Research Articles:

Microbial Cell, Vol. 5, No. 5, pp. 233 - 248; doi: 10.15698/mic2018.05.630

Spontaneous mutations in CYC8 and MIG1 suppress the short chronological lifespan of budding yeast lacking SNF1/AMPK

1 Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Genetics, University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville, VA 22908.

2 Department of Laboratory Medicine, Jilin Medical University, Jilin, 132013, China.

# Equally contributed to the work.

Keywords: Snf1, AMPK, Cyc8, Cat8, aging, yeast, chronological lifespan, TPR.

Received originally: 03/09/2017 Received in revised form: 10/02/2018

Accepted: 12/02/2018

Published: 19/02/2018

Correspondence:

Jeffrey S. Smith, Phone: 434-243-5864; jss5y@virginia.edu

Conflict of interest statement: The authors have no conflicts of interests.

Please cite this article as: Nazif Maqani, Ryan D. Fine, Mehreen Shahid, Mingguang Li, Elisa Enriquez-Hesles and Jeffrey S. Smith (2018). Spontaneous mutations in CYC8 and MIG1 suppress the short chronological lifespan of budding yeast lacking SNF1/AMPK. Microbial Cell 5(5): 233-248. doi: 10.15698/mic2018.05.630

Abstract

Chronologically aging yeast cells are prone to adaptive regrowth, whereby mutants with a survival advantage spontaneously appear and re-enter the cell cycle in stationary phase cultures. Adaptive regrowth is especially noticeable with short-lived strains, including those defective for SNF1, the homolog of mammalian AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK). SNF1 becomes active in response to multiple environmental stresses that occur in chronologically aging cells, including glucose depletion and oxidative stress. SNF1 is also required for the extension of chronological lifespan (CLS) by caloric restriction (CR) as defined as limiting glucose at the time of culture inoculation. To identify specific downstream SNF1 targets responsible for CLS extension during CR, we screened for adaptive regrowth mutants that restore chronological longevity to a short-lived snf1∆ parental strain. Whole genome sequencing of the adapted mutants revealed missense mutations in TPR motifs 9 and 10 of the transcriptional co-repressor Cyc8 that specifically mediate repression through the transcriptional repressor Mig1. Another mutation occurred in MIG1 itself, thus implicating the activation of Mig1-repressed genes as a key function of SNF1 in maintaining CLS. Consistent with this conclusion, the cyc8 TPR mutations partially restored growth on alternative carbon sources and significantly extended CLS compared to the snf1∆ parent. Furthermore, cyc8 TPR mutations reactivated multiple Mig1-repressed genes, including the transcription factor gene CAT8, which is responsible for activating genes of the glyoxylate and gluconeogenesis pathways. Deleting CAT8 completely blocked CLS extension by the cyc8 TPR mutations on CLS, identifying these pathways as key Snf1-regulated CLS determinants.

INTRODUCTION

The budding yeast SNF1 complex is homologous to metazoan AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), and acts as a sensor of cellular energy status that adjusts metabolism in response to environmental nutrient conditions and stress [1][2][3]. Like AMPK, SNF1 is a heterotrimer consisting of a catalytic α-subunit (Snf1), an activating γ-subunit (Snf4), and one of three possible β-subunits (Gal83, Sip1, Sip2) that tether Snf1 and Snf4 together and contribute to cellular localization and substrate specificity for the kinase activity [3][4]. Snf1 is activated by low glucose concentrations through phosphorylation of its activation loop at threonine 210 by one of three upstream kinases (Sak1, Tos3, Elm1) [5]. Snf4 regulates accessibility of phosphorylated T210 to the phosphatase Glc7, such that under low glucose conditions, ADP association with the Snf4 γ-subunit protects Snf1 T210 from dephosphorylation [6][7].

–

Saccharomyces cerevisiae is a facultative anaerobe that prefers to utilize glycolysis and fermentation for producing ATP and carbon skeletons, rather than the mitochondrial TCA cycle and oxidative phosphorylation, to support rapid cell proliferation under aerobic conditions. SNF1 alters metabolism in response to low environmental glucose in part by phosphorylating metabolic enzymes such as acetyl CoA carboxylase (ACC). ACC converts acetyl CoA into malonyl CoA, which is the rate-limiting step of de novo fatty acid biosynthesis [8]. Snf1 phosphorylation of Acc1 inactivates the enzyme, thus promoting fatty acid catabolism and accumulation of acetyl CoA, which then contributes to histone acetylation and transcriptional activity stimulated by low glucose [9]. Snf1 also functions more directly in transcriptional activation by phosphorylating several transcription factors (Mig1, Cat8 and others) that are responsible for diminishing glycolysis/fermentation pathways and promoting the utilization of alternative carbon sources such as ethanol and acetate [2]. This transition in transcription and metabolism is known as the diauxic shift, and is important for long-term cell survival in stationary phase cultures [10].

–

The period of yeast cell survival during stationary phase is also known as chronological lifespan (CLS), which is commonly used as a simple model for aging of non-mitotic cells [11]. CLS is typically measured by assaying cell viability in liquid cultures either by the ability to form colonies on fresh media or using viability dyes such as FUN-1 and propidium iodide [12]. Numerous genetic modifications and environmental conditions impact CLS. For example, CLS is extended by inhibiting the TOR signaling pathway [13], which is also observed for metazoan models of aging ranging from C. elegans to mice [14]. CLS is also significantly extended by reducing glucose concentration at the time of culture inoculation from 2% (non-restricted/NR) to 0.5% (calorie restricted/CR) [15]. CR in this context has a significant impact on gene expression and cellular physiology during the diauxic shift and into stationary phase [16]. CR also prevents the accumulation of organic acids like acetic acid in the growth medium [17][18], which can have detrimental effects on cell viability during chronological aging [17].

–

One of the mechanisms by which CR prevents acetic acid accumulation is by promoting acetate consumption, as evidenced by genes involved in alternative carbon source utilization being among the most abundant gene class upregulated by CR in aging cells [16]. Consistent with ethanol and acetate consumption, CR prevents acetyl CoA depletion of cells in stationary phase cultures, most likely due to the combined action of Snf1 in phosphorylating ACC and in preventing inactivation of acetyl CoA synthetase genes ACS1 and ACS2 during the diauxic shift and into stationary phase [19]. While SNF1 is best known for its role in derepressing genes in the absence of glucose, including genes involved in fatty acid oxidation and utilization of non-fermentable carbon sources [20], it also regulates the cellular responses to oxidative stress [21] and DNA damage [22][23], all of which can impact yeast chronological lifespan [24]. SNF1 is critical for maintaining CLS and is required for the extension of CLS induced by CR growth conditions [18][19][25], raising the question of which downstream SNF1 targets or cellular processes are most critical for cell survival, and which could also have important implications for cell survival mechanisms regulated by AMPK. To identify critical aging-relevant downstream targets of Snf1, we screened for adaptive regrowth from chronologically aging cultures of snf1∆ cells and utilized whole genome DNA sequencing of the adapted isolates to identify any mutated genes. Remarkably, almost every isolate had a mutation in specific TPR (tetratricopeptide repeat) motifs of the transcriptional co-repressor CYC8 that mediate Mig1-dependent repression of genes normally activated by SNF1 during the diauxic shift. RNA-seq and qRT-PCR revealed at least partial transcriptional restoration to a subset of such genes with Mig1 binding sites, including CAT8, a transcriptional activator of glyoxylate and gluconeogenesis pathway genes. CAT8 was also required for the restoration of longevity in adapted isolates, thus implicating transcriptional derepression of CAT8 as a key SNF1 function in maintaining CLS.

