Research Reports:

Microbial Cell, Vol. 3, No. 7, pp. 285 - 292; doi: 10.15698/mic2016.07.512

Filamentation protects Candida albicans from amphotericin B-induced programmed cell death via a mechanism involving the yeast metacaspase, MCA1

Department of Biology, Providence College, 1 Cunningham Square, Providence, Rhode Island 02918, U.S.A..

# These two authors contributed equally to this work.

Keywords: Candida albicans, amphotericin B, caspofungin, MCA1, programmed cell death, filamentation.

Abbreviations:

AMB – amphotericin B,

CAS – caspofungin,

FBS – fetal bovine serum,

GlcNAc – N-acetylglucosamine,

ROS – reactive oxygen species.

Received originally: 06/05/2015 Received in revised form: 25/01/2016

Accepted: 18/03/2016

Published: 25/04/2016

Correspondence:

Rev. Nicanor Pier Giorgio Austriaco, O.P., Ph.D, Department of Biology, Providence College, Providence, RI 02918, U.S.A; Tel: 401-865-1823; Fax: 401-865-2959 naustria@providence.edu

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: David J. Laprade, Melissa S. Brown, Morgan L. McCarthy, James J. Ritch, and Nicanor Austriaco (2016). Filamentation protects Candida albicans from amphotericin B-induced programmed cell death via a mechanism involving the yeast metacaspase, MCA1. Microbial Cell 3(7): 285-292.

Abstract

The budding yeast Candida albicans is one of the most significant fungal pathogens worldwide. It proliferates in two distinct cell types: blastopores and filaments. Only cells that are able to transform from one cell type into the other are virulent in mouse disease models. Programmed cell death is a controlled form of cell suicide that occurs when C. albicans cells are exposed to fungicidal drugs like amphotericin B and caspofungin, and to other stressful conditions. We now provide evidence that suggests that programmed cell death is cell-type specific in yeast: Filamentous C. albicans cells are more resistant to amphotericin B- and caspofungin-induced programmed cell death than their blastospore counterparts. Finally, our genetic data suggests that this phenomenon is mediated by a protective mechanism involving the yeast metacaspase, MCA1.

INTRODUCTION

The budding yeast Candida albicans has emerged as one of the most significant fungal pathogens globally [1]. As an opportunistic pathogen capable of life-threatening systemic infections, C. albicans poses a serious threat to immuno-compromised individuals, including AIDS patients, cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy, organ transplant recipients, and patients with advanced diabetes [2][3][4]. Worldwide, invasive candidiasis is currently regarded as the fourth most common cause of nosocomial infections with an estimated mortality rate of 35% [5][6]. Significantly, resistance to therapies traditionally used to treat candidiasis such as triazoles and amphotericin B is rising [7][8]. Thus, there is a pressing need to develop more effective anti-fungal treatments.

–

There are a number of physiological characteristics of C. albicans known to contribute to its virulence. Most notably, the organism’s ability to undergo a reversible morphological transition from round, budding cells called ‘blastospores,’ to elongated cells attached end-to-end, called ‘filaments,’ is linked to its ability to infect a host: cells unable to become filamentous or vice versa have been shown to be avirulent in mouse and C. elegans models [9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18]. The process by which C. albicans undergoes the transition from blastospores to filaments is known as ‘filamentation’. Within the filamentous form, we further individuate two distinct cellular morphologies. Pseudo-hyphal cells are attached end-to-end, exhibit constrictions at the septa, and have an elongated cell wall, while true hyphal cells of C. albicans are distinguished by the emergence of small cellular protrusions called ‘germ tubes’. While a recent study has shown that virulence can be decoupled from cell type in C. albicans, the connection between cell type and pathogenicity remains an important one [19].

–

Interestingly, there is growing evidence to support the claim that the drugs commonly used to treat patients suf-fering from C. albicans infections, induce cell death [20][21]. Specifically, C. albicans cells cultured in media containing the common anti-fungal drugs, amphotericin B (AMB) and caspofungin (CAS), undergo an apoptotic-like programmed cell death [22][23][24][25]. Programmed cell death is a cell suicide program that is essential for homeostasis, development, and disease prevention in many multi-cellular organisms [26][27][28][29]. When it occurs in yeast, programmed cell death is accompanied by the nicking of DNA, the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and the intracellular activation of the fungal caspases [30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37].

