Reviews:

Microbial Cell, Vol. 3, No. 9, pp. 476 - 490; doi: 10.15698/mic2016.09.530

HPV disease transmission protection and control

The Jake Gittlen Laboratories for Cancer Research, Penn State College of Medicine, 500 University Drive, Hershey, PA 17033, USA.

Keywords: HPV, animal papillomaviruses, pathogenesis, vaccines, immunotherapy, viral oncogenesis, codon modification.

Received originally: 27/02/2016 Received in revised form: 21/05/2016

Accepted: 30/05/2016

Published: 05/09/2016

Correspondence:

Neil D. Christensen, The Jake Gittlen Laboratories for Cancer Research, Penn State College of Medicine, 500 University Drive, Hershey, PA 17033, USA waipu6514@gmail.com

Conflict of interest statement: I declare no conflict of interest in the preparation of this work.

Please cite this article as: Neil D. Christensen (2016). HPV disease transmission protection and control. Microbial Cell 3(9): 475-489.

Abstract

Human papillomaviruses (HPVs) represent a large collection of viral types associated with significant clinical disease of cutaneous and mucosal epithelium. HPV-associated cancers are found in anogenital and oral mucosa, and at various cutaneous sites. Papillomaviruses are highly species and tissue restricted, and these viruses display both mucosotropic, cutaneotropic or dual tropism for epithelial tissues. A subset of HPV types, predominantly mucosal, are also oncogenic and cancers with these HPV types account for more than 200,000 deaths world-wide. Host control of HPV infections requires both innate and adaptive immunity, but the viruses have developed strategies to escape immune detection. Viral proteins can disrupt both innate pathogen-sensing pathways and T-cell based recognition and subsequent destruction of infected tissues. Current treatments to manage HPV infections include mostly ablative strategies in which recurrences are common and only active disease is treated. Although much is known about the papillomavirus life cycle, viral protein functions, and immune responsiveness, we still lack knowledge in a number of key areas of PV biology including tissue tropism, site-specific cancer progression, codon usage profiles, and what are the best strategies to mount an effective immune response to the carcinogenic stages of PV disease. In this review, disease transmission, protection and control are discussed together with questions related to areas in PV biology that will continue to provide productive opportunities of discovery and to further our understanding of this diverse set of human viral pathogens.

INTRODUCTION

Papillomaviruses are an ancient group of viruses exquisitely adapted to their hosts in a tissue and species-restricted manner (reviewed in [1][2]). The human papillomaviruses (HPVs) are responsible for significant morbidity and mortality in the form of various epithelial infections and cancers of skin, anogenital and oral sites (reviewed in [3][4][5][6][7]). Classification and evolutionary analyses of sequenced genomes suggest that expansion of new PV types from a primordial type began with the appearance of hair and skin glands in ancestral mammals over 200 million years ago [8]. Today, species-specific PVs can be found in most mammals, birds and in several reptiles such as the chelonians and snakes [9]. In humans, over 150 types have been fully sequenced [10], with another 200 different HPV genotypes partially sequenced and many more likely yet to be discovered [11]. HPV infections are both ubiquitous and common in humans and it is fortunate for us all that most of these infections are benign, clinically asymptomatic and controlled by host adaptive immunity. Currently, approximately 15 different HPV types labeled as high-risk HPV (hrHPV) have been clearly associated with epithelial cancers [12]. An additional limited number of types are suspected of having carcinogenic potential [12][13]. When viewed collectively, all papillomaviruses share several conserved features including:

- A small double-stranded DNA genome of around 8Kb, in which numerous viral RNA species are transcribed from one strand only, many of which are represented as multiple spliced transcripts [10].

- A region containing early genes (usually represented by 5-6 proteins).

- A region containing two late genes coding for the capsid proteins.

- A non-coding region containing regulatory elements and a replication origin.

–

Current control of HPV infections is focused on preventive strategies via induction of neutralizing antibodies; by various ablative strategies for lesion removal, and attempts to activate antigen-specific cell-mediated immunity (reviewed in [14]). Questions arise as to why a limited number of these many HPV types progress to malignancy. A combination of immune escape strategies and oncogenic potential of these select types seems the most likely scenario. Many HPV types produce minimal disease and can be best characterized as commensal flora of the skin and mucosa [15]. Another important issue related to host control of HPV infections is whether the infectious HPV “load” present in almost all members of the population generates a mild immune-tolerized state due to the commonness of these viral infections. An alternative hypothesis is that these viruses are predominantly immune “invisible” due to viral immune escape mechanisms and lack of inflammatory events in situ.

–

Despite current prophylactic vaccines and other treatment strategies, these viruses continue to be a significant health hazard and also a fascinating group of viruses to whet our appetite for new knowledge on keratinocyte biology, viral oncogenesis, viral tissue restriction and viral evolution. In this review we present an overview of PV biology and propose a series of questions that provide a basis for discussion of some areas of interest that continue to represent important gaps in our knowledge in the HPV research field.

ETIOLOGY, TRANSMISSION AND PROTECTION

Questions relevant to this section:

- Have we found “all” the different HPV types? What would be the predicted number based on current data sets and extrapolation, and are new HPV types continuing to evolve?

- Have we identified all viral proteins/products produced by papillomaviruses during their life cycle? Are there any viral miRNA species yet to be discovered?

- How do new types appear over evolutionary time?

- At what age do infants become infected with HPV? Is there in utero transmission?

- How does the adaptive immune system detect HPV infections in the absence of inflammation?

- Are there sites of infections in patients that show or develop differential immune privilege that allow for increased localized persistence?

- What innate immune escape strategies utilized by PVs are yet to be discovered?

- Will vaccination against a restricted set of HPV types lead to replacement with vaccine-unrelated HPV types? Will vaccines accelerate evolutionary changes in vaccine-matched HPV types or elimination of these types?

–

HPV types currently number more than 150 genotypes that have been fully sequenced [10]. Papillomavirus researchers have settled on a definition of an HPV type in which a 10% difference in the base sequence of the L1 gene with all existing HPV types is required to define a new type [9][16]. Equivalent classification systems can also be developed from sequence comparisons of the viral E6 oncogene, although, interestingly, these methods do not always yield congruent results [17]. Intriguingly, there appear to be still many new HPV types yet to be detected as demonstrated by recent analyses on tissue samples using deep-sequencing techniques [11]. These new HPV types await further characterization and full sequencing. Classification of papillomaviruses [10] show many different clades or groupings of PVs in which the HPVs are segregated into 3 main groups including Alphapapillomaviruses (mostly mucosotropic), Betapapillomaviruses (mostly cutaneous) and Gammapapillomaviruses (HPVs that include types that can be found in both cutaneous and mucosal sites). When viewed collectively, there remain additional HPV types in other subgroups that are genetically aligned with different animal papillomavirus types.

–

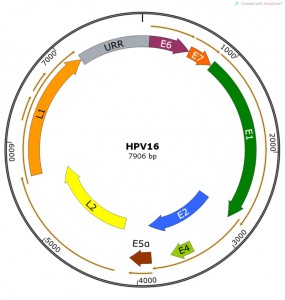

| FIGURE 1: HPV16 genome showing viral open reading frames coding for known viral pro-teins. The Upstream Regulatory Region (URR) is shown in grey. Map constructed using SnapGene software. |

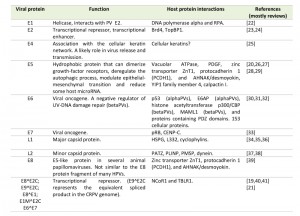

PV genomes are approximately 8000 bps of double-stranded DNA with ORFs coding for early (E) and late (L) proteins. ORFs have been identified from the coding sequence for E1, E2, E4, E5, E6 and E7 early proteins and L1 and L2 late proteins (Table 1, Figure 1). Confirmation as to whether additional viral proteins are present (or confirmation that we have now identified “all” PV proteins) are challenging experiments to conduct yet several potential reading frames (e.g. E3, E9, E10, L3) remain unstudied and therefore are assumed to be non-functional and/or non-essential. Spliced viral RNA species have been mapped and “new” proteins (e.g. E8^E2) have been confirmed by studies in an animal papillomavirus model [18] which is amenable to mutational studies. This new protein was later confirmed to be functional in most HPV types [19]. Given the smallness of the E5 ORF and the redundant functional activities of hydrophobic E5-like proteins [20] we should be encouraged to continue more systematic analysis of other small uncharacterized ORFs and understudied spliced proteins (e.g. E6^E7 [21]) in PV genomes. It is well-recognized in other virus systems that there are many viral proteins that operate as host restriction factors and/or immune function modulators that can be confirmed only by studies using in vivo models.

–

| TABLE 1. Papillomavirus proteins and functions. [19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41] |

HPV infections are believed to occur following wounding of epithelium and subsequent infectious virion access to basal epithelial cells and basement membrane components of the epithelium (reviewed in [1]). Enhanced infection following wounding has been confirmed experimentally in preclinical models [22][23]. Current diagrams often depict virions entering a breach in the epithelium whereby free virions reach the basal cells and initiate infections. PV-associated lesions are then maintained via persistence of viral-infected basal cells and the lesions increase in mass via replication of infected cells coupled with epithelial differentiation. Vertical maturation of infected keratinocytes completes the virus life cycle culminating in virion assembly in the upper layers of the wart. Natural transmission of cutaneous infections likely involves physical contact of the upper keratinized wart with normal skin generating microabrasions allowing virus-containing squames to be shed into the wounded site. Environmental contact between virus-laden shed squames and skin surface wounds are also a likely transmission mechanism. Virion release from the squames may include a combination of keratin filament disassembly events involving viral E4 proteins [24], and host/microbial proteases [25] with subsequent release of the cell-free virions into the wounded site. Mucosal infections are also believed to occur following mechanical wounding during sexual intercourse for vaginal and anal infections.

