Research Reports:

Microbial Cell, Vol. 4, No. 4, pp. 127 - 132; doi: 10.15698/mic2017.04.568

The frequency of yeast [PSI+] prion formation is increased during chronological ageing

1 University of Manchester, Faculty of Biology, Medicine and Health, The Michael Smith Building, Oxford Road, Manchester, M13 9PT, UK.

Keywords: prion, yeast, chronological ageing, autophagy.

Received originally: 03/10/2016 Received in revised form: 19/12/2016

Accepted: 13/03/2017

Published: 27/03/2017

Correspondence:

Chris M. Grant, chris.grant@manchester.ac.uk

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Shaun H. Speldewinde and Chris M. Grant (2017). The frequency of yeast [PSI+] prion formation is increased during chronological ageing. Microbial Cell 4(4): 127-132.

Abstract

Ageing involves a time-dependent decline in a variety of intracellular mechanisms and is associated with cellular senescence. This can be exacerbated by prion diseases which can occur in a sporadic manner, predominantly during the later stages of life. Prions are infectious, self-templating proteins responsible for several neurodegenerative diseases in mammals and several prion-forming proteins have been found in yeast. We show here that the frequency of formation of the yeast [PSI+] prion, which is the altered form of the Sup35 translation termination factor, is increased during chronological ageing. This increase is exacerbated in an atg1 mutant suggesting that autophagy normally acts to suppress age-related prion formation. We further show that cells which have switched to [PSI+] have improved viability during chronological ageing which requires active autophagy. [PSI+] stains show increased autophagic flux which correlates with increased viability and decreased levels of cellular protein aggregation. Taken together, our data indicate that the frequency of [PSI+] prion formation increases during yeast chronological ageing, and switching to the [PSI+] form can exert beneficial effects via the promotion of autophagic flux.

INTRODUCTION

Biological ageing involves a progressive decline in the ability of an organism to survive stress and disease. It is a complex process which is influenced by both genetic and environmental factors [1]. Common features of ageing include decreased resistance to stress, increased rates of apoptosis, a decline in autophagy and an elevated accumulation of protein aggregates [2]. In humans, ageing correlates with an increased frequency of age-related diseases including heart disease, metabolic syndromes and neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and dementia [3].

–

Prions are aberrant, infectious protein conformations which can self-replicate [4]. They are causally responsible for transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs) that cause several incurable neurodegenerative diseases in mammals [5]. The underlying cause of TSEs is the structural conversion of a soluble prion protein (PrPC) into a prion form (PrPsc) that is amyloidogenic. The amyloid form of the protein can subsequently convert other soluble molecules into the prion form thus resulting in the accumulation of the aberrant proteins in neuronal cells [6][7]. Human prion diseases are predominantly sporadic constituting approximately 70% of all cases with higher frequencies occurring during advanced age [8]. There are several prion-forming proteins in yeast with the best-characterized being [PSI+] and [PIN+], which are formed from the Sup35 and Rnq1 proteins, respectively [9][10]. [PSI+] is the altered conformation of the Sup35 protein, which normally functions as a translation termination factor during protein synthesis. The de novo formation of [PSI+] is enhanced by the presence of the [PIN+] prion, which is the altered form of the Rnq1 protein whose native protein function is unknown [11].

–

We have previously shown that autophagy protects against Sup35 aggregation and de novo [PSI+] prion formation [12]. Autophagy is an intracellular quality control pathway that degrades damaged organelles and protein aggregates via vacuolar/lysosomal degradation [13]. It proceeds in a highly sequential manner leading to the formation of a double-membrane-bound vesicle called the autophagosome. Fusion of the autophagosome with vacuoles/lysosomes introduces acidic hydrolases that degrade the contained proteins and organelles. Autophagy has been implicated in the ageing process and, for example, pharmacological interventions which induce autophagy result in lifespan extension during yeast chronological ageing [14][15]. Autophagy appears to play a protective role in the ageing process since dysregulated autophagy is implicated in the accumulation of abnormal proteins associated with several age-related diseases including Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and Huntington’s diseases [3][16][17].

