Research Articles:

Microbial Cell, Vol. 5, No. 8, pp. 371 - 384; doi: 10.15698/mic2018.08.642

Importance of polyphosphate in the Leishmania life cycle

1 Department of Biochemistry, University of Lausanne, Epalinges, Switzerland.

2 Department of Molecular Microbiology, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri, United States of America.

Keywords: polyphosphate, VTC4, Leishmania, life cycle, infectivity, temperature stress.

Abbreviations:

BSF - blood stream form,

LPG – lipophosphoglycan,

PNA - peanut agglutinin,

polyP – polyphosphate,

SSU - small subunit ribosomal RNA.

Received originally: 08/02/2018 Received in revised form: 29/05/2018

Accepted: 01/06/2018

Published: 22/06/2018

Correspondence:

Nicolas Fasel, Department of Biochemistry, University of Lausanne, Ch. des Boveresses 155, 1066 Epalinges, Switzerland; Tel: +41 21 6925732; Fax: +41 21 6925705; nicolas.fasel@unil.ch

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Kid Kohl, Haroun Zangger, Matteo Rossi, Nathalie Isorce, Lon-Fye Lye, Katherine L. Owens, Stephen M. Beverley, Andreas Mayer and Nicolas Fasel (2018). Importance of Polyphosphate in the Leishmania life cycle. Microbial Cell 5(8): 371-384. doi: 10.15698/mic2018.08.642

Abstract

Protozoan parasites contain negatively charged polymers of a few up to several hundreds of phosphate residues. In other organisms, these polyphosphate (polyP) chains serve as an energy source and phosphate reservoir, and have been implicated in adaptation to stress and virulence of pathogenic organisms. In this study, we confirmed first that the polyP polymerase vacuolar transporter chaperone 4 (VTC4) is responsible for polyP synthesis in Leishmania parasites. During Leishmania in vitro culture, polyP is accumulated in logarithmic growth phase and subsequently consumed once stationary phase is reached. However, polyP is not essential since VTC4-deficient (vtc4–) Leishmania proliferated normally in culture and differentiated into infective metacyclic parasites and into intracellular and axenic amastigotes. In in vivo mouse infections, L. major VTC4 knockout showed a delay in lesion formation but ultimately gave rise to strong pathology, although we were unable to restore virulence by complementation to confirm this phenotype. Knockdown of VTC4 did not alter the course of L. guyanensis infections in mice, suggesting that polyP was not required for infection, or that very low levels of it suffice for lesion development. At higher temperatures, Leishmania promastigotes highly consumed polyP, and both knockdown or deletion of VTC4 diminished parasite survival. Thus, although polyP was not essential in the life cycle of the parasite, our data suggests a role for polyP in increasing parasite survival at higher temperatures, a situation faced by the parasite when transmitted to humans.

INTRODUCTION

Leishmania parasites can cause leishmaniasis, a disease affecting over 12 million people in 98 countries in tropical and subtropical regions [1] and are responsible for different immuno-pathologies: cutaneous, mucosal and visceral, depending mainly on the infecting species. As part of their life cycle, Leishmania need to switch between two different forms, which allow them to better adapt to each host. These protozoan parasites live either as intracellular amastigotes in the phagolysosome of human macrophages or as extracellular flagellated promastigotes in different sand fly species (e.g. Phlebotomus or Lutzomyia). In their insect vector, after a blood meal, Leishmania differentiate from amastigotes into proliferating procyclic promastigotes, which further differentiate into stationary infectious metacyclic promastigotes [2]. While cycling between two hosts, the parasites are exposed to major environmental changes such as pH, temperature, reactive oxygen species, nutrient and oxygen availabilities. Polymers of inorganic phosphate (polyP) might play a role in adaptation to these drastic changes of environment as they have been implicated in stress tolerance in several other organisms [3].