–

A question arises as to whether virions can access basal cells via a retro-transport mechanism in areas of epithelial “conflict” at what are known as transition zones located in the cervix and anal canal [26]. Cell culture experiments have demonstrated that virions can bind to cellular filopodia and subsequently be retro-transported significant distances [27] suggesting possible cell-to-cell or cell-to-ECM (extracellular matrix) transfer [28][29] that would bypass the need for direct wounding. Other viruses use a similar strategy of cell-cell transfer and epithelial basement membrane interactions (reviewed in [25]). The transition zone sites [30] are particularly vulnerable to persistent HPV infections that can lead to malignant progression [26][31]. A mechanism to describe the selectivity and exclusivity of entry of HPV virions into these unique sites is not easy to reconcile with the general concept of transmission via site-specific mechanical damage during sexual intercourse.

–

Natural protection and control of HPV infections

Papillomaviruses have developed a variety of strategies to escape host innate and adaptive immunity (reviewed in [32][33]). A central tenet for the failure of immune control and detection is the lack of inflammatory events during the various stages of infection. PV infections are confined to epithelial tissues and are highly localized. Several viral proteins are involved in immune escape (Table 1), including: (i) E5, which can down-regulate MHC Class I and other key molecules in the antigen-presentation pathways [34][35]; (ii) E6 and E7, which can suppress host interferon pathways [36][37][38], activate the DNA-damage pathways [39][40][41], and induce immune suppression via activation of suppressive cytokines and Tregs [42][43].

–

Clear evidence for immune control stems from studies on preclinical models [44] and immunosuppressed patients [45][46][47]. In the preclinical cottontail rabbit PV (CRPV) model, two natural CRPV variants exist in which one variant is poorly immunogenic and produces persistent infections whereas the second variant is immunogenic and easily cleared by host immunity [48]. Several amino acid differences in the E6 protein alone altered the persistor strain to an immunogenic or regressive phenotype [49]. Interestingly, when the rabbits were immunosuppressed prior to infection with the regressive variant then subsequently released from immunosuppression, persistent lesions were observed in some (but not all) animals [50]. These preclinical results support similar observations in immunosuppressed patients where persistent HPV infections are prevalent and can expand to clinical disease during immunosuppression [45]. The implications of these studies are that HPV infections may develop into persistent infections following immune depression arising via temporary environmental stresses. Thus, under normal immunocompetent conditions these infections would have been cleared effectively.

–

Host restriction factors

The exquisite tissue restriction of some HPVs has attracted recent interest in the “new” fields of viral-host interactions in which various host restriction factors influence virus life cycles [51]. Some recent observations in HPV in vitro models indicate roles for APOBEC3 family members [52][53], DNA-damage repair (DDR) pathways [39][40][41], IFN-kappa [54][55], IFI16 [56], TLR9 [57][58] and IL1β [59][60] as host restriction factors or pathways that the virus must overcome. Recent studies on the DNA sensor, IFI16, suggested that the proposed editing of HPV in cervical cancer may be linked to HPV-mediated induction of a human APOBEC3-dependent intrinsic host defense mechanism [56]. DDR pathway activation and suppression occurs in HPV replication and carcinogenesis mediated by viral E1 and E2 (repression) and viral E6 and E7 (activation) respectively [41].

–

New observations on the role of HPV in autophagy also demonstrate host-mediated control pathways disrupted by HPV [61][62][63]. Finally, there are potential impacts on HPV infection via host microRNA [64][65]. Recent studies have begun to search for various miRNA species as markers for HPV-associated cervical and oral cancers and precancers (reviewed in [66][67]). Collectively, these areas of research will continue to provide a fruitful avenue of new observations in improving our understanding of host control of HPV infection and carcinogenesis.

–

Innate and adaptive immune modulators

Potential innate and adaptive immune control of PV infections must be thwarted by these viruses in order to complete their life cycle. At the same time, the virus must use many host factors and the host replication machinery for completion of their life cycle. Studies show that central adaptive immune control of HPV infections is by type-1 interferon (IFN) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α cytokine-producing T cells [68]. Down-regulation of interferon pathways is a common virus escape mechanism, and HPVs can accomplish innate immune evasion by augmenting the expression of interferon-related developmental regulator 1 (IFRD1) in an EGFR-dependent manner [69]. In addition, the E7 protein of hrHPV has been shown to bind HDAC1 and prevent acetylation of histones, thereby suppressing signaling from the innate immune sensor, TLR9 [57]. Codon usage has also been hypothesized to alter immune detection and responsiveness to different HPV classes [70]. A better understanding of these various immune escape strategies will be needed to improve immunotherapeutic approaches to HPV management.

PATHOLOGY/SYMPTOMATOLOGY

Questions relevant to this section:

- Why do infections with some HPV types manifest only as asymptomatic disease whereas others show active clinical disease?

- Why do infections by different HPV types progress to cancer whereas others do not?

- Do HPV16-associated cancers at different anatomical locations have a similar pathology, etiology, and progression rate?

- Are HPV-associated cancers less immunogenic (or have differences in immune escape mechanisms) than precancerous or primary benign HPV infections of the same HPV type?

- Does the detection of HPV viral DNA correlate 100% with active clinical disease?

–

HPV infections present as epithelial lesions that are localized to cutaneous or mucosal sites. All cutaneous tissues are susceptible to HPV infections although mucosal infections are mostly confined to the anogenital and oral cavities as well as laryngeal epithelium. Other less common mucosal sites include bladder, conjunctiva and lung epithelium. The infections range from asymptomatic infections (particularly from the beta- gammapapillomaviruses) to small epithelial lesions to very large cutaneous lesions to large cancerous lesions. In general, most infections are small in size, and present with minimal evidence of infection (no fever, rash, itchiness or any other signs of discomfort).

–

Many HPV infections are confirmed by sensitive DNA detection methods rather than via histological or in situ analyses. Those HPV types that produce asymptomatic disease are challenging to locate in situ. That these asymptomatic infections are true infections that complete the virus life cycle and release infectious virions is absolutely confirmed by the existence and persistence of these many HPV types in patient populations.

–

One HPV type (HPV16) stands out as highly associated with cancers at several different anatomical locations (cervix, penis, anus, oropharynx, and other rare sites such as the esophagus [71] and bladder [72][73]). These lesions have been examined extensively for various diagnostic markers and yet the reasons for differential progression rates and susceptibility of the various sites remain unclear. We also do not yet know whether the innate and adaptive immune systems respond differently to HPV infections at these different anatomical locations. Another unknown is the potential differential immune response to oncogenic HPV infections at the early benign/precancerous stage versus the later carcinomatous stage. There may be enhanced immune escape mechanisms in play in the latter cases that allow a site-specific cancer to eventuate. Also complicating the issue is that there are now a number of different HPV16 subtypes and mutants with differing levels of infection and progression rates in different patient populations [74].

–

The primary oncogenic potential of HPV types resides in 3 major viral proteins, E5, E6 and E7 [20][75][76][77]. For hrHPV types in the alphapapillomavirus group, extensive in vitro studies and transgenic animal models have confirmed the oncogenic potential of E6 and E7 proteins [78][79][80][81][82][83]. Oncogenic activities of the E6 and E7 proteins includes p53 sequestration, pRB binding, interference with DNA damage response pathways, disruption of cell cycle and cell division pathways, and immune evasion (reviewed in [5][33][84]). An oncogenic role for some betapapillomaviruses such as HPV5 and HPV8 includes important co-factors such as UV-damage and include p53 modulation [47][85]. Untreated HPV-associated cancers can progress to malignant cancers that are locally invasive, difficult to treat, and often lead to death of the host. New pathways for transformation are continuing to be identified (e.g. role of autophagy [86]). There is a generalized assumption that malignancies in different anatomical locations initiated by the same HPV type are similar mechanistically. As mentioned previously, we are likely to find both unifying and unique molecular and cellular events when studying HPV16 (and their variants) infections of the cervix, vagina, penis, anus and oral cavity.

–

HPV types that infect skin show different histopathology when compared with HPV types that infect the mucosa. Notably, differences in the impact of the viral E4 protein expression lead to phenotypic uniqueness of infections by alpha- versus betapapillomaviruses [87]. The high production of the E4 protein in the lesions can be used as a diagnostic marker for various HPV diseases [88][89]. New biomarkers are continuing to be discovered and continue to be needed to assist clinical diagnoses, assess treatment outcomes, and to inform physicians as to the appropriate management and treatment of HPV disease.

EPIDEMIOLOGY, INCIDENCE AND PREVALENCE

Questions relevant to this section:

- Have we discovered all the risk-factors associated with HPV progression and cancers?

- What viral and host factors (gender, race, age and anatomical site) are associated with a potential differential susceptibility to HPV infections.

- Given the commensal nature of some skin and mucosotropic HPV and their prevalence, do these commensal infections provide a potential localized immune tolerance for subsequent infection by the more pathogenic HPVs thereby reducing the initial host immune response to these latter types?