–

Yeast cells can survive for prolonged periods of time in culture and have been used as a model of the chronological life span (CLS) of mammals, particularly for tissues composed of non-dividing populations [18]. Additionally, ageing is followed by replicative lifespan, which is defined as the number of budding daughter cells that originates from a particular mother yeast cell before it reaches senescence [19][20]. Given that amyloidoses are typically diseases of old-age, yeast prions might be expected to form at a higher frequency in aging yeast cells. However, a study using the yeast replicative ageing model found that ageing does not increase the frequency of prion formation [21]. In this current study we have examined [PSI+] prion formation using the yeast CLS model and found that the frequency of prion formation is increased during ageing. Furthermore, this frequency is elevated in an autophagy mutant suggesting that autophagy normally acts to suppress age-dependent prion formation. We show that the prion-status of cells influences CLS in an autophagy-dependent manner suggesting that prions can be beneficial in aged populations of yeast cells.

RESULTS

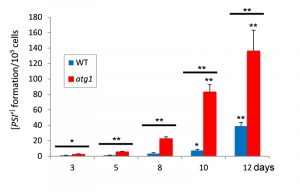

The frequency of de novo [PSI+] formation increases during chronological ageing

We examined yeast CLS to determine whether there is an increased frequency of [PSI+] appearance during ageing. Cultures were grown to stationary phase in liquid SCD media and prion formation measured over time. [PSI+] prion formation was quantified using the ade1-14 mutant allele which confers adenine auxotrophy and prions differentiated from nuclear gene mutations by their irreversible elimination in guanidine hydrochloride (GdnHCl). The frequency of de novo [PSI+] prion formation in a control [PIN+][psi–] strain grown to stationary phase was estimated to be 1.1 x 10-5 comparable to previously reported frequencies [12][22]. This frequency increased during CLS and a 39-fold increase was observed by day 12 (Fig. 1). We next examined the frequency of [PSI+] prion formation in an atg1 autophagy mutant. Atg1 is a serine/threonine kinase which is responsible for the initiation of autophagy [13][23]. The frequency of [PSI+] prion formation was further elevated in the atg1 mutant compared with a wild-type strain, suggesting that autophagy normally acts to suppress [PSI+] prion formation during ageing (Fig. 1).

[PSI+] increase longevity in a yeast CLS model

We next examined cell survival to determine whether the [PSI+] prion status of cells influences longevity. For this analysis, flow cytometry was used to monitor propidium iodide uptake to assess yeast cell death [24]. The [PIN+][PSI+] strain showed a modest increase in maximal lifespan compared with a [PIN+][psi–] strain (Fig. 2A). Additionally, cell death was lower in the [PIN+][PSI+] strain over the entire lifespan compared with the [PIN+][psi–] strain suggesting that the [PSI+] prion improves viability during ageing. To verify this difference in ageing between [PIN+][PSI+] and [PIN+][psi–] strains, viability was monitored using colony formation assays. Whilst lifespan measured using the colony forming assay was shorter compared with the propidium iodide uptake assay, it confirmed that the [PSI+] strain maintained viability longer and had an increased lifespan compared with the [psi–] strain (Fig. 2B).

Treating cells with GdnHCl blocks the propagation of most yeast prions by inhibiting the key ATPase activity of Hsp104, a molecular chaperone that is absolutely required for yeast prion propagation [25][26]. GdnHCl cures yeast cells of [PSI+] and all known prions. Curing the [PIN+][PSI+] strain with GdnHCl dramatically decreased maximal lifespan to 10 days suggesting that prions are beneficial during CLS (Fig. 2A). It should be noted however, that GdnHCl treatment can also potentially affect Hsp10-related processes which are unrelated to prions. Autophagy is known to be required for chronological longevity and for example loss of ATG1 reduces CLS [27]. Similarly, we found that loss of ATG1 reduced CLS in the 74D-694 yeast strain used for our studies (Fig. 2A). Interestingly, longevity was comparable in the [PIN+][PSI+], [PIN+][psi–] and cured strains indicating that active autophagy is required for prion-dependent effects on longevity.