–

In multicellular organisms, the response to programmed cell death is cell-type specific, and the rate of cell death varies widely from tissue to tissue and cell-type to cell-type within the plant or animal [26]. In this paper, we provide evidence that suggests that programmed cell death is also cell-type specific in yeast: filamentous Candida cells are more resistant to amphotericin B- and caspofungin-induced programmed cell death than their blastospore counterparts. Finally, our genetic data suggests that this phenomenon is mediated by a mechanism involving the yeast metacaspase MCA1.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

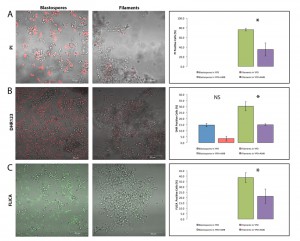

In recent years, it has become evident that programmed cell death occurs in unicellular organisms. For example, in the pathogenic fungus Candida albicans exposure to acetic acid, hydrogen peroxide, AMB, CAS, and farnesol leads to cell death accompanied by hallmark features of mammalian programmed cell death [22] [23][24][36][38]. In multicellular organisms, the response to programmed cell death is cell-type specific, and the rate of cell death varies widely from tissue to tissue and cell type to cell type within the plant or animal [26]. To determine whether or not different forms of yeast respond differently to stimuli that induce programmed cell death, we first investigated whether or not filamentous cells manifest the markers of programmed cell death when they are cultured in media containing AMB. In this study, the clinical isolate SC5314—the parent of strains widely used for molecular analysis—was used as the wild type strain [39]. Briefly, overnight cultures of wild type cells in YPD were resuspended in YPD or YPD containing 10% fetal bovine serum (YPD+FBS) to obtain either blastospores or hyphal cells respectively (Supplemental Figure 1) [10][11][12]. These cells were then resuspended in YPD containing 8 µg/ml AMB for 3 hours. Dihydrorhodamine 123 and FLICA staining confirmed that both these AMB-treated blastospores and filamentous cells accumulated ROS and activated caspases, respectively—two classic markers of programmed cell death – and were undergoing cell death as revealed by staining with propidium iodide (Figure 1). With both markers, however, there were fewer marker-positive filamentous cells as compared to blastospore controls, suggesting that the former cell type was more resistant to AMB.

–

Next, we compared the viability of wild-type Candida albicans cells in the blastospore and filamentous forms when cultured in media containing 8 µg/ml AMB with control cultures grown in YPD alone. Clonogenic survival assays are routinely used to assay programmed cell death in yeast [10][23][24][40][41]. As shown in Figure 1C, hyphal cells had a higher viability when cultured in media containing AMB than their blastospore counterparts (p < 0.005). This data suggests that filamentation protects Candida cells from AMB-induced programmed cell death and that this type of programmed cell death is cell-type specific in yeast.

–

However, because hyphae were induced by culturing blastospores in media containing FBS [11], it is possible that the differences in clonogenic survival rate could be attributed to culture conditions—namely, the presence of FBS—rather than to filamentation. To rule out this alternative explanation for our observations, we repeated our assays with a filamentation induction protocol that used N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) instead of FBS [42][43]. As shown in Figure 1D, GlcNAc-induced filamentous cells were also more resistant than their blastospore counterparts to AMB-induced cell death. Still, it could be argued that the difference in survival rate observed between the two cell types was only due to the variable presence of either FBS or GlcNAc. To respond to this concern, we repeated our experiments with Can36, a SC5314-derived mutant yeast strain lacking CPH1 and EFG1, two putative transcription factors necessary for filamentation in Candida [12]. As expected, this strain was unable to undergo filamentation in media containing 10% FBS (Supplemental Figure 1). However, as shown in Figure 1E, the viability of the ΔΔcph1/cph1 efg1/efg1 mutant yeast cells cultured in FBS and exposed to AMB was indistinguishable from that of mutant yeast cells cultured in media with AMB alone. Finally, we repeated our assay a fourth time with CCF3, a SC5314-derived ΔΔflo8/flo8 strain that is also unable to undergo filamentation when cultured in FBS [10]. Again, this non-filamentous mutant was unable to survive when cultured in the presence of AMB regardless of whether or not it was first cultured in the presence of FBS (Figure 1F). Complementation of the ΔΔflo8/flo8 strain confirmed that this phenotype, along with the inability to undergo filamentation, are both dependent upon the null ΔΔflo8/flo8 mutation as others had previously shown [10]. Thus, we conclude that the resistance pattern noted in both non-filamentous mutants is not related to secondary effects of the mutations distinct from their inability to undergo filamentation, and that FBS itself is unable to protect yeast cells from AMB-induced programmed cell death. Together, these experiments suggest that filamentation protects yeast cells against AMB-induced programmed cell death.