- Is there competition or synergistic interactions between different HPV types during a co-infection?

- Do asymptomatic HPV infections trigger protective homeostatic host immunity to these and other common skin microbes? Do other microbes at skin and mucosal sites provide immune “cover” for many asymptomatic HPV infections?

- Is there a correlation between codon usage profiles and tissue tropism for HPV types?

–

HPVs are one of the most ubiquitous viral infections with over 300 viral types that infect most cutaneous and many mucosal tissues. Most types are associated with minimal disease and can be described as part of the commensal fauna of these tissues. Numerous epidemiological and molecular studies on cervical cancer demonstrate that hrHPV are associated with up to 99% with cervical cancers [3][14]. This near 100% association between an infectious agent and a particular cancer is unique to all infectious causes of cancer [90]. Nevertheless, HPVs are considered a necessary but not sufficient cause of HPV-associated cancers [4][91][92][93] and a number of co-factors and risk-factors have been documented [94]. These co-factors are represented by (i) coincident infectious agents such as EBV, HSV-2, HIV and Chlamydia [93][95][96][97][98][99]; (ii) environmental factors (various chemical agents, UV light, immune suppression, stress); (iii) behavioral factors (sexual partners, parity and smoking) and (iv) genetic and epigenetic factors (various polymorphisms in HLA molecules, p53 and GST [100][101], the genetic predisposition known as epidermodysplasia verruciformis, and methylation status of the viral genome) (reviewed in [1][102][103]). Several studies have indicated that cervical cancer development and progression may be closely associated with a dual-infection with HPV and EBV [4][97]. Infiltrating EBV-infected lymphocytes have been detected in cervical lesions containing episomal hrHPV [97]. The impact of co-incident chronic inflammation and immune modulation via these infectious co-factors has not been studied mechanistically in preclinical models and warrants further study.

–

HPV of the betapapillomavirus group such as HPV5 and HPV8 are associated with rare incidences of skin cancers, and these and other members of this family are considered to also play a role in non-melanoma skin cancers [104][91][105]. The oncogenic potential of members of the betapapillomaviruses are hypothesized to require co-factors including UV light and p53 polymorphisms [106]. The roles of the viral oncogenes in these instances include activation of telomerase and extension of cell life span via E6 [107], and a potential cancer correlation with E6 and polymorphisms in p53 [85][106].

–

Tissue tropism, latency and viral reservoirs

There is an exquisite interplay between HPV persistence, tissue tropism and the host innate and adaptive immune response. The keratinocyte is the exclusive host cell of HPVs, and has significant potential to mount both anti-viral responses to PV infections as well as activate adaptive immunity. The tissue tropism introduces the concept of micro-environments in which the host keratinocytes and local immune monitoring are not necessarily identical at different anatomical sites. Possible differences in immune monitoring as well as differences in the natural microbiome in oral and anogenital mucosa also provide mechanistic explanations for HPV tissue tropism [26][31]. Epithelial stem cells have attracted interest as a primary source of susceptible cells for initial infection [26][30]. The epithelial transition zone may also act as a stem cell niche and thus represents a key location for cellular transformation by accumulated genetic mutations or viral transformation resulting in tumor formation [30]. Several proteins that are induced during wounding are expressed specifically within transition zones, and/or on epithelial stem cells, and may correlate or contribute to HPV-associated transformation [108][109][110].

–

The exquisite and regional tissue restriction of some HPV types is well-illustrated by such examples as the association of HPV7 with meat-handlers [111]. HPV7 appears to be sufficiently common, but the clinical disease of hand warts appears to be correlated with the unique occupational damage to the hands of these workers rather than via person-to-person transmission of HPV7 [112]. Other skin-tropic HPV types are more common on feet and hands (HPV1/2/4/60/63). Clearly, some HPV types can discriminate at the level of regional tissue sites that the investigator would predict to be tissue-site equivalent. Cellular and molecular differences in keratinocytes are a plausible explanation for these regional specificities, as is the potential differences in the local microbiome and differential immune responsiveness in situ. This phenomenon represents another fruitful area of research for the papillomavirus community. Note too that some HPV types show little tissue restriction and can be found at both mucosal and cutaneous sites (e.g. members of the beta- and gammapapillomaviruses [113]).

–

The concept of viral latency in papillomaviruses has also raised significant interest in the research community [15][114]. Strong circumstantial evidence exists with patients that undergo immunosuppression either by infection (e.g. HIV) or for organ transplantation. Again, the existence of viral DNA and RNA at low levels in clinically normal tissues following immune clearance is confirmed in preclinical models [115]. Additional studies to determine the viral mRNA profile would improve our understanding of HPV latency and help determine whether the viral program is reduced in content via immune (and/or innate immune) monitoring or whether distinct components of the viral life cycle are silenced in keeping with other viruses known to have classical latent phenotypes (such as herpesviruses).

–

The concept of viral reservoirs for secondary infections has attracted limited coverage in the literature [116]. The consensus view is that viral reservoirs include multiple localized infections that may be either clinically active or asymptomatic but which continue to shed infectious virions leading to self-inoculation. Such scenarios may provide a source of virus that can set up secondary infections at transition zones, or sites that are known to progress to malignancies. Recently, non-genital sources of virus present under fingernails has been recorded that could potentially provide an alternate reservoir for future infection although the investigators concluded that this method of transmission is unlikely [117].

–

Codon usage profiles of papillomavirus proteins show striking differences between the papillomavirus groups [70], between viral proteins [118][119] and disease phenotypes [70]. These studies highlight another intriguing mechanism by which papillomavirus tissue tropism could be influenced, and such concepts can be directly assessed using preclinical papillomavirus models and mutational analyses [120].

–

Tropism and tissue site selectivity; lessons learned from a mouse PV (MmuPV-1) model.

A new mouse PV model has recently been described that infects cutaneous [121] and mucosal tissues [122]. Although this virus type is clearly genetically dissimilar to the more well-studied alphapapillomaviruses, the tissue restriction of HPV for human tissues prevents mechanistic study of these viruses in vivo and thus preclinical models provide insights into the tissue selectivity of papillomaviruses. We have observed that when the oral cavities of mice are secondarily exposed to MmuPV-1 infectious virions without experimental wounding, select sites in the oral cavity (circumvallate papilla, base of tongue) become preferentially infected despite the observation that most oral mucosa is susceptible to this virus (Figure 2). These studies mimic to some extent, the pre-selection of oral HPV-associated cancers that are confined to the base of tongue, tonsil and oropharynx [5]. We do not yet understand why certain sites in the oral cavity are more vulnerable to HPV malignancies than other sites. Some new observations regarding stem cells in skin hair follicles, cervix and anal epithelial transition zones and tonsillar crypts are suggestive of such cells being prime targets for HPV infection, and sites that preferentially progress towards malignancy [26][31].

TREATMENT AND CURABILITY

Questions relevant to this section:

- Why do some patients clear their HPV infections and others do not? Are there genetic, epigenetic and/or environmental components to these different outcomes?

- Why do many patients clear infections against some HPV types but not others?

- Do pre-existing co-infections with other infectious agents increase or decrease susceptibility to and persistence of HPV infection?

- Does immune clearance of HPV infections lead to sterilization of the infection or immune monitoring of a subclinical persistent infection?

- Why are there so many treatment failures when clinical “cures” appear to have been achieved with various different strategies?

- Can we develop successful T-cell based immunity to existing HPV disease that can control/clear persistent disease and cancer? Are there additional neo-antigens (in cells with integrated viral DNA) such as host-viral fusion proteins that could serve as potential CD8 T-cell epitopes?

–

Asymptomatic HPV disease remains untreated as a default. Active clinical disease is diagnosed by both sensitive viral DNA detection methods, and histology or cytology. Monitoring programs (e.g. PAP test) are used to determine the timing and severity of intervention. The PAP smear test examines cells collected by lavage from vaginal sites and cells are examined for histological abnormalities, for viral DNA or for other diagnostic indicators such as increased p16INK4a immunostaining, acid phosphatase positivity, p53, p63, various host microRNA and other additional novel markers [64][67][100][103][109][123][124][125][126][127][128][129]. Biopsy material is examined for histological markers and graded using a CIN classification (stages I to IV) or via the Bethesda system for high or low grade dysplasia. Ablative or topical treatments are mostly on an ad hoc basis of treatment of visible lesions seen by colposcopy or acid-white staining.

–

Therapeutic interventions

Three prophylactic vaccines are currently approved for control of several high-risk HPV types, and two low-risk types commonly found in genital warts. These include Gardasil (HPV6, 11, 16 and 18), Cervarix (HPV16, 18) and Gardasil9 (HPV6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 35, 45, 52, 58) [130][131][132]. The vaccines use virus-like particles for the designated HPV types and trigger high titers of type-specific neutralizing antibodies and excellent protection against vaccine-related HPV types [133][134][135]. Some limited cross-protection against vaccine-related types has been observed in clinical trials [136]. Second-generation vaccines have increased the number of HPV types in the vaccine (e.g. Gardasil9) and are now considering L2-based vaccines that are more broadly cross-protective [137][138].

