nonphosphorylatable residue impairs DSB processing, whereas the same process takes place when Sae2 S267 is replaced by a residue mimicking constitutive phosphorylation [77]. Similarly, substitution of three Cdk1 consensus sites of Dna2 with alanines reduces extensive resection [78]. Notably, the lack of any subunit of the Ku complex allows DSB resection in G1-arrested cells when Cdk1-Clb activity is low [76][81], suggesting that Cdk1-Clb activity can relieve the inhibitory effect exerted by Ku on Sae2. The finding that this resection in G1-arrested Ku-deficient cells is limited to the break-proximal sequence [76][81] indicates that Cdk1 is still required to activate proteins involved in extensive DSB resection such as Dna2.

–

Altogether, these data support a model, where MRX is recruited to the DSB ends in the ATP-bound state. In this configuration, MRX maintains the DSB ends tethered to each other to allow DSB repair by NHEJ (Fig. 2). Upon ATP hydrolysis by Rad50 and Cdk1-mediated phosphorylation events, MRX and Sae2 provide an initial incision of the 5’ strand at a certain distance from the DSB end. As first proposed by Garcia et al. [82], this initial cleavage is followed by bidirectional resection using the Mre11 3’-5’ exonuclease and the 5’-3’ nuclease activities of Exo1 or Dna2-Sgs1 (Fig. 2).

ACTIVATION OF Tel1 BY MRX

In addition to promoting end-resection and to maintaining the DSB ends tethered to each other, MRX/MRN is required to activate Tel1, which is a member of the evolutionary conserved phosphoinositide 3-kinase-related protein kinase (PIKK) family and whose mammalian ortholog is called ATM (Ataxia Telangiectasia Mutated) [8]. The PIKK enzymes are large serine/threonine protein kinases characterized by N-terminal HEAT repeat domains and by C-terminal kinase domains [83]. The C-terminal kinase domain of ATM is flanked by two regions called FAT (FRAP, ATM, TRRAP) and FATC (FAT C-terminus), which both participate in the regulation of the kinase activity [84].

–

Tel1/ATM is a master regulator of the DNA damage response in both yeast and mammals, where it coordinates checkpoint activation and DNA repair in response to DNA DSBs and oxidative stress [85][86]. Biallelic mutations in ATM result in ataxia telangiectasia (AT), an autosomal recessive inherited disease characterized by cerebellar degeneration, strong predisposition to malignancy, growth retardation, radiosensitivity, immune deficiencies, and premature aging [87][88][89]. The functional interaction between MRX/MRN and Tel1/ATM is supported by the finding that biallelic mutation in the MRE11 gene causes a genetic syndrome, called ataxia-telangiectasia-like disease (ATLD), whose clinical phenotypes are nearly indistinguishable from AT [90][91]. ATLD cells exhibit reduced activation of ATM by DSBs, suggesting that MRN is required for optimal ATM activation following DSB induction, thus explaining the AT-like phenotype of ATLD patients.

–

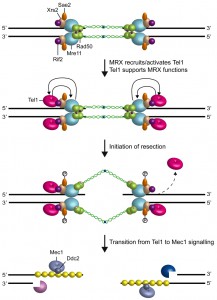

Subsequent studies have revealed that MRX/MRN drives the localization of Tel1/ATM to the site of damage through direct interaction between Tel1/ATM with Xrs2/Nbs1 [35][92][93][94] (Fig. 3). The Tel1 kinase activity is stimulated by MRX binding to DNA-protein complexes at DSBs [95] and the purified MRX/MRN complex increases the catalytic activity of Tel1/ATM in the presence of DNA fragments [96][97][98], suggesting that MRX/MRN also controls Tel1/ATM catalytic activity through an unknown mechanism.

–

Tel1 was originally identified in S. cerevisiae by screen for genes involved in telomere length maintenance [99][100][101]. In addition to its role in DSB repair, Tel1 is required to maintain telomere length by promoting telomerase recruitment through phosphorylation events [102]. Deletion of any subunit of the MRX complex causes telomere shortening similar to that caused by the lack of Tel1 or both Tel1 and Rad50, indicating that Tel1 acts in the same pathway of MRX in telomere length maintenance [103]. As it is observed at DSBs, Tel1 binding to telomeres is dependent on an interaction between Tel1 and the carboxyl terminus of the Xrs2 subunit of the MRX complex [104][105]. Tel1 association to telomeres is counteracted by Rif2, which is known to inhibit telomerase-dependent telomere elongation [39][40]. Co-immunoprecipitation experiments show that the C terminus of Xrs2 interacts with Rif2 [41]. As Tel1 also binds this Xrs2 region [41], Rif2 may reduce Tel1 association to telomeres by interfering with MRX-Tel1 interaction. Further support for a Tel1-Rif2 competition comes from the recent finding that a hypermorphic allele of TEL1 (TEL1-hy909) is capable to overcome the inhibitory activity of Rif2 on MRX [42]. The Rif2 function in modulating MRX-Tel1 interaction is not restricted to telomeres. In fact, the lack of Rif2 increases the association of MRX also to intrachromosomal DNA ends in a Tel1-dependent manner [43] (Fig. 3). Consistent with a direct role of this protein at DSBs, Rif2 can bind DNA ends both in vitro and in vivo [43], although the amount of Rif2 bound at a DSB flanked by telomeric repeats is higher than that found at a DSB that does not contain telomeric sequences [41][42][43].