–

Many bacterial, archaeal, fungal, protozoan, plant or animal organisms contain polyP. These are linear polymers of inorganic phosphate composed of a few up to many hundreds of orthophosphate residues linked by phosphoric anhydride bonds. Despite their prevalence, polyPs are understudied and they have long been dismissed as ‘molecular fossils’ which serve as a source of phosphate and energy. However, we now begin to understand that polyP is an active element of metabolism that contributes to adaptations to stress and also to virulence. In prokaryotes, for instance, polyP synthesis is crucial for Escherichia coli transition from active growth into stationary phase and for cell survival under nutrient starvation, heat, oxidative or osmotic stress and UV irradiation (reviewed in [3]). PolyP also influences bacterial gene transcription, motility, quorum sensing, virulence and the formation of ion channels and biofilms (reviewed in [4][5][6][7]). In the absence of the polyP kinase 1 (PPK1), some bacterial pathogens display growth disorders, loss of viability, intolerance to acid and heat and diminished invasiveness into epithelial cells [3][8][9], some of which may be related to the capacity of polyP to chaperone proteins [10]. In mammals, the presence of polyP chains has been discovered much later, probably due to its lower concentration. PolyP functions in mammals have been related to cancer [1][11], apoptosis [12], bone mineralization [13], osteoblast function [14], fibroblast growth stimulation [15] and energy metabolism [16], to which much attention has been drawn to lately for their pro-coagulant and pro-inflammatory effects [17][18].

–

In bacteria, polyP is mainly synthesized by two polyP kinases, PPK1 and PPK2. PPK1 is responsible for the major portion of polyP in the cell as it catalyzes the transfer of the gamma-phosphate of ATP to the nascent polyP chain. Even though this reaction is reversible it favors the synthesis of polyP. PPK2 can synthesize polyP from GTP but it favors the reverse reaction of polyP degradation [19][20]. No homologs of the PPKs could be found in eukaryotes, except for the slime mold Dictyostelium discoideum. In the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, a large number of genes are required for the synthesis of polyP [21][22], among which is a polyP polymerase, named vacuolar transporter chaperone 4 (Vtc4), which represents the first eukaryotic-specific polyP synthase described [23]. Vtc4 is a transmembrane protein that forms different complexes with other Vtc proteins, either in the combination of Vtc1, Vtc2 and Vtc4 or Vtc1, Vtc3 and Vtc4 [23][24][25][26]. These Vtc complexes synthesize polyP from nucleotide triphosphates and translocate it at the same time into the acidocalcisome-like vacuoles, where polyP is sequestered in order to avoid its toxic effects in the cytosol. Moreover, Vtc complexes can be stimulated by association with a fifth subunit, Vtc5, or by binding of inositol pyrophosphates to their SPX domains [27][28][29]. In yeast, Vtc deficiency affects the ability of the cell to grow under phosphate-limiting or metal-limiting conditions [23][30], mildly reduces vacuolar proton pump function and influences organelle biogenesis through cargo traffic between the ER and Golgi, vacuolar fusion and micro-autophagy [24][25][31]. As the polyP polymerases in higher eukaryotes are still unknown, it remains difficult to experimentally interfere with polyP levels and explore polyP functions in animals and plants.

–

In trypanosomatid parasites, such as Trypanosoma or Leishmania, polyP is highly concentrated in acidocalcisomes, which are acidic organelles that besides the negatively charged polyP, also contain cations (Ca2+, Mg2+, Na+, K+, Zn2+, Fe2+) and basic amino acids (mainly arginine and lysine) [32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39]. Accumulating data suggests that polyP and acidocalcisomes in parasites play an important role for adaptation to stresses and affect disease outcome [32][33][35][36][40][41][42][43][44][45]. Although several studies have been performed on acidocalcisomes in Trypanosoma, little is known about polyP expression and function in Leishmania. In this study, we investigated whether polyP plays a role in the life cycle of Leishmania parasites and in its survival under stress conditions.