–

Therapeutic vaccines based on T-cell responses to virus-infected tissues have been extensively tested in preclinical models, but have enjoyed much less success in clinical trials. Nevertheless, there have been recent encouraging results using long peptide vaccines from HPV16 E6 and E7 for therapeutic T-cell based regression of vaginal intraepithelial infections [139][140]. Adoptive transfer of HPV16-reactive T-cells also shows promise against cervical cancer in an initial clinical trial [141]. As we go forward with new and improved immunotherapeutic approaches to manage HPV-associated cancers, there are several challenges to our knowledge base that require further studies. Some examples follow:

- We need to better understand the various immune suppressive events that occur in situ in HPV-associated cancers that are highly localized [142].

- We need to design improved strategies to overcome localized T-cell exhaustion and other functional deficiencies that are increasingly being defined in other chronic viral infections [143].

- We need to better understand and then counteract HPV-induced innate and adaptive immune escape mechanisms to improve T-cell recognition and elimination of HPV infected cells.

- We need to improve our understanding of T-cell homing to non-immunological tissues (vaginal, anal and oral mucosal epithelium) in order to improve the frequency and effector functions of CD8 T-cells [144].

- We need to improve therapeutic activation of HPV-specific T-cells and assess other potential non-HPV epitopes arising from mutations in cervical cancer to better design vaccines that develop long-lasting immunity [145][146].

–

Finally, there may be productive opportunities to explore possible sources of neo-antigens in HPV-containing cancer cells that are represented as novel mutations in host cell proteins that provide new CD4 and CD8 epitopes [147][148][149]. Another possible source of neo-antigens may arise in cancer cells with integrated viral genomes that could express hybrid host/viral fusion proteins. Additional sources of neo-antigens may arise from altered expression of viral proteins through the process of defective ribosomal products (DRiPs) [150][151][152].

MOLECULAR MECHANISMS OF INFECTION

Questions relevant to this section:

- Is wounding essential for successful infection of tissues by infectious virions?

- Can HPV infections be established from virions that enter sites of epithelial “conflict” as found in transition zones, hair follicles and tonsillar crypts, without the need for environmental wounding?

- Do all HPV types use the same molecular entry pathway?

- Do different HPV types interact with different host factors during disease persistence and progression?

- Is the mechanism of virion entry different for cutaneous versus mucosal epithelium?

- What are the molecular, genetic and immunological criteria that define tissue-tropism of PVs?

–

Papillomaviruses are predominantly epitheliotropic. Only a small number of PV types confined to the deltapapillomavirus group induce fibropapillomas in which both epithelial and fibroblast cells are infected [10]. Current dogma proposes that virions enter sites of epithelial damage from wounding. Such wounds expose the basal cells and the basement membrane of the epithelium to virions and the subsequent wound-healing environment is believed to be essential for the establishment and maintenance of PV infections. Wounding may be achieved via mechanical, chemical or biological means. Mechanical damage to skin can occur via cuts, abrasions and UV damage; via intercourse for vaginal and anal mucosa and via eating, smoking and oral cleansing for oral mucosa. Chemical damage can occur via contraceptives, suppositives, oral and vaginal lavage solutions and oxidative damaging agents. Biological damage can occur via co-incident microbial agents such as bacteria, protozoans and fungi that can erode tissues and the basement membrane leading to remodeling and repair of the epithelium [25]. Once basal cells are infected, PV genomes proceed through 3 stages of replication that can be summarized as (i) initial amplification within basal keratinocytes,(ii) followed next by a maintenance phase as the infection becomes established, then (iii) a vegetative stage where viral genomes are amplified to high copy and packaged into virions [40].

–

In vitro models of entry

Molecular events of entry have been studied extensively in cell culture systems (reviewed in [153][154][155][156]). Both native virions from natural infections, xenografts and organotypic cultures as well as synthetic particles prepared in 293TT cells [157] have been used for studies on entry kinetics and receptor analyses [158]. A general consensus of these studies describes a key role for heparin-sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) as a primary binding receptor both in vitro [159] and in a pseudovirus infection model of cervicovaginal tissues in mice [23]. Variation in responses is seen when using different viral and pseudoviral systems, different cell lines and different methods for preparing reagents and between different viral types [154].

–

A series of different host proteins are involved in the various early stages of binding and entry. These include surface heparin-sulfate proteoglycans (e.g. syndecans) [160][161], extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins (e.g. Laminin 332) [28], anexin A2 [162], cyclophilins [163] and tetraspanins [164]. Again, a general consensus model supports the hypothesis that virion binding to HSPGs and ECM components leads to structural changes to the capsid surface allowing exposure of a region of the minor capsid protein to furinase cleavage [165] and subsequent transfer to a secondary receptor for receptor-mediated uptake [166]. Various studies have demonstrated both support and contradiction to several of these proposed steps suggesting that there may be different uptake and entry pathways for the different HPV types rather than a unifying single molecular entry pathway [154][167][168].

–

In vivo models of entry

Several animal preclinical models have been used to assess some features of viral entry in situ onto skin and mucosal sites. These studies include mouse cervicovaginal [23] and rabbit skin infection models [169]. These studies provide evidence for a role for HSPGs, for virion targeting to the ECM, and for pre-wounding prior to infection [22][23]. The studies also clearly indicate that the PV capsid proteins do not account for tissue and species tropism at the level of viral entry into the epithelial cells. Thus, HPV capsids can efficiently deliver papillomavirus genomes into rabbit skin [169] and plasmid genomes into mouse skin and mucosa [23].

CONCLUSIONS

Do we have sufficient knowledge about the complex interplay between immune mechanisms of escape, viral carcinogenesis, host innate sensors, transcriptional regulation and codon usage profiles to determine the species and tissue tropism of papillomaviruses?

–

In summing up, the PV research community has built an impressive body of knowledge on the biological, clinical and pathological activities of papillomaviruses. Significant challenges remain in the arena of improved treatments for persistent and latent HPV infections and associated cancers. Preclinical PV models will continue to provide opportunities for more mechanistic studies where the virus and host can be manipulated both genetically and pharmacologically to tease apart contributions of the various components of the virus life cycle. Already, these viruses have enriched our knowledge of viral evolution, tumor suppressor function, host restriction factors, innate immunity, codon usage profiles, viral vaccines, immunotherapy, DNA damage response mechanisms, keratinocyte biology and viral tissue tropism. Future studies will allow us to assess the impact of the current prophylactic vaccines on a select set of HPV types and the selection pressures these vaccines impose on viral evolution. Papillomaviruses have provided a resource for a variety of expertise spanning the fields of virology, immunology, pathology, gynecology, evolutionary biology, vaccine manufacture, carcinogenesis and molecular virology. Questions remaining will continue to challenge future researchers as we continue to study these fascinating viruses.

References

- J. Doorbar, W. Quint, L. Banks, I.G. Bravo, M. Stoler, T.R. Broker, and M.A. Stanley, "The Biology and Life-Cycle of Human Papillomaviruses", Vaccine, vol. 30, pp. F55-F70, 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.06.083

- N. Egawa, K. Egawa, H. Griffin, and J. Doorbar, "Human Papillomaviruses; Epithelial Tropisms, and the Development of Neoplasia", Viruses, vol. 7, pp. 3863-3890, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/v7072802

- H. zur Hausen, "Papillomaviruses in the causation of human cancers — a brief historical account", Virology, vol. 384, pp. 260-265, 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2008.11.046

- D.A. Galloway, and L.A. Laimins, "Human papillomaviruses: shared and distinct pathways for pathogenesis", Current Opinion in Virology, vol. 14, pp. 87-92, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.coviro.2015.09.001

- J. Doorbar, N. Egawa, H. Griffin, C. Kranjec, and I. Murakami, "Human papillomavirus molecular biology and disease association", Reviews in Medical Virology, vol. 25, pp. 2-23, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/rmv.1822

- M.L. Gillison, A.K. Chaturvedi, W.F. Anderson, and C. Fakhry, "Epidemiology of Human Papillomavirus–Positive Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma", Journal of Clinical Oncology, vol. 33, pp. 3235-3242, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2015.61.6995

- L. Alemany, M. Saunier, I. Alvarado-Cabrero, B. Quirós, J. Salmeron, H. Shin, E.C. Pirog, N. Guimerà, G. Hernandez-Suarez, A. Felix, O. Clavero, B. Lloveras, E. Kasamatsu, M.T. Goodman, B.Y. Hernandez, J. Laco, L. Tinoco, D.T. Geraets, C.F. Lynch, V. Mandys, M. Poljak, R. Jach, J. Verge, C. Clavel, C. Ndiaye, J. Klaustermeier, A. Cubilla, X. Castellsagué, I.G. Bravo, M. Pawlita, W.G. Quint, N. Muñoz, F.X. Bosch, S. de Sanjosé, and . , "Human papillomavirus DNA prevalence and type distribution in anal carcinomas worldwide", International Journal of Cancer, vol. 136, pp. 98-107, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ijc.28963

- I.G. Bravo, and M. Félez-Sánchez, "Papillomaviruses", Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health, vol. 2015, pp. 32-51, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/emph/eov003

- K. Van Doorslaer, H. Bernard, Z. Chen, E. de Villiers, H.Z. Hausen, and R.D. Burk, "Papillomaviruses: evolution, Linnaean taxonomy and current nomenclature", Trends in Microbiology, vol. 19, pp. 49-50, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2010.11.004

- . Bioinformatics and Computational Biosciences Branch at the NIAID Offic of Cyber Infrastructure and Computational Biology, "Papillomavirus Episteme.", Available at: https://pave.niaid.nih.gov/. Accessed 15.06.2016, 2016.