–

In S. cerevisiae, Tel1 signaling activity is disrupted when the DSB ends are subjected to 5’-3’ exonucleolytic degradation [106] (Fig. 3). Similarly, ATM activation in mammals is triggered by blunt ends or short overhangs and is inhibited by long overhangs of 3’ or 5’ ssDNA [107]. Interestingly, the lack of either Sae2 or Mre11 nuclease activity enhances Tel1/ATM activation at DSBs by increasing MRX persistence at DSBs [47][108], suggesting that Sae2 and Mre11 nuclease can inhibit Tel1/ATM signaling activity. As the mammalian counterpart of MRX has been shown to bind ssDNA-dsDNA junctions [109], the slowing down of DSB resection might lead to MRX persistence at DSBs by increasing the stability of these DNA structures. Alternatively, ssDNA near the dsDNA junction may break to form a second DSB that activates MRX-Tel1, as suggested in [110].

–

Attenuation of Tel1/ATM signaling by nuclease-mediated DSB resection is accompanied by activation of the checkpoint kinase Mec1 (ATR in mammals), which is another member of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase-related protein kinase family [8] (Fig. 3). In both yeast and mammals, all Mec1/ATR functions at DSBs depend on the interaction with Ddc2 (ATRIP in mammals), which mediates Mec1/ATR recruitment on RPA-coated ssDNA 3’ overhangs [111][112][113][114].

REGULATION OF MRX BY Tel1

Recent data have shown that Tel1, once recruited to DSBs by MRX, supports MRX function in a positive feedback loop (Fig. 3). In fact, a screen for S. cerevisiae mutants that require Tel1 to survive to genotoxic treatments recently showed that a mutation in Rad50 (rad50-V1269M) makes tel1∆ cells hypersensitive to DNA damaging agents [43]. The rad50-V1269M mutation impairs MRX association at DSBs that is further reduced by the lack of Tel1, indicating that Tel1 promotes/stabilizes MRX association to the DSB. Interestingly, Tel1 exerts this function independently of its kinase activity [43], suggesting that it plays a structural role in promoting/stabilizing MRX retention to DSBs. Similarly, the lack of Tel1, but not of its kinase activity, was shown to impair MRX association also at DNA ends flanked by telomeric DNA repeats [43].

–

Although the rad50-V1269M mutation resides in the globular domain of Rad50, rad50-V1269M tel1∆ cells are severely defective in the maintenance of the DSB ends tethered to each other [43], suggesting that the Rad50 hook and globular domains function interdependently. Consistent with this hypothesis, it has been shown that proper association to DNA of the globular domain can induce parallel orientation of the Rad50 coiled-coil domains that favours intercomplex association needed for DNA tethering [22]. Furthermore, mutations in the hook domain that reduce its dimerization state affect the MRX functions specified by the globular domain, including Tel1/ATM activation, Rad50-Mre11 interaction, NHEJ and DSB resection [115]. Altogether these results support a model wherein Tel1, once loaded at DSBs by MRX, exerts a positive feedback by promoting an end-specific association of MRX with DNA (Fig. 3). This Tel1-mediated regulation of DNA-MRX retention is important to allow the establishment of a productive MRX intercomplex association that is needed to maintain DNA ends in close proximity.

–

Defects in maintaining the DSB ends tethered to each other in tel1∆ rad50-V1269M cells affect DSB repair not only by NHEJ, but also by HR [43]. During HR, the 5’ ends at the DSB are degraded to yield 3’ ssDNA tails that invade an intact homologous duplex DNA to prime DNA synthesis. After ligation of the newly synthesized DNA to the resected 5’ strands, a double Holliday junction intermediate is generated and can be resolved by endonucleolytic cleavage to produce non-crossover (NCO) or crossover (CO) products. However, in mitotic cells, the invading strand is often displaced after limited synthesis and anneals to the 3’ ssDNA tail at the other end of the DSB. After fill-in synthesis and ligation, this mechanism, called synthesis-dependent strand annealing (SDSA), generates exclusively NCO products and explain the lower incidence of associated COs during mitotic DSB repair [116][117][118]. Interestingly, tel1∆ rad50-V1269M cells are specifically impaired in SDSA [43], suggesting that the tethering activity exerted by MRX can be particularly important to promote the annealing of the displaced strand to the 3’ ssDNA tail at the other end of the DSB. By contrast, this function can be escaped when the second DSB end is already captured by the D-loop and the DNA intermediate is stabilized by the formation of a double Holliday junction.

CONCLUSION

Overall, the MRX complex emerges as a multifunctional enzyme involved in a number of activities that include sensing and processing of the DSB ends. Furthermore, its association with Tel1 links DSB sensing with signaling by the checkpoint machinery to coordinate DSB repair with cell cycle progression. These functions are regulated by ATP binding and hydrolysis activities of Rad50 that provide intrinsic dynamics and flexibility properties. Furthermore, the Tel1 protein itself, once recruited at DNA ends by MRX, supports the end-tethering activity of the MRX complex by facilitating its proper association to DNA ends. These observations reveal the complex architecture that characterizes the activity of MRX and Tel1 in DNA-damage response, maintenance of genetic stability and cell cycle regulation.