–

To investigate the mechanism behind this anti-cell death phenomenon, we decided to focus on the yeast metacaspase, MCA1, a homolog of the mammalian caspases linked to apoptosis in metazoans. The MCA1 homolog in S. cerevisae, YCA1, has been implicated in programmed cell death: mutants lacking YCA1 in S. cerevisae exhibit lower levels of intracellular caspase activation and significantly decreased levels of programmed cell death when exposed to hyposomatic stress [32][44]. We compared the survival rate of the wildtype BWP17 blastospores and filaments with their BWP17-derived ΔΔmca1/mca1 mutant counterparts. Wildtype and all mca1 mutants were able to undergo filamentation when exposed to 10% FBS (Supplemental Figure 2). As shown in Figure 2, ΔΔmca1/mca1 blastospores and hyphal cells had indistinguishable survival rates when cultured in media containing AMB. This data suggests that MCA1 is involved in the resistance of filamentous cells to AMB-induced programmed cell death. Complementation of the null ΔΔmca1/mca1 mutant restored the original difference in viability that we had observed between blastospore and hyphal cells cultured in AMB-containing media, suggesting that the original ΔΔmca1/mca1 phenotype could be linked to the original loss-of-function mutation in MCA1. In sum, our data suggests that filamentation protects C. albicans cells from AMB induced cell death and that this phenotype is dependent upon the yeast metacaspase, MCA1. Given that MCA1 has previously been thought to have a pro-death function, it is not yet clear how Mca1p functions in this protective capacity in filamentous cells. However, it is intriguing that several recent papers have revealed that the Mca1p homolog has a non-death role in S. cerevisae and possibly, in C. albicans as well [36][45][46][47][48][49].

–

Finally, we wanted to determine if filamentation protected Candida cells from another anti-fungal drug known to induce programmed cell death. Thus, we compared the viability of blastospores and hyphal cells in media containing 0.05 µg/ml caspofungin (CAS), an echinocandin known to trigger cell death, in Candida albicans [22][23]. As shown in Figure 3, filamentation also appears to protect yeast cells from CAS-induced cell death suggesting the protective effects of filamentation may be a general phenomenon in Candida albicans. Watamoto et al. have proposed that filamentous Candida cells are resistant to AMB and to nystatin because they are able to form biofilms [17][50]. In light of our findings, we also propose that planktonic hyphal cells may in themselves be relatively more resilient to these drugs—and possibly other anti-fungal drugs as well—because of their heightened resistance to programmed cell death.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Media and Growth Conditions

C. albicans cells were grown in yeast extract/peptone/dextrose broth (YPD) made according to standard recipes [51]. Cells were inoculated from single colonies growing on YPD plates into 20 ml YPD and grown under shaking at 30°C until the culture attained an OD600 value of 2.00 A. Once the culture had reached OD600≈2.0 A, cells were harvested and then resuspended in fresh media at a concentration of 3×107 cells/ml (OD600≈1.26 A). For blastospore induction, cells from the original culture were resuspended in fresh YPD, transferred to a sterile flask, and then grown under shaking at 30°C for 3 hours. For hyphal induction, harvested cells were resuspended in either YPD + 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone) pre-warmed to 37°C (YPD + FBS) or YPD + N-acetylglucosamine at a concentration of 0.5 g/l GlcNAc (Sigma-Aldrich; YPD+GlcNAc), transferred into a fresh flask, and placed in an incubator with shaking at 37°C for 3 hours [11][12][42][43][52].

–

Viability Assays

Blastospores and hyphal cells were harvested and resuspended at a concentration of 1×107 cells/ml in fresh YPD, and placed in 15 ml conical tubes. Cells were then exposed to AMB (Sigma) at a concentration of 5 µg/ml or 8 µg/ml (from a 1 mg/ml stock in dimethyl sulfoxide) for 3 hours, with shaking, at 25°C [24]. At t=0, 1, 2, and 3 hours of AMB exposure, serial dilutions of the cell cultures were done on YPD plates. The plates were then placed in a 30°C incubator for 24 to 48 hours, or until single colonies were distinguishable. Colonies for each time point were counted and then compared as a percentage of the number of colonies that formed on the t=0 plate. For each time point, three independent cultures were tested. Notably, we confirmed our clonogenic assays by directly visualizing dead filamentous cells using propidum iodide (50 μg/ml) and then counting them with a Zeiss LSM700 fluorescent microscope. For the experiments with caspofungin, blastospores and filaments were cultured in the drug at a concentration of 0.05 μg/ml (from a 1 mg/ml stock in dimethyl sulfoxide) for 3 hours, with shaking, at 25°C. The viability of the cells was determined by culturing them in propidium iodide (50 μg/ml) and then counting them visually with a Zeiss LSM700 fluorescent microscope. Again, three independent cultures were tested, and at least 300 cells were counted for each determination. Statistical significance for all experiments was determined with the unpaired Student’s t-test.