RESULTS

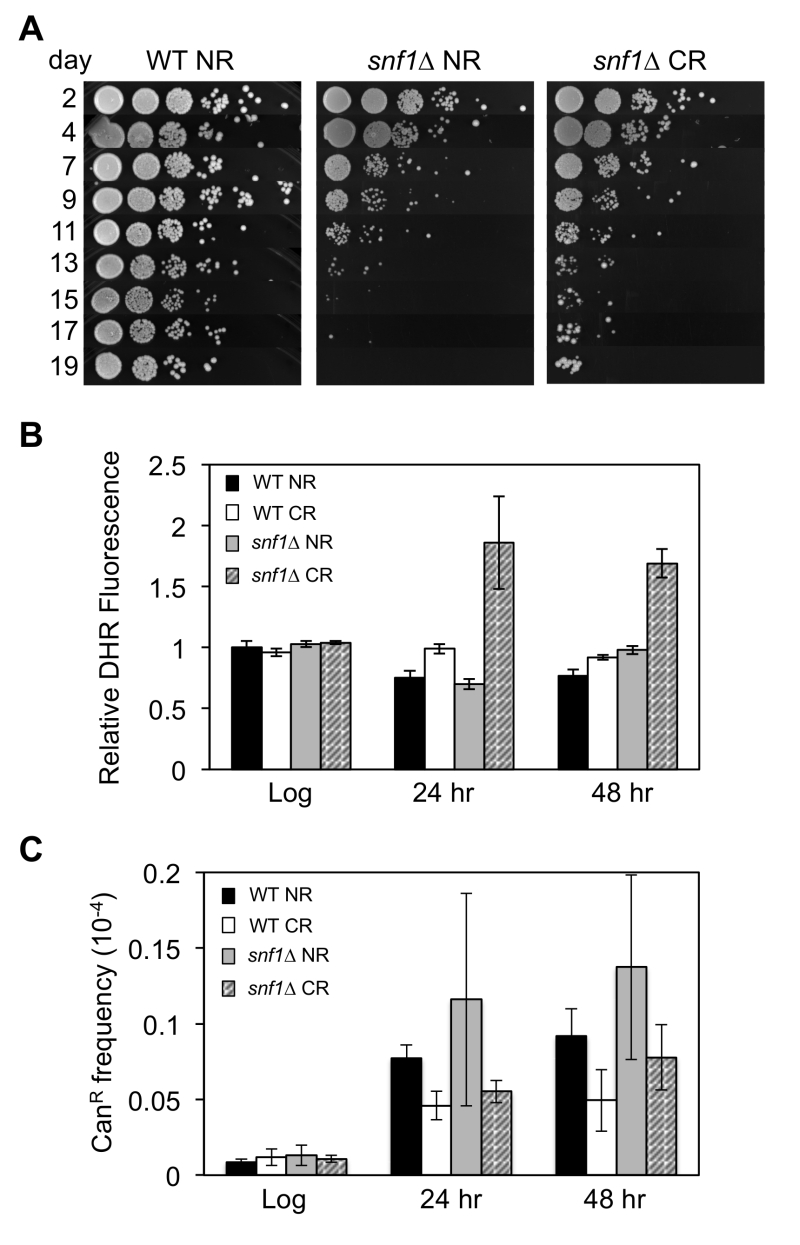

Cells deleted for the SNF1 gene have a very short CLS under both NR and CR growth conditions [19]. However, we often observe a phenomenon known as adaptive regrowth or “gasping” in snf1∆ cultures, especially under CR. When this happens, cell viability drops rapidly during the first 11 days for the snf1∆ mutant, but then eventually stabilizes or even recovers thereafter (Fig. 1A), as cells within the population are able to re-enter the cell cycle and slowly proliferate. Adaptive regrowth was previously shown to occur through uncharacterized genetic mutations that presumably allow utilization of nutrients released into the medium by dying cells [26]. Since SNF1 targets multiple transcription factors, metabolic enzymes, and even histone H3 [27], we hypothesized that mutations in genes allowing snf1∆ cells to survive in stationary phase during chronological aging would reveal critical targets or cellular processes that Snf1 regulates to promote CLS.

–

Yeast cultures under CR conditions (0.5% glucose) tend to accumulate reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the form of H2O2 during chronological aging [28]. This results in a hormetic response, which activates superoxide dismutases that contribute to enhanced cell viability. One possible reason for the frequent adaptive regrowth of snf1∆ strains could therefore be elevated ROS levels that drive mutagenesis. Indeed, cellular staining with dihydrorhodamine (DHR) detected significantly elevated ROS levels in the calorie restricted snf1∆ mutant post-log phase after 24 or 48 hr of growth (Fig. 1B). However, mutation frequency at the CAN1 gene was not significantly higher in the snf1∆ mutant compared to WT (Fig. 1C). It is therefore possible that high ROS levels in the snf1∆ mutant contribute to DNA damage that is effectively repaired, but the CR condition provides a strong selective pressure or ideal growth condition for specific classes of mutants to adapt.

–

A genetic screen for snf1∆ CLS bypass suppressor mutations

To identify snf1∆ bypass suppressors, we took advantage of the frequent adaptive regrowth observed for the snf1∆ strain as observed in Fig. 1A. Single colonies of the snf1∆ strain JS1394 were purified and independently inoculated into 10 different SC (0.5% glucose) cultures (A1-A10), which were then chronologically aged. 10-fold serial dilutions were spotted onto rich YPD agar plates every 2 or 3 days to monitor for adaptive regrowth, which was easily noticeable as sustained and enlarged colony growth after approximately 11 days (Fig. 1A, CR culture). Putative adapted mutants were chosen from the YPD plates as they appeared starting at day 11, with three candidates picked and single colony purified from culture A1. Over subsequent days, 2 candidate mutants were picked from most of the other cultures (up to day 17) for a total of 20 candidates (Table 1). Only 1 candidate was isolated from culture A7.

–

Cells lacking SNF1 are unable to grow on alternative carbon sources such as glycerol, ethanol, or acetate [29]. To test if the CLS-adapted snf1∆ mutants restored this abil-ity, 10-fold serial dilutions of each strain were spotted onto rich yeast extract/peptone (YEP) plates containing glucose, ethanol/glycerol, or acetate. As shown in Fig. 2A, the snf1∆ parental strain (JS1394) grew poorly on ethanol/glycerol and acetate plates, as expected. Each adapted mutant showed improved growth on both types of plates, suggesting they gained one or more secondary mutations that partially restored alternative carbon source utilization. We next used these growth phenotypes to test if the putative mutations were recessive or dominant by crossing each adapted strain to a snf1∆ mutant of the opposite (MATα) mating type, thus generating homozygous snf1∆/snf1∆ diploids that were heterozygous for any other mutated loci. The restoration of growth on ethanol/glycerol and acetate plates observed with haploids was lost from most of the diploids, indicative of recessive alleles (Fig. 2A and Table 1). However, several diploids such as E4 did grow modestly better than the snf1∆/snf1∆ control diploid (C3), so they were considered semi-dominant. Next, several candidates from the screen were quantitatively retested for CLS under NR and CR conditions (Fig. 2B). The CLS of each candidate was longer than the snf1∆ parent (JS1394), but not as long as WT (JS1256). This partial recovery of CLS was similar to the partial growth phenotype observed on alternative carbon sources (Fig. 2A). CR slightly increased CLS of the snf1∆ parent, as previously described [19], but shortened CLS of two adapted mutants (JS1413, JS1418), as compared to NR (Fig. 2B). CLS of the semi-dominant A2-1 (JS1416) mutant was unaffected by CR. Importantly, CR did not extend CLS for any of the adapted mutants tested, suggesting that CR partially works through whichever functional gene(s) were mutated.

–

Next, genomic DNA was prepared from each adapted mutant, as well as the snf1∆ parent (JS1394), and Illumina DNA sequencing libraries were constructed using an NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Prep Kit (New England Biolabs). Libraries were multiplexed and sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq apparatus, then aligned to the S. cerevisiae genome. SNPs specific to the adapted mutants with maximum quality scores and within open reading frames or promoters were identified and listed in Table 1. Mutations found in more than one isolate from a particular culture (i.e. A1-1, A1-2, and A1-3) were considered to be derived from the same progenitor cell. Taking this into account, a total of 23 unique mutations were recovered from 19 sequenced candidates, with the majority (15) occurring at cytosines. Consistent with mutagenesis caused by high ROS levels, oxidation products of cytosine such as 5-hydroxycytosine and 5-hydroxyuracil commonly result in C to T transitions and C to G transversions [30], which were the two most abundant mutation classes from the screen.