References

- K.K. Chiruvella, Z. Liang, and T.E. Wilson, "Repair of Double-Strand Breaks by End Joining", Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, vol. 5, pp. a012757-a012757, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a012757

- J. San Filippo, P. Sung, and H. Klein, "Mechanism of Eukaryotic Homologous Recombination", Annual Review of Biochemistry, vol. 77, pp. 229-257, 2008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.061306.125255

- A. Mehta, and J.E. Haber, "Sources of DNA Double-Strand Breaks and Models of Recombinational DNA Repair", Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, vol. 6, pp. a016428-a016428, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a016428

- M.P. Longhese, D. Bonetti, N. Manfrini, and M. Clerici, "Mechanisms and regulation of DNA end resection", The EMBO Journal, vol. 29, pp. 2864-2874, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/emboj.2010.165

- L.S. Symington, "End Resection at Double-Strand Breaks: Mechanism and Regulation", Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, vol. 6, pp. a016436-a016436, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a016436

- M. Lisby, J.H. Barlow, R.C. Burgess, and R. Rothstein, "Choreography of the DNA Damage Response", Cell, vol. 118, pp. 699-713, 2004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.015

- T.H. Stracker, and J.H.J. Petrini, "The MRE11 complex: starting from the ends", Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, vol. 12, pp. 90-103, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrm3047

- E. Gobbini, D. Cesena, A. Galbiati, A. Lockhart, and M.P. Longhese, "Interplays between ATM/Tel1 and ATR/Mec1 in sensing and signaling DNA double-strand breaks", DNA Repair, vol. 12, pp. 791-799, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.dnarep.2013.07.009

- I. Lam, and S. Keeney, "Mechanism and Regulation of Meiotic Recombination Initiation", Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, vol. 7, pp. a016634, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a016634

- D.A. Bressan, H.A. Olivares, B.E. Nelms, and J.H. Petrini, "Alteration of N-terminal phosphoesterase signature motifs inactivates Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mre11.", Genetics, 1998. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9755192

- M. Furuse, Y. Nagase, H. Tsubouchi, K. Murakami-Murofushi, T. Shibata, and K. Ohta, "Distinct roles of two separablein vitroactivities of yeast Mre11 in mitotic and meiotic recombination", The EMBO Journal, vol. 17, pp. 6412-6425, 1998. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/emboj/17.21.6412

- T.T. Paull, and M. Gellert, "The 3′ to 5′ Exonuclease Activity of Mre11 Facilitates Repair of DNA Double-Strand Breaks", Molecular Cell, vol. 1, pp. 969-979, 1998. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80097-0

- K.M. Trujillo, S.F. Yuan, E.Y.P. Lee, and P. Sung, "Nuclease Activities in a Complex of Human Recombination and DNA Repair Factors Rad50, Mre11, and p95", Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 273, pp. 21447-21450, 1998. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.273.34.21447

- T. Usui, T. Ohta, H. Oshiumi, J. Tomizawa, H. Ogawa, and T. Ogawa, "Complex Formation and Functional Versatility of Mre11 of Budding Yeast in Recombination", Cell, vol. 95, pp. 705-716, 1998. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81640-2

- S. Moreau, J.R. Ferguson, and L.S. Symington, "The Nuclease Activity of Mre11 Is Required for Meiosis but Not for Mating Type Switching, End Joining, or Telomere Maintenance", Molecular and Cellular Biology, vol. 19, pp. 556-566, 1999. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.19.1.556

- K.M. Trujillo, and P. Sung, "DNA Structure-specific Nuclease Activities in theSaccharomyces cerevisiae Rad50·Mre11 Complex", Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 276, pp. 35458-35464, 2001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M105482200

- K. Hopfner, A. Karcher, D.S. Shin, L. Craig, L. Arthur, J.P. Carney, and J.A. Tainer, "Structural Biology of Rad50 ATPase", Cell, vol. 101, pp. 789-800, 2000. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80890-9

- M. de Jager, J. van Noort, D.C. van Gent, C. Dekker, R. Kanaar, and C. Wyman, "Human Rad50/Mre11 is a flexible complex that can tether DNA ends.", Molecular cell, 2001. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11741547

- K.P. Hopfner, A. Karcher, L. Craig, T.T. Woo, J.P. Carney, and J.A. Tainer, "Structural biochemistry and interaction architecture of the DNA double-strand break repair Mre11 nuclease and Rad50-ATPase.", Cell, 2001. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11371344

- K. Hopfner, L. Craig, G. Moncalian, R.A. Zinkel, T. Usui, B.A.L. Owen, A. Karcher, B. Henderson, J. Bodmer, C.T. McMurray, J.P. Carney, J.H.J. Petrini, and J.A. Tainer, "The Rad50 zinc-hook is a structure joining Mre11 complexes in DNA recombination and repair", Nature, vol. 418, pp. 562-566, 2002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature00922

- G. Moncalian, B. Lengsfeld, V. Bhaskara, K. Hopfner, A. Karcher, E. Alden, J.A. Tainer, and T.T. Paull, "The Rad50 Signature Motif: Essential to ATP Binding and Biological Function", Journal of Molecular Biology, vol. 335, pp. 937-951, 2004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2003.11.026