–

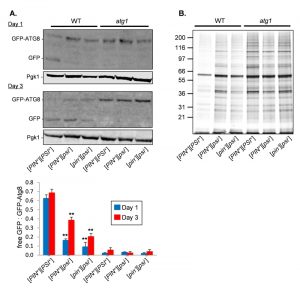

[PSI+] cells have an increased rate of autophagy and decreased concentrations of amorphous protein aggregates

Given that the [PSI+]-prion status of cells affects CLS in an autophagy-dependent manner, we examined whether autophagy is altered in [PSI+] cells. We utilized a GFP-Atg8 fusion construct to follow the autophagy-dependent proteolytic liberation of GFP from GFP-Atg8, which is indicative of autophagic flux [28]. In late exponential phase cells (day 1), more free GFP was detected in the [PIN+][PSI+] strain compared with the [PIN+][psi–] and cured [pin–][psi–] strains indicative of increased autophagic flux (Fig. 3A). By day three, there was also an increase in autophagic flux in the [PIN+][psi–] and cured [pin–][psi–] strains detected as an increase in free GFP. As expected, no autophagic activity was observed for the atg1 knockout mutants. This suggests that cells carrying the [PSI+] prion have increased autophagic activity which may be beneficial during CLS.

We next examined whether the increased autophagic activity in the [PIN+][PSI+] strain affects amorphous protein aggregation, which seemed likely given the previous studies which have suggested that autophagy plays a role in the clearance of misfolded and aggregated proteins [16][17]. For this analysis, we used a biochemical approach where we grew cells to stationary phase (day 3) and isolated aggregated proteins by differential centrifugation, and removed any contaminating membrane proteins using detergent washes [29]. The levels of protein aggregation were decreased in the [PIN+][PSI+] strain compared with the [PIN+][psi–] and cured [pin–][psi–] strains (Fig. 3B). This reduction in protein aggregation required autophagy since the levels of protein aggregation were comparable in the atg1-mutant version strains.

DISCUSSION

The majority of prion disease cases in humans occur in a sporadic manner, predominantly manifesting during later stages of life [8]. Similarly, we found an age-dependent increase in the frequency of de novo [PSI+] formation during yeast chronological ageing, with the frequency of spontaneous formation increased approximately 40-fold in aged cells. Yeast has emerged as a powerful model to investigate the stochasticity of the ageing process and its contributing factors. The yeast CLS model more closely resembles the ageing of non-dividing cells such as neurons [18]. Neuronal cells are post-mitotic in nature and rely on proteostasis mechanisms such as autophagy to facilitate the elimination of superfluous and damaged material. The age-dependent increase in the de novo formation of [PSI+] was exacerbated in an atg1 mutant suggesting that autophagy normally acts to suppress spontaneous prion formation during chronological ageing. Similarly, loss of autophagy has been found to cause neurodegenerative diseases in mice [16][17], supporting a protective role for autophagy in defending against age-associated abnormal protein accumulation and aggregation.

–

We found that that the presence of the [PSI+] prion confers a beneficial advantage during yeast chronological ageing, which correlates with enhanced autophagic flux. Given that the [PSI+]-status of cells improves viability during ageing, this may result in selection for [PSI+] in aged cells. Our data indicate that the presence of the [PSI+] prion acts to simulate autophagy which results in improved viability during ageing. There is previous evidence to suggest that the increased formation and accumulation of protein aggregates may exert a stimulatory effect on the autophagy pathway. For example, there is a correlation between the accumulation of PrPSC and the enhanced activity of quality control pathways including endoplasmic reticulum chaperones, the unfolded protein response and autophagy [30]. In agreement with the idea that enhanced autophagy aids protein homeostasis during ageing, we found reduced levels of amorphous protein aggregation in a [PSI+] strain, suggesting that autophagy provides a beneficial effect during chronological ageing by removing potentially harmful protein aggregates, including both amorphous and amyloid forms. Increasing autophagic flux would also presumably act to prevent further amyloid aggregation, potentially protecting against any negative impact of [PSI+] aggregation altering translation termination efficiency.

–

The [PSI+] prion causes a loss of function phenotype where translation termination activity is reduced due to the aggregation of the normally soluble Sup35 protein [10]. The shift to the [PSI+] prion is thought to allow cells to reprogram gene expression such that new genetic traits become uncovered which may aid survival during altered conditions [31][32][33]. However, as well as providing a selective advantage through altered gene expression, our data indicate that the [PSI+] prion can improve viability during ageing via modulation of autophagic flux. It is unclear what triggers the increased frequency of [PSI+] prion formation during ageing. One possibility is oxidative stress, since ROS-induced protein aggregation and mitochondrial dysfunction is a common feature in age-related diseases [34][35]. In addition, ROS and oxidative stress are known to induce yeast and mammalian prion formation [36] which may account for increased [PSI+] formation observed during chronological ageing. Further research will be required to elucidate the exact signaling pathways and the range of quality control mechanisms that may be modulated through the direct and indirect action of the [PSI+] prion during yeast ageing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast Strains

[PIN+][PSI+], [PIN+][psi−] and [pin–][psi−] derivatives of the wild-type yeast strain 74D-694 (MATa ade1-14 ura3-52 leu2-3,112 trp1-289 his3-200) were used for all experiments. The strain deleted for ATG1 (atg1::HIS3) has been described previously [12].