–

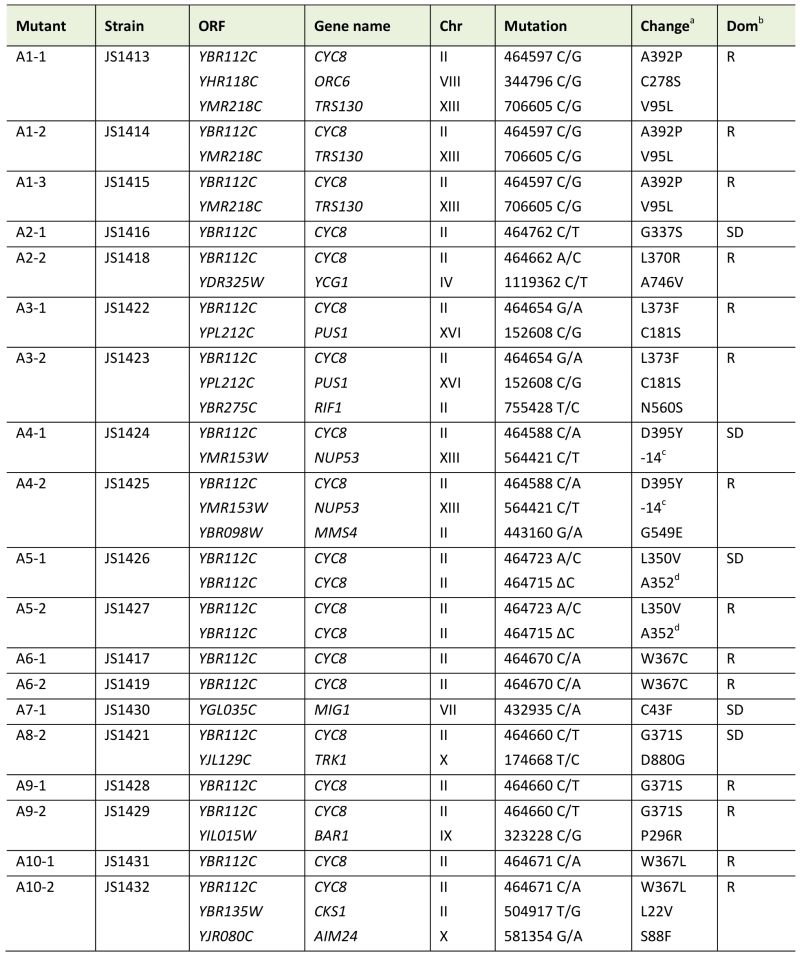

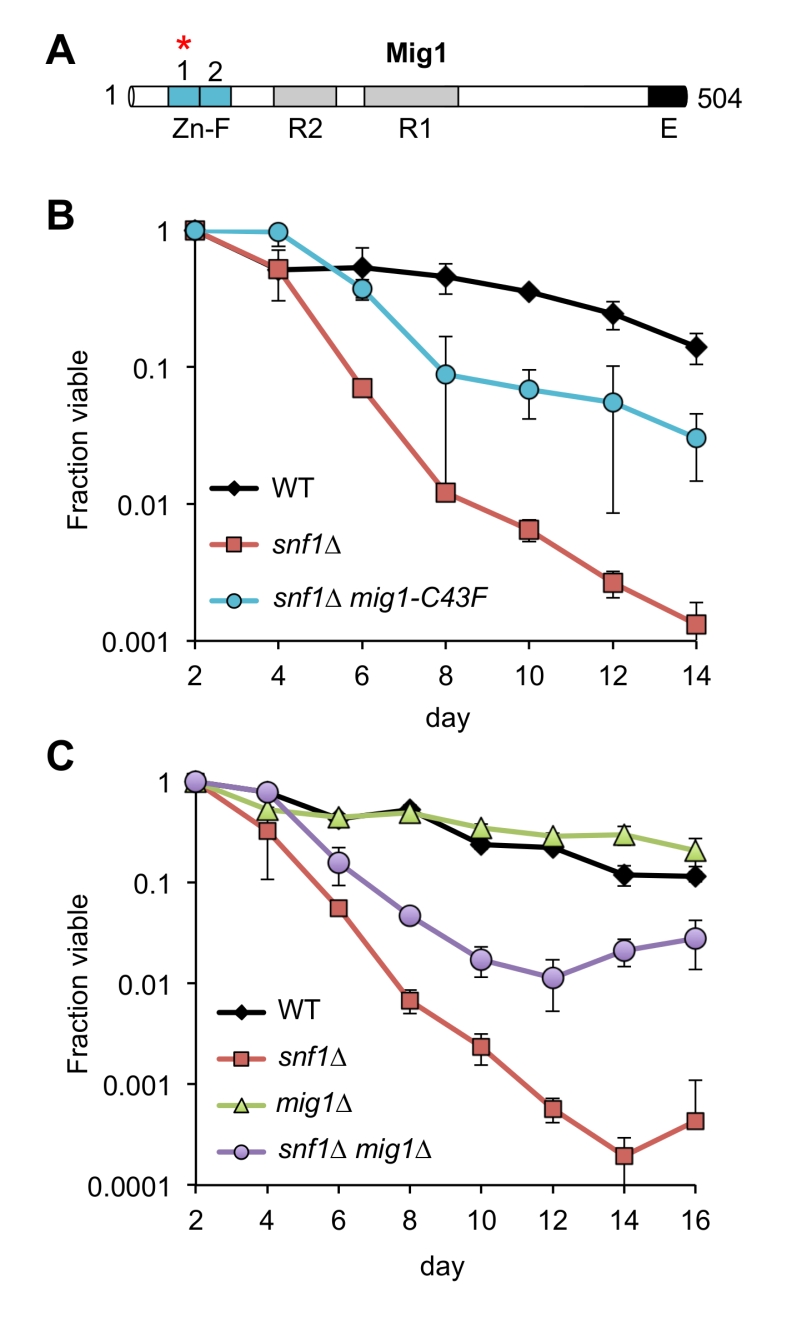

Remarkably, every adapted mutant other than A7-1 (JS1430) had a mutation in the CYC8 gene, which encodes a subunit of the Cyc8/Tup1 corepressor complex that transcriptionally represses a large number of genes controlling mating-type, cell cycle, glucose repression, and others [31]. CYC8 was also the only mutated gene in 5 of the adapted mutants, clearly implicating CYC8 as functionally relevant to the snf1∆ suppression phenotype. Furthermore, the only mutation in A7-1 caused a C43F amino acid substitution in Mig1, a transcriptional repressor that physically interacts with Cyc8/Tup1 at specific gene promoters under glucose repression and is a direct phosphorylation target of SNF1 [32]. Mig1 is a zinc finger protein that binds to 5’-MCCCCRS-3’ motifs of certain genes under glucose repression [33][34]. Cys43 is located in the first of two C2H2 zinc finger motifs that mediate DNA binding by Mig1 (Fig. 3A), so the C43F mutation in A7-1 (JS1430) is predicted to generally disrupt Mig1 function by preventing association with target gene promoters. If this were true, then simply deleting MIG1 should produce the same snf1∆ suppression CLS phenotype as C43F. As shown in Fig. 3B, the short CLS of a snf1∆ mutant was extended by mig1-C43F. Similarly, deleting MIG1 also partially suppressed the short snf1∆ CLS phenotype (Fig. 3C), thus implicating transcriptional release of Mig1 target gene repression as a critical Snf1 function for maintaining CLS. Since Snf1 phosphorylation of Mig1 normally activates Mig1-repressed genes under low glucose conditions such as the diauxic shift period [35], we hypothesized that impairing Mig1 and/or Cyc8 function was facilitating transcription of such genes in the absence of Snf1, thus bypassing the snf1∆ mutation.

–

| FIGURE 3: Mutations in MIG1 partially restore CLS to a snf1∆ strain. (A) Diagram of Mig1 protein domain organization showing the two zinc fingers (Zn-F), two regulatory domains (R1 and R2) and an effector domain (E) [36]. Red asterisk indicates the zinc finger mutated (C43F) in suppressor candidate JS1430. (B) Quantitative CLS assay showing short CLS of snf1∆ (JS1394) compared to WT (JS1256). The snf1∆ mig1-C43F mutant (JS1430) extends CLS compared to snf1∆. (C) Quantitative CLS assay showing similar partial CLS extension by deleting MIG1 in the snf1∆ background (JS1446). Deletion of MIG1 had little CLS effect on its own (JS1442). CLS assays were performed in SC 2% glucose conditions. Error bars indicate standard deviation. |

Mutations in specific TPR motifs of CYC8 restore CLS to cells lacking SNF1

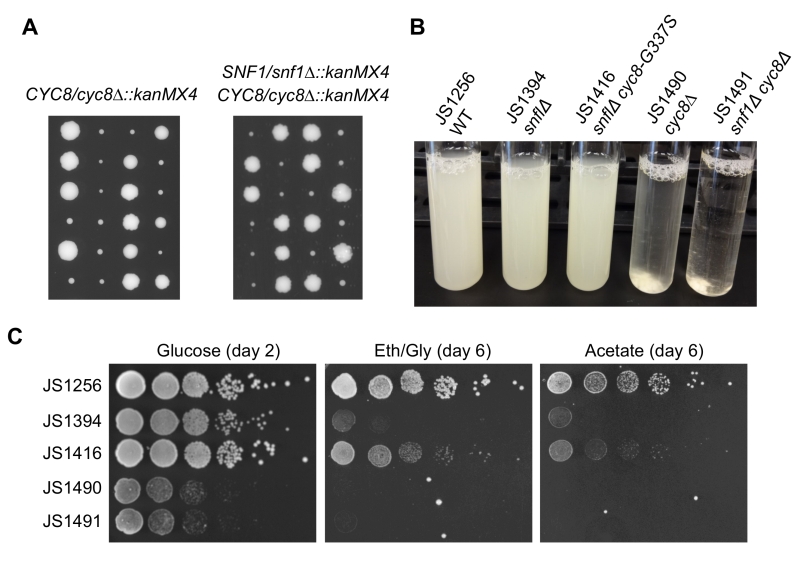

SNF1 (sucrose non-fermenting) was originally described as a mutation that prevents growth on sucrose due to an inability to express SUC2, a glucose-repressed gene encoding the sucrose hydrolyzing enzyme invertase [36]. Another name for CYC8 is SSN6, which stands for suppressor of snf1 [37]. Mutations in CYC8 were identified as cyc1-13 revertants that restore growth on lactate due to increased expression of cytochrome C [38], while mutations in SSN6 were identified as revertants that allow snf1 mutants to grow on sucrose [37]. The cyc8 and ssn6 mutations turned out to be allelic and were eventually shown to derepress transcription of glucose-repressed genes that require Snf1 for their activation under low glucose conditions. Several other “SSN” genes have been described, including several subunits of the Mediator complex [39], but only cyc8/ssn6 and mig1/ssn1 mutations were identified from our screen for CLS extension of a snf1∆ mutant. Additionally, all but one of the cyc8 mutations were missense amino acid substitutions, suggesting that complete elimination of Cyc8 protein could be detrimental. To determine if deleting CYC8 would have the same suppression effect as observed with the snf1∆ mig1∆ mutant (Fig. 3B), we generated cyc8∆::kanMX snf1∆::kanMX double mutants through genetic crossing and tetrad dissection. All resulting cyc8∆ spores grew poorly regardless of the accompanying SNF1 allele (Fig. 4A), and were highly flocculent (Fig. 4B), consistent with previously described Cyc8/Tup1-dependent repression of flocculence genes such as FLO1 [40]. In stark contrast, the adapted snf1∆ cyc8 mutants all grew robustly (Fig 2A and 4B), and were highly dispersed in liquid culture, similar to WT and snf1∆ strains (Fig. 4B, JS1416 shown as example). Furthermore, snf1∆ cyc8∆ strains did not grow at all with ethanol/glycerol or acetate provided as the carbon sources (Fig. 4C), implying that cyc8 mutations isolated in the CLS screen were highly specialized.

–

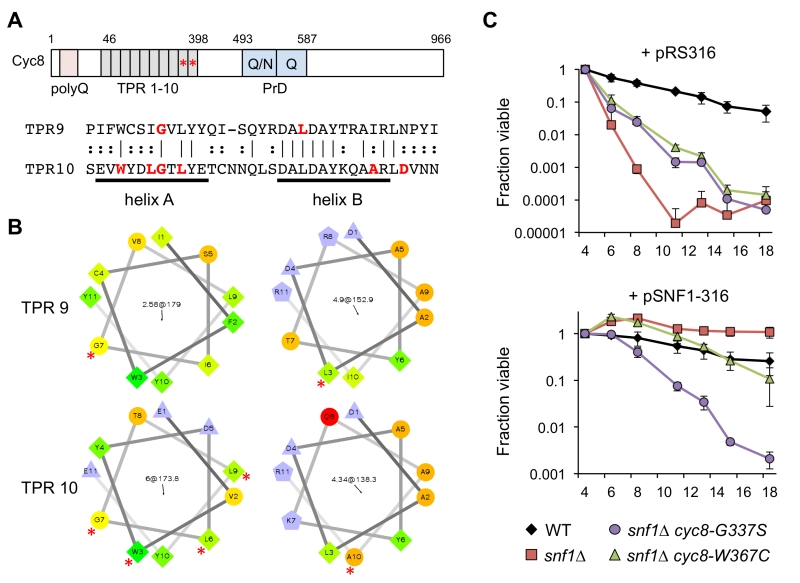

Closer inspection of the cyc8 mutations showed they all occurred in the 9th or 10th TPRs of an N-terminally located tandem array (Fig. 5A and Table 1). TPR motifs consist of two amphipathic α-helices (A and B) that mediate physical interactions with other proteins [41]. All but one of the amino acids altered by missense mutation was hydrophobic and located within the predicted A and B α-helices (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, each altered amino acid was predicted by helical wheel projections to be on the hydrophobic face of either helix A or B (Fig. 5B), suggesting the mutations altered specific hydrophobic protein-protein interactions between Cyc8 and an associated factor. The most likely associated factor is Mig1 because the TPR8-10 motifs of Cyc8 mediate transcriptional repression by Mig1 [42]. There were no mutations identified within TPR8 from our screen, suggesting that TPR9 and TPR10 provide most of the function relevant to CLS.