–

In Vivo Detection of ROS Accumulation and Caspase Activation

Intracellular ROS accumulation was examined after treatment with AMB or caspofungin using 5 μg/ml of dihydrorhodamine 123 (DH123; Sigma Aldrich) [24]. Activated caspases were detected in C. albicans cells after treatment with AMB or CAS using a FLICA apoptosis detection kit (ImmunoChemistry Technologies, LLC) according to the manufacturer’s specifications [38]. After exposure to either DHR123 or the FLICA reagent, C. albicans cells were harvested and examined using a Zeiss 700 Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope.

References

- J. Guinea, "Global trends in the distribution of Candida species causing candidemia.", Clinical microbiology and infection : the official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, 2014. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24506442

- A. Cassone, and R. Cauda, "Candida and candidiasis in HIV-infected patients: where commensalism, opportunistic behavior and frank pathogenicity lose their borders.", AIDS (London, England), 2012. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22472853

- P.A. Grossi, "Clinical aspects of invasive candidiasis in solid organ transplant recipients.", Drugs, 2009. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19877729

- G. Sensoy, and N. Belet, "Invasive Candida infections in solid organ transplant recipient children.", Expert review of anti-infective therapy, 2011. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21417871

- M. Pfaller, D. Neofytos, D. Diekema, N. Azie, H. Meier-Kriesche, S. Quan, and D. Horn, "Epidemiology and outcomes of candidemia in 3648 patients: data from the Prospective Antifungal Therapy (PATH Alliance®) registry, 2004-2008.", Diagnostic microbiology and infectious disease, 2012. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23102556

- M. Mikulska, V. Del Bono, S. Ratto, and C. Viscoli, "Occurrence, presentation and treatment of candidemia.", Expert review of clinical immunology, 2012. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23167687

- M. Huang, and K.C. Kao, "Population dynamics and the evolution of antifungal drug resistance in Candida albicans.", FEMS microbiology letters, 2012. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22540673

- M.A. Pfaller, "Antifungal drug resistance: mechanisms, epidemiology, and consequences for treatment.", The American journal of medicine, 2012. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22196207

- M. Brennan, D.Y. Thomas, M. Whiteway, and K. Kavanagh, "Correlation between virulence of Candida albicans mutants in mice and Galleria mellonella larvae.", FEMS immunology and medical microbiology, 2002. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12381467

- F. Cao, S. Lane, P.P. Raniga, Y. Lu, Z. Zhou, K. Ramon, J. Chen, and H. Liu, "The Flo8 transcription factor is essential for hyphal development and virulence in Candida albicans.", Molecular biology of the cell, 2005. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16267276

- D. Kadosh, and A.D. Johnson, "Induction of the Candida albicans filamentous growth program by relief of transcriptional repression: a genome-wide analysis.", Molecular biology of the cell, 2005. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15814840

- H.J. Lo, J.R. Köhler, B. DiDomenico, D. Loebenberg, A. Cacciapuoti, and G.R. Fink, "Nonfilamentous C. albicans mutants are avirulent.", Cell, 1997. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9298905

- R. Pukkila-Worley, A.Y. Peleg, E. Tampakakis, and E. Mylonakis, "Candida albicans hyphal formation and virulence assessed using a Caenorhabditis elegans infection model.", Eukaryotic cell, 2009. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19666778

- P. Staib, A. Binder, M. Kretschmar, T. Nichterlein, K. Schröppel, and J. Morschhäuser, "Tec1p-independent activation of a hypha-associated Candida albicans virulence gene during infection.", Infection and immunity, 2004. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15039365

- B.B. Fuchs, J. Eby, C.J. Nobile, J.B. El Khoury, A.P. Mitchell, and E. Mylonakis, "Role of filamentation in Galleria mellonella killing by Candida albicans.", Microbes and infection, 2010. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20223293