- F. Moreno-Herrero, M. de Jager, N.H. Dekker, R. Kanaar, C. Wyman, and C. Dekker, "Mesoscale conformational changes in the DNA-repair complex Rad50/Mre11/Nbs1 upon binding DNA", Nature, vol. 437, pp. 440-443, 2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature03927

- K. Lammens, D. Bemeleit, C. Möckel, E. Clausing, A. Schele, S. Hartung, C. Schiller, M. Lucas, C. Angermüller, J. Söding, K. Sträßer, and K. Hopfner, "The Mre11:Rad50 Structure Shows an ATP-Dependent Molecular Clamp in DNA Double-Strand Break Repair", Cell, vol. 145, pp. 54-66, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.038

- H.S. Lim, J.S. Kim, Y.B. Park, G.H. Gwon, and Y. Cho, "Crystal structure of the Mre11–Rad50–ATPγS complex: understanding the interplay between Mre11 and Rad50", Genes & Development, vol. 25, pp. 1091-1104, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gad.2037811

- G.J. Williams, R.S. Williams, J.S. Williams, G. Moncalian, A.S. Arvai, O. Limbo, G. Guenther, S. SilDas, M. Hammel, P. Russell, and J.A. Tainer, "ABC ATPase signature helices in Rad50 link nucleotide state to Mre11 interface for DNA repair", Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, vol. 18, pp. 423-431, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nsmb.2038

- C. Möckel, K. Lammens, A. Schele, and K. Hopfner, "ATP driven structural changes of the bacterial Mre11:Rad50 catalytic head complex", Nucleic Acids Research, vol. 40, pp. 914-927, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkr749

- D.A. Bressan, B.K. Baxter, and J.H.J. Petrini, "The Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2 Protein Complex Facilitates Homologous Recombination-Based Double-Strand Break Repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae", Molecular and Cellular Biology, vol. 19, pp. 7681-7687, 1999. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.19.11.7681

- L. Chen, K. Trujillo, W. Ramos, P. Sung, and A.E. Tomkinson, "Promotion of Dnl4-Catalyzed DNA End-Joining by the Rad50/Mre11/Xrs2 and Hdf1/Hdf2 Complexes", Molecular Cell, vol. 8, pp. 1105-1115, 2001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00388-4

- K. Lobachev, E. Vitriol, J. Stemple, M.A. Resnick, and K. Bloom, "Chromosome Fragmentation after Induction of a Double-Strand Break Is an Active Process Prevented by the RMX Repair Complex", Current Biology, vol. 14, pp. 2107-2112, 2004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2004.11.051

- J.J.W. Wiltzius, M. Hohl, J.C. Fleming, and J.H.J. Petrini, "The Rad50 hook domain is a critical determinant of Mre11 complex functions", Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, vol. 12, pp. 403-407, 2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nsmb928

- M. Hohl, Y. Kwon, S.M. Galván, X. Xue, C. Tous, A. Aguilera, P. Sung, and J.H.J. Petrini, "The Rad50 coiled-coil domain is indispensable for Mre11 complex functions", Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, vol. 18, pp. 1124-1131, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nsmb.2116

-

F.U. Seifert, K. Lammens, G. Stoehr, B. Kessler, and K. Hopfner, "Structural mechanism of

ATP ‐dependentDNA binding andDNA end bridging by eukaryotic Rad50", The EMBO Journal, vol. 35, pp. 759-772, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.15252/embj.201592934 - Y. Tsukamoto, C. Mitsuoka, M. Terasawa, H. Ogawa, and T. Ogawa, "Xrs2p Regulates Mre11p Translocation to the Nucleus and Plays a Role in Telomere Elongation and Meiotic Recombination", Molecular Biology of the Cell, vol. 16, pp. 597-608, 2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1091/mbc.E04-09-0782

- J. Lloyd, J.R. Chapman, J.A. Clapperton, L.F. Haire, E. Hartsuiker, J. Li, A.M. Carr, S.P. Jackson, and S.J. Smerdon, "A Supramodular FHA/BRCT-Repeat Architecture Mediates Nbs1 Adaptor Function in Response to DNA Damage", Cell, vol. 139, pp. 100-111, 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.043

- D. Nakada, K. Matsumoto, and K. Sugimoto, "ATM-related Tel1 associates with double-strand breaks through an Xrs2-dependent mechanism", Genes & Development, vol. 17, pp. 1957-1962, 2003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gad.1099003

-

Y. Liu, S. Sung, Y. Kim, F. Li, G. Gwon, A. Jo, A. Kim, T. Kim, O. Song, S.E. Lee, and Y. Cho, "

ATP ‐dependentDNA binding, unwinding, and resection by the Mre11/Rad50 complex", The EMBO Journal, vol. 35, pp. 743-758, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.15252/embj.201592462 - R.A. Deshpande, G.J. Williams, O. Limbo, R.S. Williams, J. Kuhnlein, J. Lee, S. Classen, G. Guenther, P. Russell, J.A. Tainer, and T.T. Paull, "ATP-driven Rad50 conformations regulate DNA tethering, end resection, and ATM checkpoint signaling", The EMBO Journal, vol. 33, pp. 482-500, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/embj.201386100

- J. Majka, B. Alford, J. Ausio, R.M. Finn, and C.T. McMurray, "ATP Hydrolysis by RAD50 Protein Switches MRE11 Enzyme from Endonuclease to Exonuclease", Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 287, pp. 2328-2341, 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M111.307041