–

| FIGURE 5: Adaptive Cyc8 mutations are specific to the TPR9 and TPR10 mo-tifs. (A) Domain organization of the Cyc8 protein, indicating an N-terminal poly-glutamine (polyQ) tract, an array of 10 TPR motifs from amino acids 46 to 398, and the prion domain (PrD) consisting of polyQ/N and polyQ repeats. Asterisks indicate the location of mutations in the TPR9 and TPR10 motifs. An alignment of the TPR9 and TPR10 motifs is shown, indicating amino acids that were changed in the adapted strains. Note the mutations are distributed across the characteristic amphipathic α-helices. (B) Helical wheel representation of the A and B α-helices of TPR9 and TPR10 generated online (http://rzlab.ucr.edu/scripts/wheel/wheel.cgi). Mutated residues are indicated by an asterisk. (C) Quantitative CLS when SNF1 is restored to a cyc8 TPR9 mutant (JS1416, snf1∆ cyc8-G337S) or a cyc8 TPR10 mutant (JS1417, snf1∆ cyc8-W367C) by transformation with a CEN-ARS URA3 plasmid containing the SNF1 gene (pSNF1-316). The empty URA3 vector (pRS316) was also transformed as a control. Cells were maintained in SC-ura medium with 2% glucose throughout the experiment. Error bars indicate standard deviations. |

Under activating growth conditions, the bulk of Mig1 is exported from the nucleus [43]. However, significant levels of Mig1 and Cyc8/Tup1 remain associated with target gene promoters such as GAL1 and help recruit the SAGA co-activator complex [44], arguing that Cyc8/Tup1 is a transcriptional “co-regulator” rather than just a co-repressor. We therefore hypothesized that the TPR9 or TPR10 mutations in CYC8 could potentially impact CLS independent of the snf1∆ mutation. To test this idea, SNF1 was restored in a TPR9 mutant (JS1416) and TPR10 mutant (JS1417) by transformation with a CEN/ARS plasmid containing the SNF1 gene (pSNF1-316), or an empty control plasmid (pRS316). Transformants were then quantitatively assayed for CLS in non-restricted (2% glucose) SC medium lacking uracil to maintain the plasmid. As shown in Fig. 5C, both mutants showed the expected partial CLS extension compared to snf1∆ when transformed with pRS316, recapitulating CLS suppression results from Fig. 2B. However, the TPR9 mutant (snf1∆ cyc8-G337S) remained short lived when transformed with pSNF1-316, while CLS of the TPR10 mutant (snf1∆ cyc8-W367C) was restored to normal (Fig. 5C). The cyc8-G337S mutation therefore impaired CLS in-dependently of SNF1, perhaps due to altered interactions with other transcription factors that associate with the TPR9 motif rather than TPR10. Such a model is also supported by the semi-dominant growth phenotype of this mutant on ethanol/glycerol or acetate media (Fig. 2A).

–

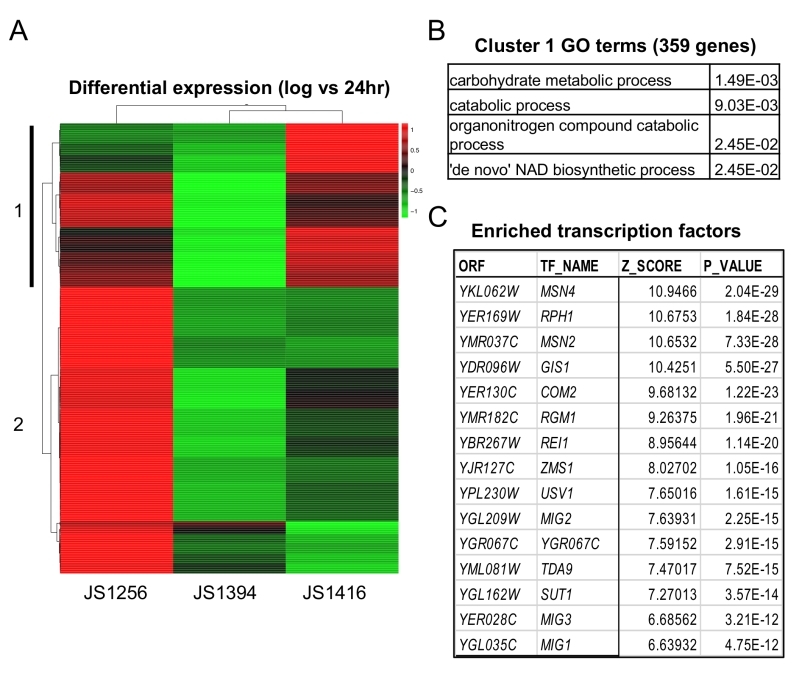

Next, RNA-seq analysis was performed on WT (JS1256), snf1∆ (JS1394) and the cyc8-G337S mutant (JS1416) that were grown for 6 (log), 24, or 48 hrs. Analysis focused on 986 genes that were upregulated at 24hr compared to log in the WT strain, but not in snf1∆. Unsupervised cluster analysis revealed a subset of 359 genes whose expression was at least partially restored in the suppressor strain (Fig. 6A). These genes were significantly enriched for catabolic processes and surprisingly, de novo NAD+ biosynthesis (Fig. 6B). As predicted, Mig1 binding sites were significantly enriched on the promoters of these genes, as were its related factors Mig2 and Mig3 (Fig. 6C), which appear to fine-tune glucose repression [45]. However, among the top hits in P-value were four other transcription factors (Msn2/Msn4, Gis1 and Rph1) that are known multi-copy suppressors of snf1-defective phenotypes [46][47]. Msn2/4 are major transcriptional activators for the general stress response [48], and Gis1/Rph1 are paralogous histone H3-K36 demethylases that can act as repressors or activators depending on the gene and the growth condition, including glycerol and acetate metabolism [2]. Perhaps the cyc8-G337S mutation disrupts proper transcriptional regulation mediated by one or more of these, or other highly enriched factors listed in Fig. 6C and supplementary Table S3.

–

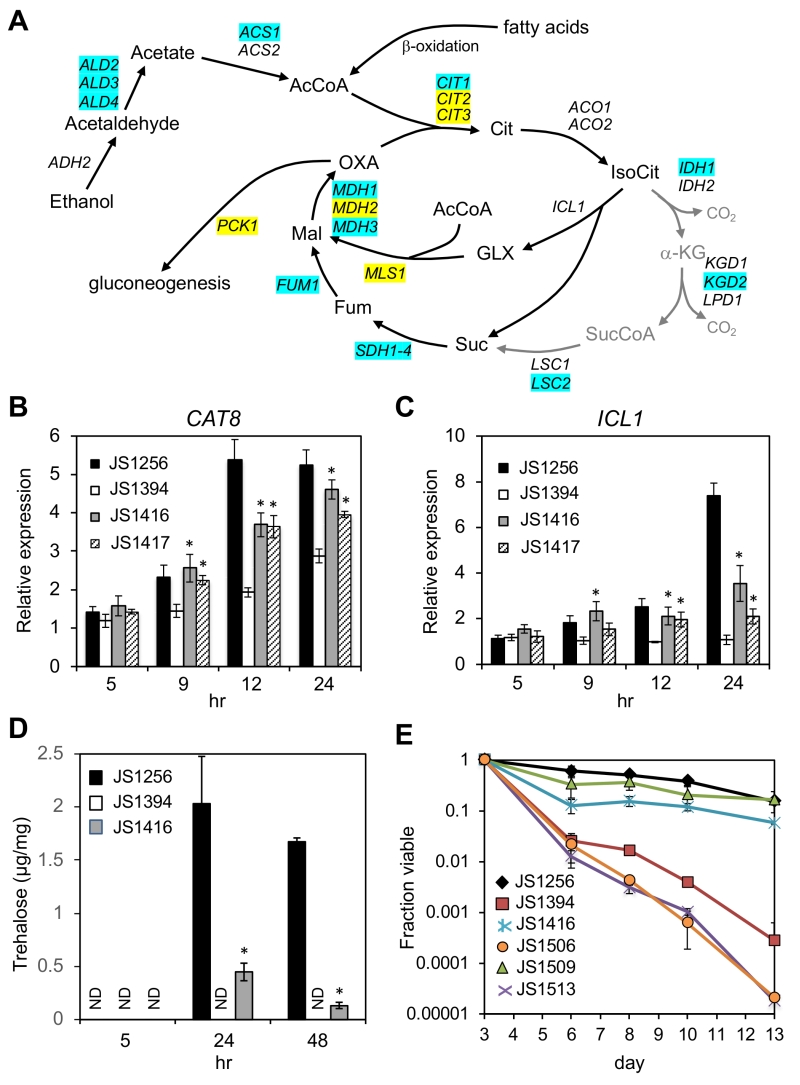

Bypass suppression of snf1∆ by cyc8-G337S is CAT8-dependent

Snf1 phosphorylates Mig1 under low glucose conditions to activate genes for alternative carbon source utilization [32]. Among these targets is CAT8, which encodes a zinc cluster transcriptional activator of glyoxylate and gluconeogenesis pathway genes such as ICL1, MLS1, and PCK1 (Fig. 6A) [49][50]. The Cat8 protein is also directly activated by Snf1-dependent phosphorylation [51][52], and further transactivates its own gene as a positive feedback [53]. CAT8 is required for CR-mediated extension of CLS and for CR-amplified expression of select target genes during the diauxic shift, including the acetyl CoA synthetase gene ACS1 [19]. Accordingly, ACS1 transcription was partially restored in the snf1∆ cyc8-G337S suppressor mutant (JS1416) compared to the snf1∆ mutant (JS1394) as measured through RNA-seq, as were numerous other genes that function in ethanol and acetate catabolism (Fig. 7A; Supplemental Tables S1 and S2). CAT8 was among the significantly enriched transcription factors on the promoters of such genes (Supplemental Table S3; p = 1.58E-06), and qRT-PCR analysis confirmed its transcription was partially restored in JS1416 compared to JS1394 (Fig. 7B). Surprisingly, CAT8 transcription levels modestly increased over time in the snf1∆ mutant, suggesting that additional Snf1-independent factors contribute to its activation. The key glyoxylate cycle gene ICL1 (isocitrate lyase) was absent from the lists of genes with improved expression after 24 hr and 48 hr (Fig. 7A; Supplemental Tables S1 and S2), but we confirmed its expression was elevated using qRT-PCR (Fig. 7C). Unlike the CAT8 gene, ICL1 expression did not increase over time in the snf1∆ mutant (Fig. 7C), indicating it is normally more dependent on Snf1 for activation. Consistent with a partial restoration of glyoxylate cycle gene expression, trehalose accumulation driven by gluconeogenesis was absent from the snf1∆ mutant at 24 and 48 hr, but noticeably recovered in the cyc8-G337S suppressor (Fig. 7D). This is significant because trehalose accumulation during the post-diauxic shift period (~24 hr in our system) was previously linked with CLS extension by CR [54], and glyoxylate/gluconeogenesis flux to trehalose appears to favor quiescence more so than mitochondrial respiration [55][56].