–

Growth conditions

Yeast strains were grown at 30°C, 180 rpm in minimal SCD medium (2% w/v glucose, 0.17% yeast nitrogen base without amino acids, supplemented with Kaiser amino acid mixes, Formedium, Hunstanton, England). Chronological life span experiments were performed in liquid SCD media supplemented with a four-fold excess of uracil, leucine, tryptophan, adenine and histidine to avoid any possible artefacts arising from the auxotrophic deficiencies of the strains. Strains were cured by five rounds of growth on YEPD agar plates containing 4 mM GdnHCl.

–

De novo [PSI+] formation

[PSI+] prion formation was scored by growth in the absence of adenine as described previously [12]. [PSI+] formation was calculated based on the mean of at least three independent biological repeat experiments.

–

Yeast Chronological Life Span Determination

CLS experiments were performed according to [37]. Briefly, cells were cultured in liquid SCD media for 3 days to reach stationary phase and then aliquots taken every 2-3 days for flow cytometry analysis. 50 µl of 4 mM of propidium iodide (P.I.) was added to 950 µl of culture and cell viability was measured based on propidium iodide uptake by non-viable cells as assayed through flow cytometry. Flow cytometry readings were performed using a Becton Dickinson (BD) LSRFortessa™ cell analyser, BD FACSDiva 8.0.1 software) after staining with propidium iodide. For the colony forming assay, cultures were serially diluted and plated onto YEPD plates. Viable counts were recorded following three days growth and were expressed as a percentage of the starting viability.

–

Protein analysis

Protein extracts were electrophoresed under reducing conditions on SDS-PAGE minigels and electroblotted onto PVDF membrane (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Bound antibody was visualised using WesternSure® Chemiluminescent Reagents (LI-COR) and a C-DiGit® Blot Scanner (LI-COR). Insoluble protein aggregates were isolated as previously described [38][39], with the following minor adjustments [29]. Cell breakage was achieved by sonication (Sonifier 150, Branson; 8 x 5 s, Level 4) and samples were adjusted to equal protein concentrations before isolation of protein aggregates. Insoluble fractions were resuspended in detergent washes through sonication (4 x 5 s, Level 4). Insoluble fractions were resuspended in reduced protein loading buffer, separated by reducing SDS/PAGE (12% gels) and visualized by silver staining with the Bio-Rad silver stain plus kit. The induction of autophagy was confirmed by examining the release of free GFP due to the proteolytic cleavage of GFP-Atg8 [28].

References

- C.J. Kenyon, "The genetics of ageing", Nature, vol. 464, pp. 504-512, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature08980

- B. Levine, and G. Kroemer, "Autophagy in the Pathogenesis of Disease", Cell, vol. 132, pp. 27-42, 2008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.018

- D. Rubinsztein, G. Mariño, and G. Kroemer, "Autophagy and Aging", Cell, vol. 146, pp. 682-695, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.030

- S.B. Prusiner, "Prions.", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 1998. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9811807

- A. Aguzzi, and T. O'Connor, "Protein aggregation diseases: pathogenicity and therapeutic perspectives", Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, vol. 9, pp. 237-248, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrd3050

- J. Collinge, and A.R. Clarke, "A General Model of Prion Strains and Their Pathogenicity", Science, vol. 318, pp. 930-936, 2007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1138718

- S.B. Prusiner, "Biology and Genetics of Prions Causing Neurodegeneration", Annual Review of Genetics, vol. 47, pp. 601-623, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-genet-110711-155524

- B.S. Appleby, and C.G. Lyketsos, "Rapidly progressive dementias and the treatment of human prion diseases", Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy, vol. 12, pp. 1-12, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1517/14656566.2010.514903