- L. Laforet, I. Moreno, R. Sánchez-Fresneda, M. Martínez-Esparza, J.P. Martínez, J. Argüelles, P.W.J. de Groot, and E. Valentín-Gomez, "Pga26 mediates filamentation and biofilm formation and is required for virulence in Candida albicans.", FEMS yeast research, 2011. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21439008

- T. Watamoto, L.P. Samaranayake, H. Egusa, H. Yatani, Y.H. Samaranayke, and C.J. Seneviratne, "Susceptibility of Candida albicans filamentation-defective mutants to clinical biocides.", The Journal of hospital infection, 2010. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20061059

- T.R. O'Meara, A.O. Veri, T. Ketela, B. Jiang, T. Roemer, and L.E. Cowen, "Global analysis of fungal morphology exposes mechanisms of host cell escape.", Nature communications, 2015. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25824284

- S.M. Noble, S. French, L.A. Kohn, V. Chen, and A.D. Johnson, "Systematic screens of a Candida albicans homozygous deletion library decouple morphogenetic switching and pathogenicity.", Nature genetics, 2010. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20543849

- M. Ramsdale, "Programmed cell death in pathogenic fungi.", Biochimica et biophysica acta, 2008. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18294459

- B. Almeida, A. Silva, A. Mesquita, B. Sampaio-Marques, F. Rodrigues, and P. Ludovico, "Drug-induced apoptosis in yeast.", Biochimica et biophysica acta, 2008. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18252203

- C. Chin, . , F. Donaghey, K. Helming, M. McCarthy, S. Rogers, N. Austriaco, . , and . , "Deletion of AIF1 but not of YCA1/MCA1 protects Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Candida albicans cells from caspofungin-induced programmed cell death", Microbial Cell, vol. 1, pp. 58-63, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.15698/mic2014.01.119

- B. Hao, S. Cheng, C.J. Clancy, and M.H. Nguyen, "Caspofungin kills Candida albicans by causing both cellular apoptosis and necrosis.", Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy, 2012. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23114781

- A.J. Phillips, I. Sudbery, and M. Ramsdale, "Apoptosis induced by environmental stresses and amphotericin B in Candida albicans.", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2003. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14623979

- S. Lin, and N. Austriaco, "Aging and cell death in the other yeasts, Schizosaccharomyces pombe and Candida albicans.", FEMS yeast research, 2013. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24205865

- J.F. Kerr, A.H. Wyllie, and A.R. Currie, "Apoptosis: a basic biological phenomenon with wide-ranging implications in tissue kinetics.", British journal of cancer, 1972. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4561027

- J.C. Ameisen, "On the origin, evolution, and nature of programmed cell death: a timeline of four billion years.", Cell death and differentiation, 2002. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11965491

- C.M. Zmasek, and A. Godzik, "Evolution of the animal apoptosis network.", Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology, 2013. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23457257

- X. Teng, and J.M. Hardwick, "Cell death in genome evolution.", Seminars in cell & developmental biology, 2015. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25725369

- D. Carmona-Gutierrez, T. Eisenberg, S. Büttner, C. Meisinger, G. Kroemer, and F. Madeo, "Apoptosis in yeast: triggers, pathways, subroutines.", Cell death and differentiation, 2010. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20075938

- Q. Liang, W. Li, and B. Zhou, "Caspase-independent apoptosis in yeast.", Biochimica et biophysica acta, 2008. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18358844

- F. Madeo, D. Carmona-Gutierrez, J. Ring, S. Büttner, T. Eisenberg, and G. Kroemer, "Caspase-dependent and caspase-independent cell death pathways in yeast.", Biochemical and biophysical research communications, 2009. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19250922

- A.J. Munoz, K. Wanichthanarak, E. Meza, and D. Petranovic, "Systems biology of yeast cell death.", FEMS yeast research, 2012. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22188402

- A.H. Wong, C. Yan, and Y. Shi, "Crystal structure of the yeast metacaspase Yca1.", The Journal of biological chemistry, 2012. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22761449

- D. Wilkinson, and M. Ramsdale, "Proteases and caspase-like activity in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae.", Biochemical Society transactions, 2011. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21936842

- T. Léger, C. Garcia, M. Ounissi, G. Lelandais, and J. Camadro, "The metacaspase (Mca1p) has a dual role in farnesol-induced apoptosis in Candida albicans.", Molecular & cellular proteomics : MCP, 2014. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25348831