- D. Bzhalava, L.S.A. Mühr, C. Lagheden, J. Ekström, O. Forslund, J. Dillner, and E. Hultin, "Deep sequencing extends the diversity of human papillomaviruses in human skin", Scientific Reports, vol. 4, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/srep05807

- N. Muñoz, F.X. Bosch, S. de Sanjosé, R. Herrero, X. Castellsagué, K.V. Shah, P.J. Snijders, and C.J. Meijer, "Epidemiologic Classification of Human Papillomavirus Types Associated with Cervical Cancer", New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 348, pp. 518-527, 2003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa021641

- M. Arbyn, M. Tommasino, C. Depuydt, and J. Dillner, "Are 20 human papillomavirus types causing cervical cancer?", The Journal of Pathology, vol. 234, pp. 431-435, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/path.4424

- F.X. Bosch, T.R. Broker, D. Forman, A. Moscicki, M.L. Gillison, J. Doorbar, P.L. Stern, M. Stanley, M. Arbyn, M. Poljak, J. Cuzick, P.E. Castle, J.T. Schiller, L.E. Markowitz, W.A. Fisher, K. Canfell, L.A. Denny, E.L. Franco, M. Steben, M.A. Kane, M. Schiffman, C.J. Meijer, R. Sankaranarayanan, X. Castellsagué, J.J. Kim, M. Brotons, L. Alemany, G. Albero, M. Diaz, and S.D. Sanjosé, "Comprehensive Control of Human Papillomavirus Infections and Related Diseases", Vaccine, vol. 31, pp. H1-H31, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.10.003

- T.R. Broker, G. Jin, A. Croom-Rivers, S.M. Bragg, M. Richardson, L.T. Chow, S.H. Vermund, R.D. Alvarez, P.G. Pappas, K.E. Squires, and C.J. Hoesley, "Viral latency--the papillomavirus model.", Developments in biologicals, 2001. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11761260

- E. de Villiers, "Cross-roads in the classification of papillomaviruses", Virology, vol. 445, pp. 2-10, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2013.04.023

- M. Van Ranst, J.B. Kaplan, and R.D. Burk, "Phylogenetic Classification of Human Papillomaviruses: Correlation With Clinical Manifestations", Journal of General Virology, vol. 73, pp. 2653-2660, 1992. http://dx.doi.org/10.1099/0022-1317-73-10-2653

- S. Jeckel, E. Loetzsch, E. Huber, F. Stubenrauch, and T. Iftner, "Identification of the E9^E2C cDNA and Functional Characterization of the Gene Product Reveal a New Repressor of Transcription and Replication in Cottontail Rabbit Papillomavirus", Journal of Virology, vol. 77, pp. 8736-8744, 2003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/jvi.77.16.8736-8744.2003

- F. Stubenrauch, M. Hummel, T. Iftner, and L.A. Laimins, "The E8^E2C Protein, a Negative Regulator of Viral Transcription and Replication, Is Required for Extrachromosomal Maintenance of Human Papillomavirus Type 31 in Keratinocytes", Journal of Virology, vol. 74, pp. 1178-1186, 2000. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/jvi.74.3.1178-1186.2000

- D. DiMaio, and L.M. Petti, "The E5 proteins", Virology, vol. 445, pp. 99-114, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2013.05.006

- M. Ajiro, and Z. Zheng, "E6^E7, a Novel Splice Isoform Protein of Human Papillomavirus 16, Stabilizes Viral E6 and E7 Oncoproteins via HSP90 and GRP78", mBio, vol. 6, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/mbio.02068-14

- N.M. Cladel, J. Hu, K. Balogh, A. Mejia, and N.D. Christensen, "Wounding prior to challenge substantially improves infectivity of cottontail rabbit papillomavirus and allows for standardization of infection", Journal of Virological Methods, vol. 148, pp. 34-39, 2008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jviromet.2007.10.005

- J.N. Roberts, C.B. Buck, C.D. Thompson, R. Kines, M. Bernardo, P.L. Choyke, D.R. Lowy, and J.T. Schiller, "Genital transmission of HPV in a mouse model is potentiated by nonoxynol-9 and inhibited by carrageenan", Nature Medicine, vol. 13, pp. 857-861, 2007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nm1598

- J. Doorbar, "The E4 protein; structure, function and patterns of expression", Virology, vol. 445, pp. 80-98, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2013.07.008

- B. Singh, C. Fleury, F. Jalalvand, and K. Riesbeck, "Human pathogens utilize host extracellular matrix proteins laminin and collagen for adhesion and invasion of the host", FEMS Microbiology Reviews, vol. 36, pp. 1122-1180, 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6976.2012.00340.x

- E.J. Yang, M.C. Quick, S. Hanamornroongruang, K. Lai, L.A. Doyle, F.D. McKeon, W. Xian, C.P. Crum, and M. Herfs, "Microanatomy of the cervical and anorectal squamocolumnar junctions: a proposed model for anatomical differences in HPV-related cancer risk", Modern Pathology, vol. 28, pp. 994-1000, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2015.54

- M. Schelhaas, H. Ewers, M. Rajamäki, P.M. Day, J.T. Schiller, and A. Helenius, "Human Papillomavirus Type 16 Entry: Retrograde Cell Surface Transport along Actin-Rich Protrusions", PLoS Pathogens, vol. 4, pp. e1000148, 2008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1000148

- T.D. Culp, L.R. Budgeon, M.P. Marinkovich, G. Meneguzzi, and N.D. Christensen, "Keratinocyte-Secreted Laminin 5 Can Function as a Transient Receptor for Human Papillomaviruses by Binding Virions and Transferring Them to Adjacent Cells", Journal of Virology, vol. 80, pp. 8940-8950, 2006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00724-06

- J.L. Smith, D.S. Lidke, and M.A. Ozbun, "Virus activated filopodia promote human papillomavirus type 31 uptake from the extracellular matrix", Virology, vol. 381, pp. 16-21, 2008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2008.08.040

- A.J. Mcnairn, and G. Guasch, "Epithelial transition zones: merging microenvironments, niches, and cellular transformation.", European journal of dermatology : EJD, 2011. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21628126

- J. Mirkovic, B.E. Howitt, P. Roncarati, S. Demoulin, M. Suarez‐Carmona, P. Hubert, F.D. McKeon, W. Xian, A. Li, P. Delvenne, C.P. Crum, and M. Herfs, "Carcinogenic HPV infection in the cervical squamo‐columnar junction", The Journal of Pathology, vol. 236, pp. 265-271, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/path.4533

- I.H. Frazer, "Interaction of human papillomaviruses with the host immune system: A well evolved relationship", Virology, vol. 384, pp. 410-414, 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2008.10.004

- M.A. Stanley, and J.C. Sterling, "Host Responses to Infection with Human Papillomavirus", Current Problems in Dermatology, pp. 58-74, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000355964

- G.H. Ashrafi, E. Tsirimonaki, B. Marchetti, P.M. O'Brien, G.J. Sibbet, L. Andrew, and M.S. Campo, "Down-regulation of MHC class I by bovine papillomavirus E5 oncoproteins", Oncogene, vol. 21, pp. 248-259, 2002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.onc.1205008

- E. van Esch, B. Tummers, V. Baartmans, E. Osse, N. ter Haar, M. Trietsch, B. Hellebrekers, C. Holleboom, H. Nagel, L. Tan, G. Fleuren, M. van Poelgeest, S. van der Burg, and E. Jordanova, "Alterations in classical and nonclassical HLA expression in recurrent and progressive HPV‐induced usual vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia and implications for immunotherapy", International Journal of Cancer, vol. 135, pp. 830-842, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ijc.28713

- S. Um, J. Rhyu, E. Kim, K. Jeon, E. Hwang, and J. Park, "Abrogation of IRF-1 response by high-risk HPV E7 protein in vivo", Cancer Letters, vol. 179, pp. 205-212, 2002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0304-3835(01)00871-0

- P. Barnard, and N.A. McMillan, "The Human Papillomavirus E7 Oncoprotein Abrogates Signaling Mediated by Interferon-α", Virology, vol. 259, pp. 305-313, 1999. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/viro.1999.9771

- M. Beglin, M. Melar-New, and L. Laimins, "Human Papillomaviruses and the Interferon Response", Journal of Interferon & Cytokine Research, vol. 29, pp. 629-635, 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/jir.2009.0075

- S. Hong, and L.A. Laimins, "Regulation of the Life Cycle of HPVs by Differentiation and the DNA Damage Response", Future Microbiology, vol. 8, pp. 1547-1557, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.2217/fmb.13.127

- C. McKinney, K. Hussmann, and A. McBride, "The Role of the DNA Damage Response throughout the Papillomavirus Life Cycle", Viruses, vol. 7, pp. 2450-2469, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/v7052450

- N.A. Wallace, and D.A. Galloway, "Manipulation of cellular DNA damage repair machinery facilitates propagation of human papillomaviruses", Seminars in Cancer Biology, vol. 26, pp. 30-42, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.semcancer.2013.12.003

- E.M. van Esch, M.I. van Poelgeest, J.B.M. Trimbos, G.J. Fleuren, E.S. Jordanova, and S.H. van der Burg, "Intraepithelial macrophage infiltration is related to a high number of regulatory T cells and promotes a progressive course of HPV‐induced vulvar neoplasia", International Journal of Cancer, vol. 136, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ijc.29173