- I.L. Derkatch, M.E. Bradley, P. Zhou, Y.O. Chernoff, and S.W. Liebman, "Genetic and environmental factors affecting the de novo appearance of the [PSI+] prion in Saccharomyces cerevisiae.", Genetics, 1997. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9335589

- R.B. Wickner, "[URE3] as an Altered URE2 Protein: Evidence for a Prion Analog in Saccharomyces cerevisiae", Science, vol. 264, pp. 566-569, 1994. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.7909170

- S. Treusch, and S. Lindquist, "An intrinsically disordered yeast prion arrests the cell cycle by sequestering a spindle pole body component", Journal of Cell Biology, vol. 197, pp. 369-379, 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1083/jcb.201108146

- S.H. Speldewinde, V.A. Doronina, and C.M. Grant, "Autophagy protects against de novo formation of the [PSI+] prion in yeast", Molecular Biology of the Cell, vol. 26, pp. 4541-4551, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1091/mbc.E15-08-0548

- K.R. Parzych, and D.J. Klionsky, "An Overview of Autophagy: Morphology, Mechanism, and Regulation", Antioxidants & Redox Signaling, vol. 20, pp. 460-473, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/ars.2013.5371

- T. Eisenberg, H. Knauer, A. Schauer, S. Büttner, C. Ruckenstuhl, D. Carmona-Gutierrez, J. Ring, S. Schroeder, C. Magnes, L. Antonacci, H. Fussi, L. Deszcz, R. Hartl, E. Schraml, A. Criollo, E. Megalou, D. Weiskopf, P. Laun, G. Heeren, M. Breitenbach, B. Grubeck-Loebenstein, E. Herker, B. Fahrenkrog, K. Fröhlich, F. Sinner, N. Tavernarakis, N. Minois, G. Kroemer, and F. Madeo, "Induction of autophagy by spermidine promotes longevity", Nature Cell Biology, vol. 11, pp. 1305-1314, 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ncb1975

- A.L. Alvers, M.S. Wood, D. Hu, A.C. Kaywell, W.A. Dunn, Jr., and J.P. Aris, "Autophagy is required for extension of yeast chronological life span by rapamycin", Autophagy, vol. 5, pp. 847-849, 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.4161/auto.8824

- M. Komatsu, S. Waguri, T. Chiba, S. Murata, J. Iwata, I. Tanida, T. Ueno, M. Koike, Y. Uchiyama, E. Kominami, and K. Tanaka, "Loss of autophagy in the central nervous system causes neurodegeneration in mice", Nature, vol. 441, pp. 880-884, 2006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature04723

- T. Hara, K. Nakamura, M. Matsui, A. Yamamoto, Y. Nakahara, R. Suzuki-Migishima, M. Yokoyama, K. Mishima, I. Saito, H. Okano, and N. Mizushima, "Suppression of basal autophagy in neural cells causes neurodegenerative disease in mice", Nature, vol. 441, pp. 885-889, 2006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature04724

- V. Longo, G. Shadel, M. Kaeberlein, and B. Kennedy, "Replicative and Chronological Aging in Saccharomyces cerevisiae", Cell Metabolism, vol. 16, pp. 18-31, 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2012.06.002

- B.M. Wasko, and M. Kaeberlein, "Yeast replicative aging: a paradigm for defining conserved longevity interventions", FEMS Yeast Research, vol. 14, pp. 148-159, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1567-1364.12104

- R.K. MORTIMER, and J.R. JOHNSTON, "Life Span of Individual Yeast Cells", Nature, vol. 183, pp. 1751-1752, 1959. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/1831751a0

- F. Shewmaker, and R.B. Wickner, "Ageing in yeast does not enhance prion generation", Yeast, vol. 23, pp. 1123-1128, 2006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/yea.1425

- A.K. Lancaster, J.P. Bardill, H.L. True, and J. Masel, "The Spontaneous Appearance Rate of the Yeast Prion [PSI+] and Its Implications for the Evolution of the Evolvability Properties of the [PSI+] System", Genetics, vol. 184, pp. 393-400, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1534/genetics.109.110213

- A. Matsuura, M. Tsukada, Y. Wada, and Y. Ohsumi, "Apg1p, a novel protein kinase required for the autophagic process in Saccharomyces cerevisiae", Gene, vol. 192, pp. 245-250, 1997. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00084-x