- D. Wotton, and D. Shore, "A novel Rap1p-interacting factor, Rif2p, cooperates with Rif1p to regulate telomere length in Saccharomyces cerevisiae.", Genes & Development, vol. 11, pp. 748-760, 1997. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gad.11.6.748

- D.L. Levy, and E.H. Blackburn, "Counting of Rif1p and Rif2p on Saccharomyces cerevisiae Telomeres Regulates Telomere Length", Molecular and Cellular Biology, vol. 24, pp. 10857-10867, 2004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.24.24.10857-10867.2004

- Y. Hirano, K. Fukunaga, and K. Sugimoto, "Rif1 and Rif2 Inhibit Localization of Tel1 to DNA Ends", Molecular Cell, vol. 33, pp. 312-322, 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2008.12.027

- M. Martina, M. Clerici, V. Baldo, D. Bonetti, G. Lucchini, and M.P. Longhese, "A Balance between Tel1 and Rif2 Activities Regulates Nucleolytic Processing and Elongation at Telomeres", Molecular and Cellular Biology, vol. 32, pp. 1604-1617, 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.06547-11

- C. Cassani, E. Gobbini, W. Wang, H. Niu, M. Clerici, P. Sung, and M.P. Longhese, "Tel1 and Rif2 Regulate MRX Functions in End-Tethering and Repair of DNA Double-Strand Breaks", PLOS Biology, vol. 14, pp. e1002387, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1002387

- S. Marcand, B. Pardo, A. Gratias, S. Cahun, and I. Callebaut, "Multiple pathways inhibit NHEJ at telomeres", Genes & Development, vol. 22, pp. 1153-1158, 2008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gad.455108

- E.L. Ivanov, N. Sugawara, C.I. White, F. Fabre, and J.E. Haber, "Mutations in XRS2 and RAD50 delay but do not prevent mating-type switching in Saccharomyces cerevisiae.", Molecular and Cellular Biology, vol. 14, pp. 3414-3425, 1994. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.14.5.3414

- M. Clerici, D. Mantiero, G. Lucchini, and M.P. Longhese, "The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Sae2 Protein Promotes Resection and Bridging of Double Strand Break Ends", Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 280, pp. 38631-38638, 2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M508339200

- M. Clerici, D. Mantiero, G. Lucchini, and M.P. Longhese, "The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Sae2 protein negatively regulates DNA damage checkpoint signalling", EMBO reports, vol. 7, pp. 212-218, 2006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.embor.7400593

- S. Moreau, E.A. Morgan, and L.S. Symington, "Overlapping functions of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mre11, Exo1 and Rad27 nucleases in DNA metabolism.", Genetics, 2001. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11779786

- K.S. Lobachev, D.A. Gordenin, and M.A. Resnick, "The Mre11 Complex Is Required for Repair of Hairpin-Capped Double-Strand Breaks and Prevention of Chromosome Rearrangements", Cell, vol. 108, pp. 183-193, 2002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00614-1

- J. Yu, K. Marshall, M. Yamaguchi, J.E. Haber, and C.F. Weil, "Microhomology-Dependent End Joining and Repair of Transposon-Induced DNA Hairpins by Host Factors in Saccharomyces cerevisiae", Molecular and Cellular Biology, vol. 24, pp. 1351-1364, 2004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.24.3.1351-1364.2004

- A.J. Rattray, B.K. Shafer, B. Neelam, and J.N. Strathern, "A mechanism of palindromic gene amplification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae", Genes & Development, vol. 19, pp. 1390-1399, 2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gad.1315805

- L. Cao, E. Alani, and N. Kleckner, "A pathway for generation and processing of double-strand breaks during meiotic recombination in S. cerevisiae", Cell, vol. 61, pp. 1089-1101, 1990. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0092-8674(90)90072-M

- E. Alani, R. Padmore, and N. Kleckner, "Analysis of wild-type and rad50 mutants of yeast suggests an intimate relationship between meiotic chromosome synapsis and recombination", Cell, vol. 61, pp. 419-436, 1990. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0092-8674(90)90524-I

- K. Nairz, and F. Klein, "mre11S—a yeast mutation that blocks double-strand-break processing and permits nonhomologous synapsis in meiosis", Genes & Development, vol. 11, pp. 2272-2290, 1997. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gad.11.17.2272

- S. Prinz, A. Amon, and F. Klein, "Isolation of COM1, a new gene required to complete meiotic double-strand break-induced recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae.", Genetics, 1997. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9215887

- H. Tsubouchi, and H. Ogawa, "A Novel mre11 Mutation Impairs Processing of Double-Strand Breaks of DNA during Both Mitosis and Meiosis", Molecular and Cellular Biology, vol. 18, pp. 260-268, 1998. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.18.1.260

- B.B. Hopkins, and T.T. Paull, "The P. furiosus Mre11/Rad50 Complex Promotes 5′ Strand Resection at a DNA Double-Strand Break", Cell, vol. 135, pp. 250-260, 2008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.054

- R.S. Williams, G. Moncalian, J.S. Williams, Y. Yamada, O. Limbo, D.S. Shin, L.M. Groocock, D. Cahill, C. Hitomi, G. Guenther, D. Moiani, J.P. Carney, P. Russell, and J.A. Tainer, "Mre11 Dimers Coordinate DNA End Bridging and Nuclease Processing in Double-Strand-Break Repair", Cell, vol. 135, pp. 97-109, 2008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.017