- S.J.A.M. Santegoets, E.M. Dijkgraaf, A. Battaglia, P. Beckhove, C.M. Britten, A. Gallimore, A. Godkin, C. Gouttefangeas, T.D. de Gruijl, H.J.P.M. Koenen, A. Scheffold, E.M. Shevach, J. Staats, K. Taskén, T.L. Whiteside, J.R. Kroep, M.J.P. Welters, and S.H. van der Burg, "Monitoring regulatory T cells in clinical samples: consensus on an essential marker set and gating strategy for regulatory T cell analysis by flow cytometry", Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy, vol. 64, pp. 1271-1286, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00262-015-1729-x

- A. Handisurya, P.M. Day, C.D. Thompson, M. Bonelli, D.R. Lowy, and J.T. Schiller, "Strain-Specific Properties and T Cells Regulate the Susceptibility to Papilloma Induction by Mus musculus Papillomavirus 1", PLoS Pathogens, vol. 10, pp. e1004314, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1004314

- N. Reusser, C. Downing, J. Guidry, and S. Tyring, "HPV Carcinomas in Immunocompromised Patients", Journal of Clinical Medicine, vol. 4, pp. 260-281, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/jcm4020260

- U. Wieland, A. Kreuter, and H. Pfister, "Human Papillomavirus and Immunosuppression", Current Problems in Dermatology, pp. 154-165, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000357907

- V. Shamanin, H.Z. Hausen, D. Lavergne, C.M. Proby, I.M. Leigh, C. Neumann, H. Hamm, M. Goos, U. Haustein, E.G. Jung, G. Plewig, H. Wolff, and E. de Villiers, "Human Papillomavirus Infections in Nonmelanoma Skin Cancers From Renal Transplant Recipients and Nonimmunosuppressed Patients", JNCI Journal of the National Cancer Institute, vol. 88, pp. 802-811, 1996. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jnci/88.12.802

- J. Salmon, M. Nonnenmacher, S. Cazé, P. Flamant, O. Croissant, G. Orth, and F. Breitburd, "Variation in the Nucleotide Sequence of Cottontail Rabbit Papillomavirus a and b Subtypes Affects Wart Regression and Malignant Transformation and Level of Viral Replication in Domestic Rabbits", Journal of Virology, vol. 74, pp. 10766-10777, 2000. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/jvi.74.22.10766-10777.2000

- J. Hu, N.M. Cladel, M.D. Pickel, and N.D. Christensen, "Amino Acid Residues in the Carboxy-Terminal Region of Cottontail Rabbit Papillomavirus E6 Influence Spontaneous Regression of Cutaneous Papillomas", Journal of Virology, vol. 76, pp. 11801-11808, 2002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/jvi.76.23.11801-11808.2002

- J. Hu, X. Peng, N.M. Cladel, M.D. Pickel, and N.D. Christensen, "Large cutaneous rabbit papillomas that persist during cyclosporin A treatment can regress spontaneously after cessation of immunosuppression", Journal of General Virology, vol. 86, pp. 55-63, 2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1099/vir.0.80448-0

- M. Reinholz, Y. Kawakami, S. Salzer, A. Kreuter, Y. Dombrowski, S. Koglin, S. Kresse, T. Ruzicka, and J. Schauber, "HPV16 activates the AIM2 inflammasome in keratinocytes", Archives of Dermatological Research, vol. 305, pp. 723-732, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00403-013-1375-0

- C.J. Warren, T. Xu, K. Guo, L.M. Griffin, J.A. Westrich, D. Lee, P.F. Lambert, M.L. Santiago, and D. Pyeon, "APOBEC3A Functions as a Restriction Factor of Human Papillomavirus", Journal of Virology, vol. 89, pp. 688-702, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.02383-14

- J. Vartanian, D. Guétard, M. Henry, and S. Wain-Hobson, "Evidence for Editing of Human Papillomavirus DNA by APOBEC3 in Benign and Precancerous Lesions", Science, vol. 320, pp. 230-233, 2008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1153201

- C. Habiger, G. Jäger, M. Walter, T. Iftner, and F. Stubenrauch, "Interferon Kappa Inhibits Human Papillomavirus 31 Transcription by Inducing Sp100 Proteins", Journal of Virology, vol. 90, pp. 694-704, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.02137-15

- J. Reiser, J. Hurst, M. Voges, P. Krauss, P. Münch, T. Iftner, and F. Stubenrauch, "High-Risk Human Papillomaviruses Repress Constitutive Kappa Interferon Transcription via E6 To Prevent Pathogen Recognition Receptor and Antiviral-Gene Expression", Journal of Virology, vol. 85, pp. 11372-11380, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.05279-11

- I. Lo Cigno, M. De Andrea, C. Borgogna, S. Albertini, M.M. Landini, A. Peretti, K.E. Johnson, B. Chandran, S. Landolfo, and M. Gariglio, "The Nuclear DNA Sensor IFI16 Acts as a Restriction Factor for Human Papillomavirus Replication through Epigenetic Modifications of the Viral Promoters", Journal of Virology, vol. 89, pp. 7506-7520, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00013-15

- U.A. Hasan, E. Bates, F. Takeshita, A. Biliato, R. Accardi, V. Bouvard, M. Mansour, I. Vincent, L. Gissmann, T. Iftner, M. Sideri, F. Stubenrauch, and M. Tommasino, "TLR9 Expression and Function Is Abolished by the Cervical Cancer-Associated Human Papillomavirus Type 16", The Journal of Immunology, vol. 178, pp. 3186-3197, 2007. http://dx.doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.3186

- Y. Hao, J. Yuan, A. Abudula, A. Hasimu, N. Kadeer, and X. Guo, "TLR9 expression in uterine cervical lesions of Uyghur women correlate with cervical cancer progression and selective silencing of human papillomavirus 16 E6 and E7 oncoproteins in vitro.", Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention : APJCP, 2014. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25081715

- M. Niebler, X. Qian, D. Höfler, V. Kogosov, J. Kaewprag, A.M. Kaufmann, R. Ly, G. Böhmer, R. Zawatzky, F. Rösl, and B. Rincon-Orozco, "Post-Translational Control of IL-1β via the Human Papillomavirus Type 16 E6 Oncoprotein: A Novel Mechanism of Innate Immune Escape Mediated by the E3-Ubiquitin Ligase E6-AP and p53", PLoS Pathogens, vol. 9, pp. e1003536, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1003536

- R. Karim, B. Tummers, C. Meyers, J.L. Biryukov, S. Alam, C. Backendorf, V. Jha, R. Offringa, G.B. van Ommen, C.J.M. Melief, D. Guardavaccaro, J.M. Boer, and S.H. van der Burg, "Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Upregulates the Cellular Deubiquitinase UCHL1 to Suppress the Keratinocyte's Innate Immune Response", PLoS Pathogens, vol. 9, pp. e1003384, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1003384

- K. Chow, "Human papillomavirus infection and expression of ATPase family AAA domain containing 3A, a novel anti-autophagy factor, in uterine cervical cancer", International Journal of Molecular Medicine, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.3892/ijmm.2011.743

- L.M. Griffin, L. Cicchini, and D. Pyeon, "Human papillomavirus infection is inhibited by host autophagy in primary human keratinocytes", Virology, vol. 437, pp. 12-19, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2012.12.004

- Z. Surviladze, R.T. Sterk, S.A. DeHaro, and M.A. Ozbun, "Cellular Entry of Human Papillomavirus Type 16 Involves Activation of the Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase/Akt/mTOR Pathway and Inhibition of Autophagy", Journal of Virology, vol. 87, pp. 2508-2517, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.02319-12

- I. Martinez, A.S. Gardiner, K.F. Board, F.A. Monzon, R.P. Edwards, and S.A. Khan, "Human papillomavirus type 16 reduces the expression of microRNA-218 in cervical carcinoma cells", Oncogene, vol. 27, pp. 2575-2582, 2007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.onc.1210919

- X. Wang, S. Tang, S. Le, R. Lu, J.S. Rader, C. Meyers, and Z. Zheng, "Aberrant Expression of Oncogenic and Tumor-Suppressive MicroRNAs in Cervical Cancer Is Required for Cancer Cell Growth", PLoS ONE, vol. 3, pp. e2557, 2008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0002557

- Z. Zheng, and X. Wang, "Regulation of cellular miRNA expression by human papillomaviruses", Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Gene Regulatory Mechanisms, vol. 1809, pp. 668-677, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbagrm.2011.05.005

- X. Wang, H. Wang, Y. Li, M. Hafner, N.S. Banerjee, S. Tang, D. Briskin, C. Meyers, L.T. Chow, X. Xie, T. Tuschl, and Z. Zheng, "microRNAs are biomarkers of oncogenic human papillomavirus infections", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 111, pp. 4262-4267, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1401430111

- S.H. van der Burg, and C.J. Melief, "Therapeutic vaccination against human papilloma virus induced malignancies", Current Opinion in Immunology, vol. 23, pp. 252-257, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.coi.2010.12.010

- B. Tummers, R. Goedemans, L.P.L. Pelascini, E.S. Jordanova, E.M.G. van Esch, C. Meyers, C.J.M. Melief, J.M. Boer, and S.H. van der Burg, "The interferon-related developmental regulator 1 is used by human papillomavirus to suppress NFκB activation", Nature Communications, vol. 6, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7537