–

Since CAT8 expression was restored in the adapted mutants and CAT8 was required for CLS extension by CR [19], we hypothesized that longevity in the adapted snf1∆ mutants was also mediated by CAT8. Importantly, deleting CAT8 by itself has little effect on CLS in non-restricted SC medium ([19] and Fig. 7E, JS1509), perhaps due to redundancy with other factors such as Adr1 and Sip4. However, deleting CAT8 from the JS1416 (snf1∆ cyc8-G337S) isolate completely blocked longevity of the resulting snf1∆ cyc8-G337S cat8∆ triple mutant (JS1506) when grown in non-restricted SC media (Fig. 7E). We therefore conclude that the cyc8-G337S mutation isolated under CR growth conditions is compensating for a critical long-term survival function normally carried out by Snf1 during CR, namely the relief of transcriptional glucose repression. Limited CLS recovery and partially restored expression of numerous non-Mig1 target genes in the suppressors also indicate that additional Snf1-driven processes significantly contribute to achieving maximal CLS in normal cells under non-restricted conditions.

DISCUSSION

SNF1 clearly supports cell survival when culture medium is depleted for glucose, the highly preferred carbon source of budding yeast. Cells lacking the Snf1 α-subunit or Snf4 γ-subunit fail to even grow when solely provided with less favorable carbon sources such as ethanol, acetate, glycerol, or sucrose [2]. The SNF gene name derives from Sucrose Non-Fermenting because such genes are required for expression of SUC2, which encodes the sucrose hydrolyzing enzyme invertase [36][57]. Suppressor mutations were originally identified in snf1 mutant strains by isolating re-vertant colonies that grew on sucrose-containing or othertypes of alternative carbon sources [37][38]. This is how the SSN genes were identified, including CYC8/SSN6. In the current study we identified adaptations that extended CLS of a snf1∆ parental strain, rather than restoring exponential growth on an alternative carbon source. In addition to relaxing glucose repression of gene expression, SNF1 also directly or indirectly regulates other transcription factors, kinases, and metabolic enzymes [58]. Given such diversity in SNF1 targets, we anticipated that multiple cellular processes would be identified from the screen, including stress resistance pathways, metabolism, and transcription. The idea was to find the key processes that drive Snf1-dependent longevity. It was therefore quite remarkable and telling that the adaptive mutations were so specific to CYC8 and MIG1. This clearly implicated the Mig1-mediated glucose repression system in CLS and CR, but did not rule out contributions from other downstream Snf1 targets (direct or indirect), especially since the suppressive effect of cyc8 and mig1 mutations was partial. Indeed, RNA-seq analysis for one of the adapted mutants (JS1416) indicated numerous Snf1-dependent genes whose transcription was at least partially restored by the cyc8 G337S mutation. Many of these genes harbored Msn2/4, Gis1, or Rph1 bind-ing sites in their promoters, which is significant because overexpression of these transcription factors suppresses phenotypic defects of snf1 mutants [46][47]. We therefore hypothesize that a combination of Snf1-driven processes are required for maximal CLS, not just relief of glucose repression. It is possible that other types of suppressor mutations would be identified with additional screening for adaptive mutants, or transcriptional relief of glucose repression is the only suppressible Snf1-dependent process that supports entry into quiescence, a property important for stationary phase survival.

–

Cyc8/Tup1 is a general transcriptional co-repressor complex that interacts with several different repressors of various cellular processes, including Mig1 (glucose repression), MATα2 (mating type gene regulation), Rfx1 (DNA damage regulated genes), and Sko1 (osmotic and oxidative stress response) [31]. Interestingly, a common theme for some of these factors is that they not only function as transcriptional repressors, but also contribute to activation under specific conditions [35][59][60]. For example, under activating conditions like growth on galactose or ethanol, Cyc8/Tup1 forms a complex with Cti6 and phosphoinositol (3,5) bisphosphate to function as a co-activator with Mig1, aiding in recruitment of the SAGA histone acetyltransferase complex to affected genes [44][61][62]. Cyc8/Tup1 is thought to mask the activation domain of Mig1 through physical interaction [63]. Phosphorylation of Mig1 by SNF1 in response to low glucose then alters the interaction such that its activation domain is unmasked [35][63]. With Mig1 and Cyc8/Tup1 being important for the Snf1-mediated transition from glycolysis/fermentation to respiration and gluconeogenesis, it is likely the adaptive Cyc8 mutations identified as CLS bypass suppressors disrupt masking by Cyc8/Tup1 while still allowing for transcriptional activation. This is consistent with the large number of genes in the JS1416 suppressor strain that are super-activated compared to snf1∆ or even the WT strain (Supplemental Tables S1 and S3). It is not clear whether specific TPR motifs or other domains of Cyc8 are required for interaction with the SAGA complex, though phosphoinositol (3,5) bisphosphate and Cti6 direct the transition from co-repressor to co-activator [44][62].

–

Some of the adapted snf1∆ mutants have mutations in CYC8 and one or more additional genes. For example, A10-1 and A10-2 both have the same CYC8 mutation (W367L) and are probably sibs for that allele, but A10-2 also has mutations in CKS1 and AIM24 (Table 1). In this case, we hypothesize that the cyc8-W367L mutation occurred early on within the culture, followed by cks1 and aim24 mutations arising in a subsequent daughter cell. There are similar examples of sequential mutations from other cultures (Table 1; A1, A3, A4, A9), suggesting that the adapted snf1∆ mutants remain mutagenic. It is possible that certain secondary mutations could further modify CLS of the adapted strains such that they gain a more competitive regrowth/survival advantage, but they are not expected to significantly impact CLS on their own because they all accompany cyc8 mutations and were never observed more than once.

–

Cyc8 as an adaptable hub for transcriptionally regulating carbon metabolism

Cyc8 as a key mediator of Snf1 function during chronological aging is especially intriguing because it contains glutamine-rich repeats (Fig. 5A) than confer the ability to form a prion known as [OCT+], a heritable amyloid-like aggregate in the cytoplasm [64]. [OCT+] as an aggregated Cyc8 protein becomes inactive and results in phenotypes similar to deleting CYC8, such as derepression of Cyc8/Tup1 repressed genes and flocculence [64]. Interestingly, the polyQ/N repeats of Cyc8 are variable between naturally occurring yeast strains, with longer repeats resulting in higher expression of Cyc8/Tup1 target genes [65]. Mutations in the glutamine-rich repeats were not identified in the adapted snf1∆ mutants, consistent with the absence of non-sense mutations that completely blocked Cyc8 function. Though it is currently unknown if [OCT+] is a CLS determinant, the frequency of [PSI+] prion formation is increased with chronological aging [66], and prion formation is also triggered by oxidative stress [67]. Perhaps [OCT+] is also triggered by oxidative stress, especially in a snf1∆ mutant. One intriguing possibility is that the TPR9 and TPR10 adaptive mutations of CYC8 protect against prion formation by promoting new physical interactions with drivers of transcription that stabilize the protein or alter association with Tup1. Given that a simple point mutation in the TPR9 repeat of Cyc8 in JS1416 shortens CLS independently of SNF1 (Fig. 5C), modulation of Cyc8 polyQ/N repeat length and aggregation could also naturally impact cell survival during quiescence.

–

The utility of adaptive regrowth as a screen for chronological aging factors

Chronological aging appears especially suited to the idea of altruistic aging, whereby programmed cell death (apoptosis) within a population of unicellular organisms benefits the survival of individual cells that are better adapted to the environment, usually due to spontaneous mutations [26]. This idea is controversial and difficult to reconcile with the more complex biology of multicellular organisms [68]. We tend to view this phenomenon in yeast as an extreme form of accelerated evolutionary selection. Cell survival in stationary phase cultures puts a strong selective pressure on the population, especially given the high ROS levels in some short-lived mutants such as snf1∆. Evidence for continual adaptation and selection within the cultures comes from the fact that we typically had to stop the quantitative CLS assays at ~14 days because the adapted snf1∆ strains that obtained cyc8 mutations would then undergo a new round of adaptation as they were chronologically aged, resulting in “gasping” again that strongly suggests selection for additional mutations. With the accessibility of multiplexed whole-genome sequencing and the small genome size of S. cerevisiae, using adaptive regrowth to identify mutations that restore longevity to short-lived mutants (such as snf1∆) is a powerful modern spin on the “old school” method of suppressor screening being applied to the problem of aging.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains, plasmids, and media

All yeast strains in this study were derived from the BY4741/BY4742 background [69] either through direct transformation or genetic crossing/tetrad dissection. Gene deletions were constructed by one-step replacement with kanMX4 PCR products, and then correct integration was confirmed by PCR from genomic DNA or colony PCR. To avoid potential mutation accumulation that could occur over time in the KO collection, we deleted and replaced one allele of SNF1 from BY4743 to generate JS1230 and then dissected tetrads. The “WT” strain JS1256 was derived from this cross and has the same genotype as the MATa KO collection strain BY4741. JS1394 and JS1399 snf1∆ haploid strains were derived from the same cross. Diploid strains E1 through E20 were generated for dominance tests by crossing JS1399 with each of the suppressor mutants (JS1413 – JS1432). We could not confirm the CYC8 deletion in the original knockout collection strain, so it was remade in JS1256 and then crossed to JS1399 to generate a heterozygous diploid JS1475. This strain was sporulated and tetrads dissected to obtain MATa cyc8∆ (JS1490) and cyc8∆ snf1∆ (JS1491) haploid strains. Genotypes are provided in Table S4. The SNF1-containing plasmid pSNF1-316 was kindly provided by Martin Schmidt [70]. Where indicated, strains were grown in rich Yeast Extract/Peptone Dextrose (YPD) or Synthetic Complete (SC) medium containing either 2% (NR) or 0.5% (CR) glucose [18]. All cell growth was at 30°C.