- E. Cannavo, and P. Cejka, "Sae2 promotes dsDNA endonuclease activity within Mre11–Rad50–Xrs2 to resect DNA breaks", Nature, vol. 514, pp. 122-125, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature13771

- S. Keeney, and N. Kleckner, "Covalent protein-DNA complexes at the 5' strand termini of meiosis-specific double-strand breaks in yeast.", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 92, pp. 11274-11278, 1995. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.92.24.11274

- M.J. Neale, J. Pan, and S. Keeney, "Endonucleolytic processing of covalent protein-linked DNA double-strand breaks", Nature, vol. 436, pp. 1053-1057, 2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature03872

- E. Hartsuiker, K. Mizuno, M. Molnar, J. Kohli, K. Ohta, and A.M. Carr, "Ctp1CtIP and Rad32Mre11 Nuclease Activity Are Required for Rec12Spo11 Removal, but Rec12Spo11 Removal Is Dispensable for Other MRN-Dependent Meiotic Functions", Molecular and Cellular Biology, vol. 29, pp. 1671-1681, 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.01182-08

- N. Milman, E. Higuchi, and G.R. Smith, "Meiotic DNA Double-Strand Break Repair Requires Two Nucleases, MRN and Ctp1, To Produce a Single Size Class of Rec12 (Spo11)-Oligonucleotide Complexes", Molecular and Cellular Biology, vol. 29, pp. 5998-6005, 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.01127-09

- E. Hartsuiker, M.J. Neale, and A.M. Carr, "Distinct Requirements for the Rad32Mre11 Nuclease and Ctp1CtIP in the Removal of Covalently Bound Topoisomerase I and II from DNA", Molecular Cell, vol. 33, pp. 117-123, 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2008.11.021

- W.D. Henner, S.M. Grunberg, and W.A. Haseltine, "Enzyme action at 3' termini of ionizing radiation-induced DNA strand breaks.", The Journal of biological chemistry, 1983. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6361028

- S. Barker, M. Weinfeld, J. Zheng, L. Li, and D. Murray, "Identification of Mammalian Proteins Cross-linked to DNA by Ionizing Radiation", Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 280, pp. 33826-33838, 2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M502477200

- E.P. Mimitou, and L.S. Symington, "Sae2, Exo1 and Sgs1 collaborate in DNA double-strand break processing", Nature, vol. 455, pp. 770-774, 2008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature07312

- Z. Zhu, W. Chung, E.Y. Shim, S.E. Lee, and G. Ira, "Sgs1 Helicase and Two Nucleases Dna2 and Exo1 Resect DNA Double-Strand Break Ends", Cell, vol. 134, pp. 981-994, 2008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.037

- B. Lee, and D.M. Wilson, "The RAD2 Domain of Human Exonuclease 1 Exhibits 5′ to 3′ Exonuclease and Flap Structure-specific Endonuclease Activities", Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 274, pp. 37763-37769, 1999. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.274.53.37763

- P.T. Tran, N. Erdeniz, S. Dudley, and R. Liskay, "Characterization of nuclease-dependent functions of Exo1p in Saccharomyces cerevisiae", DNA Repair, vol. 1, pp. 895-912, 2002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1568-7864(02)00114-3

- E. Cannavo, P. Cejka, and S.C. Kowalczykowski, "Relationship of DNA degradation by Saccharomyces cerevisiae Exonuclease 1 and its stimulation by RPA and Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2 to DNA end resection", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 110, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1305166110

- P. Cejka, E. Cannavo, P. Polaczek, T. Masuda-Sasa, S. Pokharel, J.L. Campbell, and S.C. Kowalczykowski, "DNA end resection by Dna2–Sgs1–RPA and its stimulation by Top3–Rmi1 and Mre11–Rad50–Xrs2", Nature, vol. 467, pp. 112-116, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature09355

- H. Niu, W. Chung, Z. Zhu, Y. Kwon, W. Zhao, P. Chi, R. Prakash, C. Seong, D. Liu, L. Lu, G. Ira, and P. Sung, "Mechanism of the ATP-dependent DNA end-resection machinery from Saccharomyces cerevisiae", Nature, vol. 467, pp. 108-111, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature09318

- A.V. Nimonkar, J. Genschel, E. Kinoshita, P. Polaczek, J.L. Campbell, C. Wyman, P. Modrich, and S.C. Kowalczykowski, "BLM–DNA2–RPA–MRN and EXO1–BLM–RPA–MRN constitute two DNA end resection machineries for human DNA break repair", Genes & Development, vol. 25, pp. 350-362, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gad.2003811

- E.Y. Shim, W. Chung, M.L. Nicolette, Y. Zhang, M. Davis, Z. Zhu, T.T. Paull, G. Ira, and S.E. Lee, "Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mre11/Rad50/Xrs2 and Ku proteins regulate association of Exo1 and Dna2 with DNA breaks", The EMBO Journal, vol. 29, pp. 3370-3380, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/emboj.2010.219

- C. Zierhut, and J.F.X. Diffley, "Break dosage, cell cycle stage and DNA replication influence DNA double strand break response", The EMBO Journal, vol. 27, pp. 1875-1885, 2008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/emboj.2008.111