- M. Félez-Sánchez, J. Trösemeier, S. Bedhomme, M.I. González-Bravo, C. Kamp, and I.G. Bravo, "Cancer, Warts, or Asymptomatic Infections: Clinical Presentation Matches Codon Usage Preferences in Human Papillomaviruses", Genome Biology and Evolution, vol. 7, pp. 2117-2135, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/gbe/evv129

- S.S. Liyanage, E. Segelov, S.M. Garland, S.N. Tabrizi, H. Seale, P.J. Crowe, D.E. Dwyer, A. Barbour, A.T. Newall, A. Malik, and C.R. Macintyre, "Role of human papillomaviruses in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma", Asia-Pacific Journal of Clinical Oncology, vol. 9, pp. 12-28, 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-7563.2012.01555.x

- E. Husain, D.M. Prowse, E. Ktori, T. Shaikh, M. Yaqoob, I. Junaid, and S. Baithun, "Human papillomavirus is detected in transitional cell carcinoma arising in renal transplant recipients", Pathology, vol. 41, pp. 245-247, 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00313020902756303

- N. Li, L. Yang, Y. Zhang, P. Zhao, T. Zheng, and M. Dai, "Human Papillomavirus Infection and Bladder Cancer Risk: A Meta-analysis", The Journal of Infectious Diseases, vol. 204, pp. 217-223, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jir248

- M. Cullen, J.F. Boland, M. Schiffman, X. Zhang, N. Wentzensen, Q. Yang, Z. Chen, K. Yu, J. Mitchell, D. Roberson, S. Bass, L. Burdette, M. Machado, S. Ravichandran, B. Luke, M.J. Machiela, M. Andersen, M. Osentoski, M. Laptewicz, S. Wacholder, A. Feldman, T. Raine-Bennett, T. Lorey, P.E. Castle, M. Yeager, R.D. Burk, and L. Mirabello, "Deep sequencing of HPV16 genomes: A new high-throughput tool for exploring the carcinogenicity and natural history of HPV16 infection", Papillomavirus Research, vol. 1, pp. 3-11, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pvr.2015.05.004

- K. Münger, and W.C. Phelps, "The human papillomavirus E7 protein as a transforming and transactivating factor", Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer, vol. 1155, pp. 111-123, 1993. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0304-419x(93)90025-8

- M. Tommasino, and L. Crawford, "Human Papillomavirus E6 and E7: Proteins which deregulate the cell cycle", BioEssays, vol. 17, pp. 509-518, 1995. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/bies.950170607

- J.M. Huibregtse, and S.L. Beaudenon, "Mechanism of HPV E6 proteins in cellular transformation", Seminars in Cancer Biology, vol. 7, pp. 317-326, 1996. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/scbi.1996.0041

- M.M. Pater, G.A. Hughes, D.E. Hyslop, H. Nakshatri, and A. Pater, "Glucocorticoid-dependent oncogenic transformation by type 16 but not type 11 human papilloma virus DNA", Nature, vol. 335, pp. 832-835, 1988. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/335832a0

- F. Thierry, "Transcriptional regulation of the papillomavirus oncogenes by cellular and viral transcription factors in cervical carcinoma", Virology, vol. 384, pp. 375-379, 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2008.11.014

- M.K. Thomas, H.C. Pitot, A. Liem, and P.F. Lambert, "Dominant role of HPV16 E7 in anal carcinogenesis", Virology, vol. 421, pp. 114-118, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2011.09.018

- M. Hufbauer, D. Lazić, M. Reinartz, B. Akgül, H. Pfister, and S.J. Weissenborn, "Skin tumor formation in human papillomavirus 8 transgenic mice is associated with a deregulation of oncogenic miRNAs and their tumor suppressive targets", Journal of Dermatological Science, vol. 64, pp. 7-15, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jdermsci.2011.06.008

- I.H. Frazer, D.M. Leippe, L.A. Dunn, A. Liem, R.W. Tindle, G.J. Fernando, W.C. Phelps, and P.F. Lambert, "Immunological responses in human papillomavirus 16 E6/E7-transgenic mice to E7 protein correlate with the presence of skin disease.", Cancer research, 1995. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7540107

- G. Kondoh, Q. Li, J. Pan, and A. Hakura, "Transgenic models for papillomavirus-associated multistep carcinogenesis.", Intervirology, 1995. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8682614

- M.E. McLaughlin-Drubin, and K. Münger, "Oncogenic activities of human papillomaviruses", Virus Research, vol. 143, pp. 195-208, 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.virusres.2009.06.008

- J. Fei, and E. de Villiers, "Differential Regulation of Cutaneous Oncoprotein HPVE6 by wtp53, Mutant p53R248W and ΔNp63α is HPV Type Dependent", PLoS ONE, vol. 7, pp. e35540, 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0035540

- S. Pandey, and . Chandravati, "Autophagy in cervical cancer: an emerging therapeutic target.", Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention : APJCP, 2012. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23244072

- C. Borgogna, M. Landini, S. Lanfredini, J. Doorbar, J. Bouwes Bavinck, K. Quint, M. de Koning, R. Genders, and M. Gariglio, "Characterization of skin lesions induced by skin-tropic α- and β-papillomaviruses in a patient with epidermodysplasia verruciformis", British Journal of Dermatology, vol. 171, pp. 1550-1554, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bjd.13156

- R. van Baars, H. Griffin, Z. Wu, Y.J. Soneji, M.M. van de Sandt, R. Arora, J. van der Marel, B. ter Harmsel, R. Jach, K. Okon, H. Huras, D. Jenkins, W.G. Quint, and J. Doorbar, "Investigating Diagnostic Problems of CIN1 and CIN2 Associated With High-risk HPV by Combining the Novel Molecular Biomarker PanHPVE4 With P16INK4a", American Journal of Surgical Pathology, vol. 39, pp. 1518-1528, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0000000000000498

- H. Griffin, Y. Soneji, R. Van Baars, R. Arora, D. Jenkins, M. van de Sandt, Z. Wu, W. Quint, R. Jach, K. Okon, H. Huras, A. Singer, and J. Doorbar, "Stratification of HPV-induced cervical pathology using the virally encoded molecular marker E4 in combination with p16 or MCM", Modern Pathology, vol. 28, pp. 977-993, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2015.52

- H. zur Hausen, and E. de Villiers, "Reprint of: Cancer “Causation” by Infections—Individual Contributions and Synergistic Networks", Seminars in Oncology, vol. 42, pp. 207-222, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/j.seminoncol.2015.02.019

- F.X. Bosch, and S. de Sanjosé, "The epidemiology of human papillomavirus infection and cervical cancer.", Disease markers, 2007. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17627057

- S. Cavalcanti, L. Zardo, M. Passos, and L. Oliveira, "Epidemiological Aspects of Human Papillomavirus Infection and Cervical Cancer in Brazil", Journal of Infection, vol. 40, pp. 80-87, 2000. http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/jinf.1999.0596

- S. Bellaminutti, S. Seraceni, F. De Seta, T. Gheit, M. Tommasino, and M. Comar, "HPV and Chlamydia trachomatis co‐detection in young asymptomatic women from high incidence area for cervical cancer", Journal of Medical Virology, vol. 86, pp. 1920-1925, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jmv.24041

- A. Hildesheim, R. Herrero, P.E. Castle, S. Wacholder, M.C. Bratti, M.E. Sherman, A.T. Lorincz, R.D. Burk, J. Morales, A.C. Rodriguez, K. Helgesen, M. Alfaro, M. Hutchinson, I. Balmaceda, M. Greenberg, and M. Schiffman, "HPV co-factors related to the development of cervical cancer: results from a population-based study in Costa Rica", British Journal of Cancer, vol. 84, pp. 1219-1226, 2001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1054/bjoc.2001.1779

- R.J. Landers, J.J. O'Leary, M. Crowley, I. Healy, P. Annis, L. Burke, D. O'Brien, J. Hogan, W.F. Kealy, and F.A. Lewis, "Epstein-Barr virus in normal, pre-malignant, and malignant lesions of the uterine cervix.", Journal of clinical pathology, 1993. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8227411

- J. Marinho‐Dias, J. Ribeiro, P. Monteiro, J. Loureiro, I. Baldaque, R. Medeiros, and H. Sousa, "Characterization of cytomegalovirus and epstein‐barr virus infection in cervical lesions in Portugal", Journal of Medical Virology, vol. 85, pp. 1409-1413, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jmv.23596

- S. Aromseree, C. Pientong, P. Swangphon, A. Chaiwongkot, N. Patarapadungkit, P. Kleebkaow, T. Tungsiriwattana, B. Kongyingyoes, T. Vendrig, J.M. Middeldorp, and T. Ekalaksananan, "Possible contributing role of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) as a cofactor in human papillomavirus (HPV)-associated cervical carcinogenesis", Journal of Clinical Virology, vol. 73, pp. 70-76, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2015.10.015

- J.K. McDougall, J.A. Nelson, D. Myerson, A.M. Beckmann, and D.A. Galloway, "HSV, CMV, and HPV in human neoplasia.", The Journal of investigative dermatology, 1984. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6330227

- S.S. Prakash, W.C. Reeves, G.R. Sisson, M. Brenes, J. Godoy, S. Bacchetti, R.C. de Britton, and W.E. Rawls, "Herpes simplex virus type 2 and human papillomavirus type 16 in cervicitis, dysplasia and invasive cervical carcinoma.", International journal of cancer, 1985. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2981783