–

ROS and mutation frequency assays

BY4741 cell cultures were started at OD600 of 0.015 in SC medium containing either 2% or 0.5% glucose. At time points of 9, 24, and 48 hours, cell aliquots were harvested, washed with incubation buffer (10 mM MES, 100 mM KCl, 140 mM NaCl, pH6.5), and then 1×107 cells were resuspended in 1 ml of incubation buffer. Dihydrorhodamine 123 (1 mg/ml) was added to each reaction (1×107 cells/ml) to obtain a final concentration of 5 µM. Cells were incubated for 10 minutes at room temperature, and then fluorescence intensity was measured using a Spectramax plate reader at excitation 504 nm / emission 534 nm. For each condition, three biological replicates were tested and normalized to the mean signal of log phase WT NR (2% glucose) samples at a value of 1.0.

–

Spontaneous mutation of the CAN1 gene was detected by colony formation on SC medium lacking arginine and supplemented with 60 µg/ml canavanine (SC-arg+can). BY4741 was grown overnight in SC 2% glucose and then inoculated to a starting OD600 of 0.015 and allowed to grow into log phase (~0.5 OD600), the late diauxic shift (24 hr), and the early stage of stationary phase (48 hr). At each time point, cells were spread directly onto SC-arg+can plates or serially diluted with sterile water so that between 200 and 300 cells were being spread onto SC plates. Relative frequency of canavanine resistance was calculated by the ratio of canavanine-resistant colonies to total colonies on SC. The experiment was performed in biological triplicate for each condition, with three technical replicates.

–

Genetic screen for snf1∆ bypass suppressors of short CLS

The snf1∆::kanMX4 haploid strain JS1394 was streaked onto a YPD plate for single colonies from a frozen stock. One colony was then restreaked again onto YPD and 10 independent colonies (A1 through A10) were inoculated into 5 ml of SC 2% glucose media in 15 ml glass tubes with loose fitting metal caps and grown overnight while rotating in a New Brunswick Scientific roller drum at 30°C. Next, 20 µl of the overnight cultures were inoculated into 10 ml of fresh SC 2% and SC 0.5% cultures, and then incubated in the roller drum. Every 2-3 days, 20 µl aliquots were 10-fold serially diluted into sterile water, spotted onto YPD 2% agar plates, incubated for 2 days of colony growth, and photographed as previously described for qualitative CLS assays [15]. Starting at day 13 and continuing through day 17, candidate bypass suppressor colonies were picked from the YPD plates as they appeared, single colony purified, and permanently frozen as JS1413 through JS1432. Spot test growth assays on alternative carbon sources was performed by patching each strain onto a YPD plate, which was then grown overnight. The following day, cells were scraped from the patches and resuspended in 1ml of sterile water. Each sample was then normalized to an OD600 of 1.0 and 10-fold serially diluted in a 96-well plate, followed by spotting 2.5 µl onto YEP plates containing either 2% glucose, 2% ethanol/2% glycerol, or 2% potassium acetate, and incubated at 30°C. Photos were taken at day 2, 5, and 6.

–

Whole genome sequencing library preparation and analysis

Individual suppressor mutants were grown overnight in 5 ml of YPD. A YeaStar (Zymo Research) DNA kit was then used to purify genomic DNA for 1.5 ml of cells in 3 different spin columns. DNA was eluted in 60 µl of dH2O for each spin column and pooled for a total volume of 180 µl per strain. DNA was then sheared using a Diagenode Bioruptor for 45 cycles of 30 seconds “ON” and “OFF” per cycle. Sheared DNA was quantified using a Qubit fluorometer (Invitrogen) and a minimum of 1µg was used as input for NEBNext DNA library construction kit (E6040S). Libraries were prepared according to NEB guidelines and quality controlled with Agilent High Sensitivity DNA chips (5067-4626) for library size and concentration. Finalized libraries were multiplexed and sequenced on an Illumina Miseq at the UVA Genome Analysis & Technology Core Facility. Sequencing reads were mapped to the sacCer3 genome assembly using bowtie2 [71]. Samtools suite v.1.2 was used to sort and filter duplicates from the resulting bam files [72]. Genotype calls were then made with samtools mpileup while variants were called with bcftools call v.1.2. The final variant call files were modified to make them compatible with the IGV genome browser. FASTQ files for the whole genome sequencing were deposited into NCBI BioProject as accession# PRJNA396952.

–

Quantitative CLS assays

The CLS assays were performed as previously described [19]. Three single colonies of each strain were inoculated into 10 ml of SC or SC-ura media containing 2% glucose, then grown overnight while rotating in a roller drum at 30°C. A 100 µl aliquot of the overnight culture was used to inoculate a fresh SC or SC-ura culture containing either 2% or 0.5% glucose. Starting at day 2 (for SC) or day 4 (for SC-ura) 20 µl aliquots were removed and serially diluted 10-fold. 2.5 µl of the 1:10, 1:100, and 1:1000 dilutions were spotted onto YPD or SC-ura plates (for strains harboring a URA3 vector) such that 12 cultures are tested on each plate and incubated at 30°C. Photos of microcolonies growing within each spot are taken on a Nikon Eclipse 400 tetrad dissection microscope and the number of colonies counted. The fraction of cells viable at each day compared to the first day of testing (day 2 or 4) was calculated for subsequent days.

–

RT-PCR assays

JS1256, JS1394, JS1416, and JS1417 were inoculated from single colonies into 10 ml SC (2% glucose) cultures and grown overnight on the roller drum at 30°C. Fresh cultures were then inoculated to an OD600 of 0.02 in 100 ml SC (2% glucose) in 250 ml Erlenmeyer flasks. RNA isolation and quantitative RT-PCR was then performed for the CAT8, ICL1, and TFC1 genes as previously described [16]. Briefly, aliquots of the cultures were harvested at the indicated time points and total RNA isolated by the acidic phenol method [73], and then converted into cDNA using a Verso cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Scientific) according to the manufacturer instructions. Quantitative PCR was then performed using SensiMix SYBR Hi-ROX Mastermix (Bioline) on an Applied Biosystems Step-One Plus real-time PCR instrument as previously described [16]. Relative expression level for each tested gene was calculated by normalized to the control TFC1 RNA level [16]. Three biological replicates were run for each strain. The primer sequences are listed in Table 2.

–

Trehalose measurements

Yeast cultures were grown overnight in a 10 ml SC (2% glucose) culture and then re-inoculated into 50 ml SC medium (2% glucose) to A600=0.2. The cultures were then incubated shaking in a water bath. Aliquots were harvested after 5 (log phase), 24, and 48 hr, and the H2O-washed cell pellets frozen at -80°C. Trehalose was extracted from pellets (~20 mg wet weight) using the method of Parrou and Francois, which utilizes trehalase (Sigma) to convert trehalose to glucose [74]. The released glucose was then measured using a colorimetric glucose measurement kit (Sigma) with a glucose standard curve.

–

RNA-seq library construction and data analysis

Triplicate cell cultures were incubated in 10 ml of SC medium containing 2% glucose, rotating at 30°C in a roller drum. 2 ml aliquots were harvested after 6 hr (log phase) and 24 hr of growth, and the cell pellets were collected after 2 rounds of centrifugation and washing with ice cold water. RNA was then isolated from the cell pellets using the hot acid phenol method and resuspended in 50 µl of DEPC treated water [73]. Following treatment with DNase I for 15 min at 37°C, RNA concentrations were quantified using a Nanodrop 2000c spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). Libraries were constructed using NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA magnetic isolation (E7490) and NEBNext Ultra Directional II (E7760) kits with 3 µg of RNA as input. Kits were used according to manufacturer instructions, except the libraries were sized selected between 250-500 bp on a 1.5% agarose gel and gel purified using a Zymogen gel purification kit. The barcoded libraries were sequenced (75 bp single end reads) on an Illumina Nextseq 500 at the UVA Genome Analysis & Technology Core facility. Sequencing data is available at GEO (accession number GSE110409)

–

The fastq files were combined from separate lanes and mapped to the sacCer3 reference genome using bowtie2 with default options. A read counts file was obtained using a combination of bedtools multicov and a genome bed file containing all yeast ORFs. The resulting counts file was analyzed with the edgeR software package to produce a list of differentially expressed genes for all samples at 24 and 48 hours compared to log phase of the respective samples with a false discovery rate (FDR) <0.05 [75]. The list was further filtered to only include genes with reduced expression in the snf1∆ mutant compared to WT. Finally, a heatmap was produced from this list of 986 genes using the Pearson correlation clustering method with pheatmap v.0.7.7 (http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=pheatmap). Gene clusters were then examined for significant gene ontology (GO) term enrichment using Yeastmine in the Saccharomyces Genome Database [76].