- P. Huertas, F. Cortés-Ledesma, A.A. Sartori, A. Aguilera, and S.P. Jackson, "CDK targets Sae2 to control DNA-end resection and homologous recombination", Nature, vol. 455, pp. 689-692, 2008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature07215

- X. Chen, H. Niu, W. Chung, Z. Zhu, A. Papusha, E.Y. Shim, S.E. Lee, P. Sung, and G. Ira, "Cell cycle regulation of DNA double-strand break end resection by Cdk1-dependent Dna2 phosphorylation", Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, vol. 18, pp. 1015-1019, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nsmb.2105

- Y. Aylon, B. Liefshitz, and M. Kupiec, "The CDK regulates repair of double-strand breaks by homologous recombination during the cell cycle", The EMBO Journal, vol. 23, pp. 4868-4875, 2004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.emboj.7600469

- G. Ira, A. Pellicioli, A. Balijja, X. Wang, S. Fiorani, W. Carotenuto, G. Liberi, D. Bressan, L. Wan, N.M. Hollingsworth, J.E. Haber, and M. Foiani, "DNA end resection, homologous recombination and DNA damage checkpoint activation require CDK1", Nature, vol. 431, pp. 1011-1017, 2004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature02964

- M. Clerici, D. Mantiero, I. Guerini, G. Lucchini, and M.P. Longhese, "The Yku70–Yku80 complex contributes to regulate double‐strand break processing and checkpoint activation during the cell cycle", EMBO reports, vol. 9, pp. 810-818, 2008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/embor.2008.121

- V. Garcia, S.E.L. Phelps, S. Gray, and M.J. Neale, "Bidirectional resection of DNA double-strand breaks by Mre11 and Exo1", Nature, vol. 479, pp. 241-244, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature10515

- H. Lempiäinen, and T.D. Halazonetis, "Emerging common themes in regulation of PIKKs and PI3Ks", The EMBO Journal, vol. 28, pp. 3067-3073, 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/emboj.2009.281

- R. Bosotti, A. Isacchi, and E.L. Sonnhammer, "FAT: a novel domain in PIK-related kinases.", Trends in biochemical sciences, 2000. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10782091

- Y. Shiloh, and Y. Ziv, "The ATM protein kinase: regulating the cellular response to genotoxic stress, and more", Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, vol. 14, pp. 197-210, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrm3546

- T.T. Paull, "Mechanisms of ATM Activation", Annual Review of Biochemistry, vol. 84, pp. 711-738, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-biochem-060614-034335

- J.M. Brown, "M. Stephen Meyn, ataxia telangiectasia and cellular responses to DNA damage. Cancer Res., 55:5991-6001, 1995.", Cancer research, 1997. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9187137

- M.F. Lavin, and Y. Shiloh, "THE GENETIC DEFECT IN ATAXIA-TELANGIECTASIA", Annual Review of Immunology, vol. 15, pp. 177-202, 1997. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.177

- P.J. McKinnon, "ATM and ataxia telangiectasia", EMBO reports, vol. 5, pp. 772-776, 2004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.embor.7400210

- G.S. Stewart, R.S. Maser, T. Stankovic, D.A. Bressan, M.I. Kaplan, N.G. Jaspers, A. Raams, P.J. Byrd, J.H. Petrini, and A.R. Taylor, "The DNA Double-Strand Break Repair Gene hMRE11 Is Mutated in Individuals with an Ataxia-Telangiectasia-like Disorder", Cell, vol. 99, pp. 577-587, 1999. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81547-0

- A. Taylor, A. Groom, and P. Byrd, "Ataxia-telangiectasia-like disorder (ATLD)—its clinical presentation and molecular basis", DNA Repair, vol. 3, pp. 1219-1225, 2004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.04.009

- T. Uziel, "Requirement of the MRN complex for ATM activation by DNA damage", The EMBO Journal, vol. 22, pp. 5612-5621, 2003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/emboj/cdg541

- J. Falck, J. Coates, and S.P. Jackson, "Conserved modes of recruitment of ATM, ATR and DNA-PKcs to sites of DNA damage", Nature, vol. 434, pp. 605-611, 2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature03442

- Z. You, C. Chahwan, J. Bailis, T. Hunter, and P. Russell, "ATM Activation and Its Recruitment to Damaged DNA Require Binding to the C Terminus of Nbs1", Molecular and Cellular Biology, vol. 25, pp. 5363-5379, 2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.25.13.5363-5379.2005

- K. Fukunaga, Y. Kwon, P. Sung, and K. Sugimoto, "Activation of Protein Kinase Tel1 through Recognition of Protein-Bound DNA Ends", Molecular and Cellular Biology, vol. 31, pp. 1959-1971, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.05157-11

- J. Lee, and T.T. Paull, "Direct Activation of the ATM Protein Kinase by the Mre11/Rad50/Nbs1 Complex", Science, vol. 304, pp. 93-96, 2004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1091496

- J. Lee, and T.T. Paull, "ATM Activation by DNA Double-Strand Breaks Through the Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1 Complex", Science, vol. 308, pp. 551-554, 2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1108297

- A. Dupré, L. Boyer-Chatenet, and J. Gautier, "Two-step activation of ATM by DNA and the Mre11–Rad50–Nbs1 complex", Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, vol. 13, pp. 451-457, 2006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nsmb1090