- Y. Pan, E. Schroeder, A. Ocampo, A. Barrientos, and G. Shadel, "Regulation of Yeast Chronological Life Span by TORC1 via Adaptive Mitochondrial ROS Signaling", Cell Metabolism, vol. 13, pp. 668-678, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2011.03.018

- G. Jung, and D.C. Masison, "Guanidine Hydrochloride Inhibits Hsp104 Activity In Vivo: A Possible Explanation for Its Effect in Curing Yeast Prions", Current Microbiology, vol. 43, pp. 7-10, 2001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s002840010251

- P.C. Ferreira, F. Ness, S.R. Edwards, B.S. Cox, and M.F. Tuite, "The elimination of the yeast [PSI+] prion by guanidine hydrochloride is the result of Hsp104 inactivation", Molecular Microbiology, vol. 40, pp. 1357-1369, 2001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02478.x

- A.L. Alvers, L.K. Fishwick, M.S. Wood, D. Hu, H.S. Chung, W.A. Dunn Jr, and J.P. Aris, "Autophagy and amino acid homeostasis are required for chronological longevity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae", Aging Cell, vol. 8, pp. 353-369, 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00469.x

- T. Noda, A. Matsuura, Y. Wada, and Y. Ohsumi, "Novel System for Monitoring Autophagy in the Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae", Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, vol. 210, pp. 126-132, 1995. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/bbrc.1995.1636

- A.J. Weids, and C.M. Grant, "The yeast Tsa1 peroxiredoxin protects against protein aggregate-induced oxidative stress", Journal of Cell Science, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1242/jcs.144022

- S. Joshi-Barr, C. Bett, W. Chiang, M. Trejo, H.H. Goebel, B. Sikorska, P. Liberski, A. Raeber, J.H. Lin, E. Masliah, and C.J. Sigurdson, "De Novo Prion Aggregates Trigger Autophagy in Skeletal Muscle", Journal of Virology, vol. 88, pp. 2071-2082, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.02279-13

- J. Tyedmers, M.L. Madariaga, and S. Lindquist, "Prion Switching in Response to Environmental Stress", PLoS Biology, vol. 6, pp. e294, 2008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.0060294

- H.L. True, and S.L. Lindquist, "A yeast prion provides a mechanism for genetic variation and phenotypic diversity", Nature, vol. 407, pp. 477-483, 2000. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/35035005

- H.L. True, I. Berlin, and S.L. Lindquist, "Epigenetic regulation of translation reveals hidden genetic variation to produce complex traits", Nature, vol. 431, pp. 184-187, 2004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature02885

- J.J. Shacka, "The autophagy-lysosomal degradation pathway: role in neurodegenerative disease and therapy", Frontiers in Bioscience, vol. 13, pp. 718, 2008. http://dx.doi.org/10.2741/2714

- J. Lee, S. Giordano, and J. Zhang, "Autophagy, mitochondria and oxidative stress: cross-talk and redox signalling", Biochemical Journal, vol. 441, pp. 523-540, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1042/BJ20111451

- C.M. Grant, "Sup35 methionine oxidation is a trigger forde novo[PSI+] prion formation", Prion, vol. 9, pp. 257-265, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19336896.2015.1065372

- A. Ocampo, and A. Barrientos, "Quick and reliable assessment of chronological life span in yeast cell populations by flow cytometry", Mechanisms of Ageing and Development, vol. 132, pp. 315-323, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mad.2011.06.007

- J.D. Rand, and C.M. Grant, "The Thioredoxin System Protects Ribosomes against Stress-induced Aggregation", Molecular Biology of the Cell, vol. 17, pp. 387-401, 2006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1091/mbc.E05-06-0520

- T. Jacobson, C. Navarrete, S.K. Sharma, T.C. Sideri, S. Ibstedt, S. Priya, C.M. Grant, P. Christen, P. Goloubinoff, and M.J. Tamás, "Arsenite interferes with protein folding and triggers formation of protein aggregates in yeast", Journal of Cell Science, 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1242/jcs.107029

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

S.H.S. was supported by a Wellcome Trust (grant number 099733/Z/12/Z) funded studentship.

COPYRIGHT

© 2017

The frequency of yeast [PSI+] prion formation is increased during chronological ageing by Shaun H. Speldewinde and Chris M. Grant is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.