References

- K. Burkewitz, Y. Zhang, and W. Mair, "AMPK at the Nexus of Energetics and Aging", Cell Metabolism, vol. 20, pp. 10-25, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2014.03.002

- M. Conrad, J. Schothorst, H.N. Kankipati, G. Van Zeebroeck, M. Rubio-Texeira, and J.M. Thevelein, "Nutrient sensing and signaling in the yeastSaccharomyces cerevisiae", FEMS Microbiology Reviews, vol. 38, pp. 254-299, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1574-6976.12065

- A. Woods, P.C. Cheung, F.C. Smith, M.D. Davison, J. Scott, R.K. Beri, and D. Carling, "Characterization of AMP-activated protein kinase beta and gamma subunits. Assembly of the heterotrimeric complex in vitro.", The Journal of biological chemistry, 1996. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8626596

- G.A. Amodeo, M.J. Rudolph, and L. Tong, "Crystal structure of the heterotrimer core of Saccharomyces cerevisiae AMPK homologue SNF1", Nature, vol. 449, pp. 492-495, 2007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature06127

- R.R. McCartney, and M.C. Schmidt, "Regulation of Snf1 Kinase", Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 276, pp. 36460-36466, 2001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M104418200

- F. Mayer, R. Heath, E. Underwood, M. Sanders, D. Carmena, R. McCartney, F. Leiper, B. Xiao, C. Jing, P. Walker, L. Haire, R. Ogrodowicz, S. Martin, M. Schmidt, S. Gamblin, and D. Carling, "ADP Regulates SNF1, the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Homolog of AMP-Activated Protein Kinase", Cell Metabolism, vol. 14, pp. 707-714, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2011.09.009

- E.M. Rubenstein, R.R. McCartney, C. Zhang, K.M. Shokat, M.K. Shirra, K.M. Arndt, and M.C. Schmidt, "Access Denied: Snf1 Activation Loop Phosphorylation Is Controlled by Availability of the Phosphorylated Threonine 210 to the PP1 Phosphatase", Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 283, pp. 222-230, 2008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M707957200

- A. Woods, M.R. Munday, J. Scott, X. Yang, M. Carlson, and D. Carling, "Yeast SNF1 is functionally related to mammalian AMP-activated protein kinase and regulates acetyl-CoA carboxylase in vivo.", The Journal of biological chemistry, 1994. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7913470

- M. Zhang, L. Galdieri, and A. Vancura, "The Yeast AMPK Homolog SNF1 Regulates Acetyl Coenzyme A Homeostasis and Histone Acetylation", Molecular and Cellular Biology, vol. 33, pp. 4701-4717, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/mcb.00198-13

- J.V. Gray, G.A. Petsko, G.C. Johnston, D. Ringe, R.A. Singer, and M. Werner-Washburne, "“Sleeping Beauty”: Quiescence inSaccharomyces cerevisiae", Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews, vol. 68, pp. 187-206, 2004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/mmbr.68.2.187-206.2004

- P. Fabrizio, and V.D. Longo, "The chronological life span of Saccharomyces cerevisiae", Aging Cell, vol. 2, pp. 73-81, 2003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1474-9728.2003.00033.x

- M. Kwolek-Mirek, and R. Zadrag-Tecza, "Comparison of methods used for assessing the viability and vitality of yeast cells", FEMS Yeast Research, pp. n/a-n/a, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1567-1364.12202

- R.W. Powers, M. Kaeberlein, S.D. Caldwell, B.K. Kennedy, and S. Fields, "Extension of chronological life span in yeast by decreased TOR pathway signaling", Genes & Development, vol. 20, pp. 174-184, 2006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gad.1381406

- B.K. Kennedy, and D.W. Lamming, "The Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin: The Grand ConducTOR of Metabolism and Aging", Cell Metabolism, vol. 23, pp. 990-1003, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2016.05.009

- D.L. Smith, Jr, J.M. McClure, M. Matecic, and J.S. Smith, "Calorie restriction extends the chronological lifespan of Saccharomyces cerevisiae independently of the Sirtuins", Aging Cell, vol. 6, pp. 649-662, 2007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00326.x

- M.B. Wierman, M. Matecic, V. Valsakumar, M. Li, D.L. Smith, S. Bekiranov, and J.S. Smith, "Functional genomic analysis reveals overlapping and distinct features of chronologically long-lived yeast populations", Aging, vol. 7, pp. 177-194, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.18632/aging.100729

- C.R. Burtner, C.J. Murakami, B.K. Kennedy, and M. Kaeberlein, "A molecular mechanism of chronological aging in yeast", Cell Cycle, vol. 8, pp. 1256-1270, 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.4161/cc.8.8.8287

- M. Matecic, D.L. Smith, X. Pan, N. Maqani, S. Bekiranov, J.D. Boeke, and J.S. Smith, "A Microarray-Based Genetic Screen for Yeast Chronological Aging Factors", PLoS Genetics, vol. 6, pp. e1000921, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1000921

- M.B. Wierman, N. Maqani, E. Strickler, M. Li, and J.S. Smith, "Caloric Restriction Extends Yeast Chronological Life Span by Optimizing the Snf1 (AMPK) Signaling Pathway", Molecular and Cellular Biology, vol. 37, 2017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/mcb.00562-16

- �. Kayikci, and J. Nielsen, "Glucose repression inSaccharomyces cerevisiae", FEMS Yeast Research, vol. 15, pp. fov068, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/femsyr/fov068

- S. Hong, and M. Carlson, "Regulation of Snf1 Protein Kinase in Response to Environmental Stress", Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 282, pp. 16838-16845, 2007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M700146200

- K. Simpson-Lavy, A. Bronstein, M. Kupiec, and M. Johnston, "Cross-Talk between Carbon Metabolism and the DNA Damage Response in S. cerevisiae", Cell Reports, vol. 12, pp. 1865-1875, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2015.08.025

- S.L. Wade, K. Poorey, S. Bekiranov, and D.T. Auble, "The Snf1 kinase and proteasome-associated Rad23 regulate UV-responsive gene expression", The EMBO Journal, vol. 28, pp. 2919-2931, 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/emboj.2009.229

- V. Longo, G. Shadel, M. Kaeberlein, and B. Kennedy, "Replicative and Chronological Aging in Saccharomyces cerevisiae", Cell Metabolism, vol. 16, pp. 18-31, 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2012.06.002

- M. Weinberger, A. Mesquita, T. Carroll, L. Marks, H. Yang, Z. Zhang, P. Ludovico, and W.C. Burhans, "Growth signaling promotes chronological aging in budding yeast by inducing superoxide anions that inhibit quiescence", Aging, vol. 2, pp. 709-726, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.18632/aging.100215

- P. Fabrizio, L. Battistella, R. Vardavas, C. Gattazzo, L. Liou, A. Diaspro, J.W. Dossen, E.B. Gralla, and V.D. Longo, "Superoxide is a mediator of an altruistic aging program in Saccharomyces cerevisiae ", The Journal of Cell Biology, vol. 166, pp. 1055-1067, 2004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1083/jcb.200404002

- W. Lo, L. Duggan, N.C. Tolga, . Emre, R. Belotserkovskya, W.S. Lane, R. Shiekhattar, and S.L. Berger, "Snf1--a Histone Kinase That Works in Concert with the Histone Acetyltransferase Gcn5 to Regulate Transcription", Science, vol. 293, pp. 1142-1146, 2001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1062322

- A. Mesquita, M. Weinberger, A. Silva, B. Sampaio-Marques, B. Almeida, C. Leão, V. Costa, F. Rodrigues, W.C. Burhans, and P. Ludovico, "Caloric restriction or catalase inactivation extends yeast chronological lifespan by inducing H 2 O 2 and superoxide dismutase activity", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 107, pp. 15123-15128, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1004432107

- M. Carlson, "Glucose repression in yeast", Current Opinion in Microbiology, vol. 2, pp. 202-207, 1999. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s1369-5274(99)80035-6

- A.A. Purmal, Y.W. Kow, and S.S. Wallace, "Major oxidative products of cytosine, 5-hydroxycytosine and 5-hydroxyuracil, exhibit sequence context-dependent mispairingin vitro", Nucleic Acids Research, vol. 22, pp. 72-78, 1994. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/22.1.72

- T.M. Malavé, and S.Y. Dent, "Transcriptional repression by Tup1–Ssn6This paper is one of a selection of papers published in this Special Issue, entitled 27th International West Coast Chromatin and Chromosome Conference, and has undergone the Journal's usual peer review process.", Biochemistry and Cell Biology, vol. 84, pp. 437-443, 2006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1139/o06-073

- M.A. Treitel, S. Kuchin, and M. Carlson, "Snf1 Protein Kinase Regulates Phosphorylation of the Mig1 Repressor in Saccharomyces cerevisiae", Molecular and Cellular Biology, vol. 18, pp. 6273-6280, 1998. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/mcb.18.11.6273

- D.W. Griggs, and M. Johnston, "Regulated expression of the GAL4 activator gene in yeast provides a sensitive genetic switch for glucose repression.", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 1991. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1924319

- J.O. Nehlin, and H. Ronne, "Yeast MIG1 repressor is related to the mammalian early growth response and Wilms' tumour finger proteins.", The EMBO journal, 1990. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2167835

- M. Papamichos‐Chronakis, T. Gligoris, and D. Tzamarias, "The Snf1 kinase controls glucose repression in yeast by modulating interactions between the Mig1 repressor and the Cyc8‐Tup1 co‐repressor", EMBO reports, vol. 5, pp. 368-372, 2004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.embor.7400120

- M. Carlson, B.C. Osmond, and D. Botstein, "Mutants of yeast defective in sucrose utilization.", Genetics, 1981. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7040163

- B.D. Patterson, S.K. Khalil, L.J. Schermeister, and M.S. Quraishi, "Plant-insect interactions. I. Biological and phytochemical evaluation of selected plants.", Lloydia, 1975. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1202312

- R.J. Rothstein, and F. Sherman, "Genes affecting the expression of cytochrome c in yeast: genetic mapping and genetic interactions.", Genetics, 1980. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6254831

- W. Song, I. Treich, N. Qian, S. Kuchin, and M. Carlson, "SSNGenes That Affect Transcriptional Repression inSaccharomyces cerevisiaeEncode SIN4, ROX3, and SRB Proteins Associated with RNA Polymerase II", Molecular and Cellular Biology, vol. 16, pp. 115-120, 1996. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.16.1.115