- A.J. Lustig, and T.D. Petes, "Identification of yeast mutants with altered telomere structure.", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 83, pp. 1398-1402, 1986. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.83.5.1398

- P.W. Greenwell, S.L. Kronmal, S.E. Porter, J. Gassenhuber, B. Obermaier, and T.D. Petes, "TEL1, a gene involved in controlling telomere length in S. cerevisiae, is homologous to the human ataxia telangiectasia gene", Cell, vol. 82, pp. 823-829, 1995. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0092-8674(95)90479-4

- D.M. Morrow, D.A. Tagle, Y. Shiloh, F.S. Collins, and P. Hieter, "TEL1, an S. cerevisiae homolog of the human gene mutated in ataxia telangiectasia, is functionally related to the yeast checkpoint gene MEC1", Cell, vol. 82, pp. 831-840, 1995. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0092-8674(95)90480-8

- R.J. Wellinger, and V.A. Zakian, "Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About Saccharomyces cerevisiae Telomeres: Beginning to End", Genetics, vol. 191, pp. 1073-1105, 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1534/genetics.111.137851

- K.B. Ritchie, and T.D. Petes, "The Mre11p/Rad50p/Xrs2p complex and the Tel1p function in a single pathway for telomere maintenance in yeast.", Genetics, 2000. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10790418

- R.E. Hector, R.L. Shtofman, A. Ray, B. Chen, T. Nyun, K.L. Berkner, and K.W. Runge, "Tel1p preferentially associates with short telomeres to stimulate their elongation.", Molecular cell, 2007. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17803948

- M. Sabourin, C.T. Tuzon, and V.A. Zakian, "Telomerase and Tel1p Preferentially Associate with Short Telomeres in S. cerevisiae", Molecular Cell, vol. 27, pp. 550-561, 2007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2007.07.016

- D. Mantiero, M. Clerici, G. Lucchini, and M.P. Longhese, "Dual role for Saccharomyces cerevisiae Tel1 in the checkpoint response to double‐strand breaks", EMBO reports, vol. 8, pp. 380-387, 2007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.embor.7400911

- B. Shiotani, and L. Zou, "Single-Stranded DNA Orchestrates an ATM-to-ATR Switch at DNA Breaks", Molecular Cell, vol. 33, pp. 547-558, 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.024

- T. Usui, H. Ogawa, and J.H. Petrini, "A DNA Damage Response Pathway Controlled by Tel1 and the Mre11 Complex", Molecular Cell, vol. 7, pp. 1255-1266, 2001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00270-2

- A. Duursma, R. Driscoll, J. Elias, and K. Cimprich, "A Role for the MRN Complex in ATR Activation via TOPBP1 Recruitment", Molecular Cell, vol. 50, pp. 116-122, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2013.03.006

- T. Beyer, and T. Weinert, "Mec1 and Tel1: an arresting dance of resection", The EMBO Journal, pp. n/a-n/a, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/embj.201387440

- V. Paciotti, M. Clerici, G. Lucchini, and M.P. Longhese, "The checkpoint protein Ddc2, functionally related to S. pombe Rad26, interacts with Mec1 and is regulated by Mec1-dependent phosphorylation in budding yeast.", Genes & development, 2000. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10950868

- J. Rouse, and S.P. Jackson, "Lcd1p Recruits Mec1p to DNA Lesions In Vitro and In Vivo", Molecular Cell, vol. 9, pp. 857-869, 2002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00507-5

- L. Zou, and S.J. Elledge, "Sensing DNA Damage Through ATRIP Recognition of RPA-ssDNA Complexes", Science, vol. 300, pp. 1542-1548, 2003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1083430

- D. Nakada, Y. Hirano, Y. Tanaka, and K. Sugimoto, "Role of the C Terminus of Mec1 Checkpoint Kinase in Its Localization to Sites of DNA Damage", Molecular Biology of the Cell, vol. 16, pp. 5227-5235, 2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1091/mbc.E05-05-0405

- M. Hohl, T. Kochańczyk, C. Tous, A. Aguilera, A. Krężel, and J. Petrini, "Interdependence of the Rad50 Hook and Globular Domain Functions", Molecular Cell, vol. 57, pp. 479-491, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2014.12.018

- N. Nassif, J. Penney, S. Pal, W.R. Engels, and G.B. Gloor, "Efficient copying of nonhomologous sequences from ectopic sites via P-element-induced gap repair.", Molecular and Cellular Biology, vol. 14, pp. 1613-1625, 1994. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.14.3.1613

- D.O. Ferguson, and W.K. Holloman, "Recombinational repair of gaps in DNA is asymmetric in Ustilago maydis and can be explained by a migrating D-loop model.", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 93, pp. 5419-5424, 1996. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.93.11.5419

- F. Pâques, W. Leung, and J.E. Haber, "Expansions and Contractions in a Tandem Repeat Induced by Double-Strand Break Repair", Molecular and Cellular Biology, vol. 18, pp. 2045-2054, 1998. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.18.4.2045

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Giovanna Lucchini and Michela Clerici for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC) (grant IG15210) to MPL. CC was supported by a fellowship from Fondazione Italiana Ricerca sul Cancro (FIRC).

COPYRIGHT

© 2016

Functions and regulation of the MRX complex at DNA double-strand breaks by Gobbini et al. is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.