- R. Strich, "Programmed Cell Death Initiation and Execution in Budding Yeast.", Genetics, 2015. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26272996

- M.E. Shirtliff, B.P. Krom, R.A.M. Meijering, B.M. Peters, J. Zhu, M.A. Scheper, M.L. Harris, and M.A. Jabra-Rizk, "Farnesol-induced apoptosis in Candida albicans.", Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy, 2009. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19364863

- W.A. Fonzi, and M.Y. Irwin, "Isogenic strain construction and gene mapping in Candida albicans.", Genetics, 1993. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8349105

- A.M. Aerts, D. Carmona-Gutierrez, S. Lefevre, G. Govaert, I.E.J.A. François, F. Madeo, R. Santos, B.P.A. Cammue, and K. Thevissen, "The antifungal plant defensin RsAFP2 from radish induces apoptosis in a metacaspase independent way in Candida albicans.", FEBS letters, 2009. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19596007

- K.T. Nguyen, P. Ta, B.T. Hoang, S. Cheng, B. Hao, M.H. Nguyen, and C.J. Clancy, "Anidulafungin is fungicidal and exerts a variety of postantifungal effects against Candida albicans, C. glabrata, C. parapsilosis, and C. krusei isolates.", Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy, 2009. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19364856

- J. Bauer, and J. Wendland, "Candida albicans Sfl1 suppresses flocculation and filamentation.", Eukaryotic cell, 2007. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17766464

- J.M. Hornby, E.C. Jensen, A.D. Lisec, J.J. Tasto, B. Jahnke, R. Shoemaker, P. Dussault, and K.W. Nickerson, "Quorum sensing in the dimorphic fungus Candida albicans is mediated by farnesol.", Applied and environmental microbiology, 2001. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11425711

- C. Mazzoni, and C. Falcone, "Caspase-dependent apoptosis in yeast.", Biochimica et biophysica acta, 2008. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18355456

- Y. Cao, S. Huang, B. Dai, Z. Zhu, H. Lu, L. Dong, Y. Cao, Y. Wang, P. Gao, Y. Chai, and Y. Jiang, "Candida albicans cells lacking CaMCA1-encoded metacaspase show resistance to oxidative stress-induced death and change in energy metabolism.", Fungal genetics and biology : FG & B, 2008. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19049890

- M. Erhardt, R.D. Wegrzyn, and E. Deuerling, "Extra N-terminal residues have a profound effect on the aggregation properties of the potential yeast prion protein Mca1.", PloS one, 2010. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20360952

- R.E.C. Lee, S. Brunette, L.G. Puente, and L.A. Megeney, "Metacaspase Yca1 is required for clearance of insoluble protein aggregates.", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2010. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20624963

- A. Shrestha, L.G. Puente, S. Brunette, and L.A. Megeney, "The role of Yca1 in proteostasis. Yca1 regulates the composition of the insoluble proteome.", Journal of proteomics, 2013. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23376483

- S.M. Hill, X. Hao, B. Liu, and T. Nyström, "Life-span extension by a metacaspase in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae.", Science (New York, N.Y.), 2014. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24855027

- T. Watamoto, L.P. Samaranayake, J.A.M.S. Jayatilake, H. Egusa, H. Yatani, and C.J. Seneviratne, "Effect of filamentation and mode of growth on antifungal susceptibility of Candida albicans.", International journal of antimicrobial agents, 2009. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19376687

- D. Bruke, D. Amber, and J. Strathern, " Methods in Yeast Genetics: A Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Course Manual.", Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY., 2005.

- K.L. Lee, H.R. Buckley, and C.C. Campbell, "An amino acid liquid synthetic medium for the development of mycelial and yeast forms of Candida Albicans.", Sabouraudia, 1975. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/808868

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

![]() Download Supplemental Information

Download Supplemental Information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Valmik K. Vyas and Gerald Fink (Massachusetts Institute of Technology), Haoping Liu (Univer-sity of California, Irvine), and Renata Santos (Institut Jacques Monod) for strains, and Richard Bennett (Brown University) for technical advice. Our laboratory is supported by the fol-lowing grants awarded to N. Austriaco: NIGMS R15 GM094712, NIGMS R15 GM110578, NSF MRI-R2 0959354, and NIH Grant 8 P20 GM103430-14 to the Rhode Island INBRE Program.

COPYRIGHT

© 2016

Filamentation protects Candida albicans from amphotericin B-induced programmed cell death via a mechanism involving the yeast metacaspase, MCA1 by Laprade et al. is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.