- A.W.R.H. Teunissen, J.A. Van Den Berg, and H. Yde Steensma, "Transcriptional regulation of flocculation genes inSaccharomyces cerevisiae", Yeast, vol. 11, pp. 435-446, 1995. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/yea.320110506

- L. D'Andrea, "TPR proteins: the versatile helix", Trends in Biochemical Sciences, vol. 28, pp. 655-662, 2003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2003.10.007

- D. Tzamarias, and K. Struhl, "Distinct TPR motifs of Cyc8 are involved in recruiting the Cyc8-Tup1 corepressor complex to differentially regulated promoters.", Genes & Development, vol. 9, pp. 821-831, 1995. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gad.9.7.821

- M.J. De Vit, J.A. Waddle, and M. Johnston, "Regulated nuclear translocation of the Mig1 glucose repressor.", Molecular Biology of the Cell, vol. 8, pp. 1603-1618, 1997. http://dx.doi.org/10.1091/mbc.8.8.1603

- M. Papamichos-Chronakis, T. Petrakis, E. Ktistaki, I. Topalidou, and D. Tzamarias, "Cti6, a PHD domain protein, bridges the Cyc8-Tup1 corepressor and the SAGA coactivator to overcome repression at GAL1.", Molecular cell, 2002. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12086626

- J.O. Westholm, N. Nordberg, E. Murén, A. Ameur, J. Komorowski, and H. Ronne, "Combinatorial control of gene expression by the three yeast repressors Mig1, Mig2 and Mig3", BMC Genomics, vol. 9, 2008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-9-601

- D. Balciunas, and H. Ronne, "Yeast genes GIS1-4: multicopy suppressors of the Gal- phenotype of snf1 mig1 srb8/10/11 cells.", Molecular & general genetics : MGG, 1999. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10628841

- F. Estruch, and M. Carlson, "Two homologous zinc finger genes identified by multicopy suppression in a SNF1 protein kinase mutant of Saccharomyces cerevisiae.", Molecular and Cellular Biology, vol. 13, pp. 3872-3881, 1993. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.13.7.3872

- M.T. Martínez-Pastor, G. Marchler, C. Schüller, A. Marchler-Bauer, H. Ruis, and F. Estruch, "The Saccharomyces cerevisiae zinc finger proteins Msn2p and Msn4p are required for transcriptional induction through the stress response element (STRE).", The EMBO journal, 1996. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8641288

- V. Haurie, M. Perrot, T. Mini, P. Jenö, F. Sagliocco, and H. Boucherie, "The Transcriptional Activator Cat8p Provides a Major Contribution to the Reprogramming of Carbon Metabolism during the Diauxic Shift in Saccharomyces cerevisiae", Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 276, pp. 76-85, 2001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M008752200

- D. Hedges, M. Proft, and K. Entian, "CAT8, a New Zinc Cluster-Encoding Gene Necessary for Derepression of Gluconeogenic Enzymes in the Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae", Molecular and Cellular Biology, vol. 15, pp. 1915-1922, 1995. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.15.4.1915

- G. Charbon, K.D. Breunig, R. Wattiez, J. Vandenhaute, and I. Noël-Georis, "Key Role of Ser562/661 in Snf1-Dependent Regulation of Cat8p in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Kluyveromyces lactis", Molecular and Cellular Biology, vol. 24, pp. 4083-4091, 2004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.24.10.4083-4091.2004

- F. Randez-Gil, N. Bojunga, M. Proft, and K. Entian, "Glucose Derepression of Gluconeogenic Enzymes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae Correlates with Phosphorylation of the Gene Activator Cat8p", Molecular and Cellular Biology, vol. 17, pp. 2502-2510, 1997. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.17.5.2502

- A. Rahner, A. Scholer, E. Martens, B. Gollwitzer, and H. Schuller, "Dual Influence of the Yeast Catlp (Snflp) Protein Kinase on Carbon Source-Dependent Transcriptional Activation of Gluconeogenic Genes by the Regulatory Gene CAT8", Nucleic Acids Research, vol. 24, pp. 2331-2337, 1996. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/24.12.2331

- P. Kyryakov, A. Beach, V.R. Richard, M.T. Burstein, A. Leonov, S. Levy, and V.I. Titorenko, "Caloric Restriction Extends Yeast Chronological Lifespan by Altering a Pattern of Age-Related Changes in Trehalose Concentration", Frontiers in Physiology, vol. 3, 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2012.00256

- L. Cao, Y. Tang, Z. Quan, Z. Zhang, S.G. Oliver, and N. Zhang, "Chronological Lifespan in Yeast Is Dependent on the Accumulation of Storage Carbohydrates Mediated by Yak1, Mck1 and Rim15 Kinases", PLOS Genetics, vol. 12, pp. e1006458, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1006458

- I. Orlandi, R. Ronzulli, N. Casatta, and M. Vai, "Ethanol and Acetate Acting as Carbon/Energy Sources Negatively Affect Yeast Chronological Aging", Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, vol. 2013, pp. 1-10, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/802870

- L. Neigeborn, and M. Carlson, "Genes affecting the regulation of SUC2 gene expression by glucose repression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae.", Genetics, 1984. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6392017

- P. Sanz, R. Viana, and M.A. Garcia-Gimeno, "AMPK in Yeast: The SNF1 (Sucrose Non-fermenting 1) Protein Kinase Complex", Experientia Supplementum, pp. 353-374, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-43589-3_14

- M. Proft, and K. Struhl, "Hog1 kinase converts the Sko1-Cyc8-Tup1 repressor complex into an activator that recruits SAGA and SWI/SNF in response to osmotic stress.", Molecular cell, 2002. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12086627

- Z. Zhang, and J.C. Reese, "Molecular Genetic Analysis of the Yeast Repressor Rfx1/Crt1 Reveals a Novel Two-Step Regulatory Mechanism", Molecular and Cellular Biology, vol. 25, pp. 7399-7411, 2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/mcb.25.17.7399-7411.2005

- B. Han, and S.D. Emr, "Phosphoinositide [PI(3,5)P2] lipid-dependent regulation of the general transcriptional regulator Tup1", Genes & Development, vol. 25, pp. 984-995, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gad.1998611

- B. Han, and S.D. Emr, "The Phosphatidylinositol 3,5-Bisphosphate (PI(3,5)P2)-dependent Tup1 Conversion (PIPTC) Regulates Metabolic Reprogramming from Glycolysis to Gluconeogenesis", Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 288, pp. 20633-20645, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M113.452813

- K.H. Wong, and K. Struhl, "The Cyc8–Tup1 complex inhibits transcription primarily by masking the activation domain of the recruiting protein", Genes & Development, vol. 25, pp. 2525-2539, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gad.179275.111

- B.K. Patel, J. Gavin-Smyth, and S.W. Liebman, "The yeast global transcriptional co-repressor protein Cyc8 can propagate as a prion", Nature Cell Biology, vol. 11, pp. 344-349, 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ncb1843

- R. Gemayel, S. Chavali, K. Pougach, M. Legendre, B. Zhu, S. Boeynaems, E. van der Zande, K. Gevaert, F. Rousseau, J. Schymkowitz, M. Babu, and K. Verstrepen, "Variable Glutamine-Rich Repeats Modulate Transcription Factor Activity", Molecular Cell, vol. 59, pp. 615-627, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2015.07.003

- S. Speldewinde, and C. Grant, "The frequency of yeast [PSI+] prion formation is increased during chronological ageing", Microbial Cell, vol. 4, pp. 127-132, 2017. http://dx.doi.org/10.15698/mic2017.04.568

-

V.A. Doronina, G.L. Staniforth, S.H. Speldewinde, M.F. Tuite, and C.M. Grant, "Oxidative stress conditions increase the frequency of de novo formation of the yeast [

PSI +] prion", Molecular Microbiology, vol. 96, pp. 163-174, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/mmi.12930 - M.V. Blagosklonny, "Program‐like aging and mitochondria: Instead of random damage by free radicals", Journal of Cellular Biochemistry, vol. 102, pp. 1389-1399, 2007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jcb.21602

- A. Leech, N. Nath, R.R. McCartney, and M.C. Schmidt, "Isolation of Mutations in the Catalytic Domain of the Snf1 Kinase That Render Its Activity Independent of the Snf4 Subunit", Eukaryotic Cell, vol. 2, pp. 265-273, 2003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/EC.2.2.265-273.2003

- B. Langmead, and S.L. Salzberg, "Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2", Nature Methods, vol. 9, pp. 357-359, 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.1923

- H. Li, B. Handsaker, A. Wysoker, T. Fennell, J. Ruan, N. Homer, G. Marth, G. Abecasis, R. Durbin, and . , "The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools", Bioinformatics, vol. 25, pp. 2078-2079, 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352

- F. Ausubel, R. Brent, R. Kingston, D. Moore, J. Seidman, J. Smith, and K. Struhl, "Current Protocols in Molecular Biology.", John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York., 2000.

- J.L. Parrou, and J. François, "A Simplified Procedure for a Rapid and Reliable Assay of both Glycogen and Trehalose in Whole Yeast Cells", Analytical Biochemistry, vol. 248, pp. 186-188, 1997. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/abio.1997.2138

- M.D. Robinson, D.J. McCarthy, and G.K. Smyth, "edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data", Bioinformatics, vol. 26, pp. 139-140, 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616

- R. Balakrishnan, J. Park, K. Karra, B.C. Hitz, G. Binkley, E.L. Hong, J. Sullivan, G. Micklem, and J. Michael Cherry, "YeastMine—an integrated data warehouse for Saccharomyces cerevisiae data as a multipurpose tool-kit", Database, vol. 2012, 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/database/bar062

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

![]() Download Supplemental Information

Download Supplemental Information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Martin Schmidt and David Auble for providing strains and plasmids, and for helpful discussions. We also thank David Auble, Patrick Grant, and Maggie Wierman for critically reading the manuscript. This work was funded in part by NIH grants GM075240 and AG053596. R.D.F. was also supported by NIH training grant GM008136.

COPYRIGHT

© 2018

Spontaneous mutations in CYC8 and MIG1 suppress the short chronological lifespan of budding yeast lacking SNF1/AMPK by Magani et al. is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.