- T. Wang, B. Chen, Y. Yang, H. Chen, Y. Wang, A. Cviko, B.J. Quade, D. Sun, A. Yang, F.D. McKeon, and C.P. Crum, "Histologic and immunophenotypic classification of cervical carcinomas by expression of the p53 homologue p63: A study of 250 cases", Human Pathology, vol. 32, pp. 479-486, 2001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/hupa.2001.24324

- S. Palma, F. Novelli, L. Padua, A. Venuti, G. Prignano, L. Mariani, R. Cozzi, D. Tirindelli, and A. Testa, "Interaction between glutathione-S-transferase polymorphisms, smoking habit, and HPV infection in cervical cancer risk", Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology, vol. 136, pp. 1101-1109, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00432-009-0757-3

- E.A. White, and P.M. Howley, "Proteomic approaches to the study of papillomavirus–host interactions", Virology, vol. 435, pp. 57-69, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2012.09.046

- Z. Zheng, "Papillomavirus genome structure, expression, and post-transcriptional regulation", Frontiers in Bioscience, vol. 11, pp. 2286, 2006. http://dx.doi.org/10.2741/1971

- N.A. Wallace, K. Robinson, H.L. Howie, and D.A. Galloway, "β-HPV 5 and 8 E6 Disrupt Homology Dependent Double Strand Break Repair by Attenuating BRCA1 and BRCA2 Expression and Foci Formation", PLOS Pathogens, vol. 11, pp. e1004687, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1004687

- M.C. Feltkamp, M.N. de Koning, J.N.B. Bavinck, and J. ter Schegget, "Betapapillomaviruses: Innocent bystanders or causes of skin cancer", Journal of Clinical Virology, vol. 43, pp. 353-360, 2008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2008.09.009

- K.R. Loeb, M.M. Asgari, S.E. Hawes, Q. Feng, J.E. Stern, M. Jiang, Z.B. Argenyi, E. de Villiers, and N.B. Kiviat, "Analysis of Tp53 Codon 72 Polymorphisms, Tp53 Mutations, and HPV Infection in Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinomas", PLoS ONE, vol. 7, pp. e34422, 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0034422

- K.M. Bedard, M.P. Underbrink, H.L. Howie, and D.A. Galloway, "The E6 Oncoproteins from Human Betapapillomaviruses Differentially Activate Telomerase through an E6AP-Dependent Mechanism and Prolong the Lifespan of Primary Keratinocytes", Journal of Virology, vol. 82, pp. 3894-3902, 2008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01818-07

- V. da Silva-Diz, S. Solé-Sánchez, A. Valdés-Gutiérrez, M. Urpí, D. Riba-Artés, R.M. Penin, G. Pascual, E. González-Suárez, O. Casanovas, F. Viñals, J.M. Paramio, E. Batlle, and P. Muñoz, "Progeny of Lgr5-expressing hair follicle stem cell contributes to papillomavirus-induced tumor development in epidermis", Oncogene, vol. 32, pp. 3732-3743, 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/onc.2012.375

- J.E. Martens, J. Arends, P.J.Q. Van der Linden, B.A.G. De Boer, and T.J.M. Helmerhorst, "Cytokeratin 17 and p63 are markers of the HPV target cell, the cervical stem cell.", Anticancer research, 2004. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15161025

- Q. Chen, H. Cao, and P. Zheng, "LGR5 promotes the proliferation and tumor formation of cervical cancer cells through the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway", Oncotarget, vol. 5, pp. 9092-9105, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.2377

- M. Keefe, A. al-Ghamdi, D. Coggon, N.J. Maitland, P. Egger, C.J. Keefe, A. Carey, and C.M. Sanders, "Cutaneous warts in butchers.", The British journal of dermatology, 1994. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8305325

- M. Keefe, A. al-Ghamdi, D. Coggon, N.J. Maitland, P. Egger, C.J. Keefe, A. Carey, and C.M. Sanders, "Butchers' warts: no evidence for person to person transmission of HPV7.", The British journal of dermatology, 1994. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8305311

- D. Bottalico, Z. Chen, A. Dunne, J. Ostoloza, S. McKinney, C. Sun, N.F. Schlecht, M. Fatahzadeh, R. Herrero, M. Schiffman, and R.D. Burk, "The Oral Cavity Contains Abundant Known and Novel Human Papillomaviruses From the Betapapillomavirus and Gammapapillomavirus Genera", The Journal of Infectious Diseases, vol. 204, pp. 787-792, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jir383

- G.A. Maglennon, "The Biology of Papillomavirus Latency", The Open Virology Journal, vol. 6, pp. 190-197, 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.2174/1874357901206010190

- G.A. Maglennon, P. McIntosh, and J. Doorbar, "Persistence of viral DNA in the epithelial basal layer suggests a model for papillomavirus latency following immune regression", Virology, vol. 414, pp. 153-163, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2011.03.019

- G. Koliopoulos, O. Valari, P. Karakitsos, and E. Paraskevaidis, "Predictors and Clinical Implications of HPV Reservoire Districts for Genital Tract Disease", Current Pharmaceutical Design, vol. 19, pp. 1395-1400, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.2174/1381612811319080005

- T.(. Fu, J.P. Hughes, Q. Feng, A. Hulbert, S.E. Hawes, L.F. Xi, S.M. Schwartz, J.E. Stern, L.A. Koutsky, and R.L. Winer, "Epidemiology of Human Papillomavirus Detected in the Oral Cavity and Fingernails of Mid-Adult Women", Sexually Transmitted Diseases, vol. 42, pp. 677-685, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000362

- K. Zhao, W. Gu, N.X. Fang, N.A. Saunders, and I.H. Frazer, "Gene Codon Composition Determines Differentiation-Dependent Expression of a Viral Capsid Gene in Keratinocytes In Vitro and InVivo", Molecular and Cellular Biology, vol. 25, pp. 8643-8655, 2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.25.19.8643-8655.2005

- N.M. Cladel, A. Bertotto, and N.D. Christensen, "Human alpha and beta papillomaviruses use different synonymous codon profiles", Virus Genes, vol. 40, pp. 329-340, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11262-010-0451-1

- N.M. Cladel, L.R. Budgeon, J. Hu, K.K. Balogh, and N.D. Christensen, "Synonymous codon changes in the oncogenes of the cottontail rabbit papillomavirus lead to increased oncogenicity and immunogenicity of the virus", Virology, vol. 438, pp. 70-83, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2013.01.005

- A. Ingle, S. Ghim, J. Joh, I. Chepkoech, A. Bennett Jenson, and J.P. Sundberg, "Novel Laboratory Mouse Papillomavirus (MusPV) Infection", Veterinary Pathology, vol. 48, pp. 500-505, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0300985810377186

- N.M. Cladel, L.R. Budgeon, K.K. Balogh, T.K. Cooper, J. Hu, and N.D. Christensen, "Mouse papillomavirus MmuPV1 infects oral mucosa and preferentially targets the base of the tongue", Virology, vol. 488, pp. 73-80, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2015.10.030

- K. Selvi, B.A. Badhe, D. Papa, and R. Nachiappa Ganesh, "Role of p16, CK17, p63, and Human Papillomavirus in Diagnosis of Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia and Distinction From Its Mimics", International Journal of Surgical Pathology, vol. 22, pp. 221-230, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1066896913496147

- �.P. Pinto, M. Degen, L.L. Villa, and E.S. Cibas, "Immunomarkers in Gynecologic Cytology: The Search for the Ideal ‘Biomolecular Papanicolaou Test’", Acta Cytologica, vol. 56, pp. 109-121, 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000335065

- K. Srivastava, A. Pickard, S. McDade, and D.J. McCance, "p63 drives invasion in keratinocytes expressing HPV16 E6/E7 genes through regulation of Src-FAK signalling", Oncotarget, vol. 8, pp. 16202-16219, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.3892

- S.S. Wang, M. Trunk, M. Schiffman, R. Herrero, M.E. Sherman, R.D. Burk, A. Hildesheim, M.C. Bratti, T. Wright, A.C. Rodriguez, S. Chen, A. Reichert, C. von Knebel Doeberitz, R. Ridder, and M. von Knebel Doeberitz, "Validation of p16INK4a as a marker of oncogenic human papillomavirus infection in cervical biopsies from a population-based cohort in Costa Rica.", Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology, 2004. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15298958

- J. Zhang, L. Wang, M. Qiu, Z. Liu, W. Qian, Y. Yang, S. Wu, and Y. Feng, "The Protein Levels of MCM7 and p63 in Evaluating Lesion Severity of Cervical Disease", International Journal of Gynecological Cancer, vol. 23, pp. 318-324, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/IGC.0b013e31827f6f06

- G.D. Zielinski, P.J. Snijders, L. Rozendaal, N.F. Daalmeijer, E.K. Risse, F.J. Voorhorst, N.M. Jiwa, H.C. van der Linden, F.A. de Schipper, A.P. Runsink, and C.J. Meijer, "The presence of high‐risk HPV combined with specific p53 and p16INK4a expression patterns points to high‐risk HPV as the main causative agent for adenocarcinoma in situ and adenocarcinoma of the cervix", The Journal of Pathology, vol. 201, pp. 535-543, 2003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/path.1480

- C.M. Martin, K. Astbury, L. Kehoe, J.B. O’Crowley, S. O’Toole, and J.J. O’Leary, "The Use of MYBL2 as a Novel Candidate Biomarker of Cervical Cancer", Methods in Molecular Biology, pp. 241-251, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-2013-6_18