RESULTS

Identification of the VTC4 gene in Leishmania

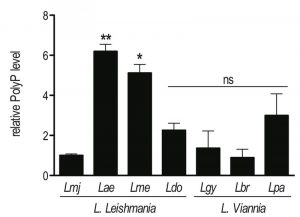

In order to investigate the role of polyP in the life cycle of Leishmania, we first identified the enzyme responsible for polyP synthesis and confirmed its presence in different Leishmania species. Knowing that VTC4 is responsible for polyP synthesis in yeast and T. brucei, we searched for vtc4 homologues in L. major. Database mining of the L. major genome for yeast or T. brucei VTC homologues revealed a single gene coding for VTC4 localized on chromosome 9 (LmjF09.0220). The LmjVTC4 open reading frame (ORF) encodes an 813 amino acid protein with a predicted molecular mass of 93.4 kDa. Using this information, we also identified VTC4 in other Leishmania species and cloned it from the L. guyanensis genome (GenBank access number: MF572933). Using alignments by ClustalW within Jalview [46] [47], the LmjVTC4 amino acid sequence appears quite conserved with respect to VTC4 from other Leishmania and Trypanosoma species: 97% sequence identity with L. infantum, 95% with L. mexicana, 88% with L. braziliensis and L. guyanensis, and 67% with T. brucei and T. cruzi (Fig. S1). We also used an enzymatic assay to test for the presence of polyP in different Leishmania species of two distinct subgenera. Using this assay, we confirmed that polyP was present in every Leishmania species analyzed, albeit at significantly different abundance (Fig. 1). However, we could not correlate the different levels of polyP to a specific Leishmania subgenus (L. Leishmania or L. Viannia).

–

Decreased mRNA and polyP levels in VTC4 knockdown L. guyanensis parasites

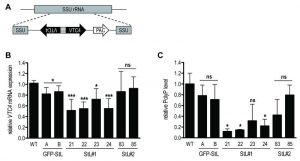

To confirm the relation between VTC4 and polyP synthesis in Leishmania parasites, VTC4 was knocked down in L. guyanensis, taking advantage of the presence of the RNA degradation machinery in the Leishmania (Viannia) subgenus [48][49]. We used the RNA interference (RNAi) approach to generate VTC4 knockdown L. guyanensis in a single round of transfection. For this purpose, two stem-loop (hairpin) RNAi constructs were generated using the pIR integrating transfection vectors that target either a region at the beginning (193 – 788, referred to as StL#1) or at the center (867 – 1963, referred to as StL#2) of the L. guyanensis VTC4 ORF (Fig. S2). These stem loop constructs contained two copies of the targeted region in an inverted orientation separated by a short loop (Fig. 2A), and were flanked by Leishmania sequences required for efficient 5’ and 3’ end mRNA formation, as well as a selectable drug resistance gene [48]. Upon parasite transfection, the linearized DNA was integrated into the small subunit ribosomal RNA (SSU) locus. As a control, parasites with a GFP targeting stem loop (GFP-StL) were generated [48][50]. Clones were selected due to their drug resistance and DNA integration was confirmed by PCR (Fig. S2B, C).

In order to investigate the knockdown efficiency, we performed a quantitative real time (qRT-) PCR on VTC4 transcripts [50]. Relative expression of VTC4 mRNA levels were significantly decreased in StL#1 transfected clones, while there was no decrease in StL#2 transfectants (Fig. 2B). Although Lye et al. observed more than 10-fold mRNA reduction in their Luciferase and GFP knockdowns [48], we detected a less than 2-fold reduction for StL#1 in the same strain of L. guyanensis. qRT-PCR can, however, detect RNA degradation products which can accumulate even though they are non-functional and thus underestimate the effect on the protein level [48][51].

–

We measured presumptive VTC4 activity by extracting and quantifying polyP of logarithmic phase RNAi transfectants. The polyP levels of StL#1 transfectants were decreased three- to five-fold, whereas the effects in StL#2 and in GFP-StL transfectant controls were not statistically significant (Fig. 2C), thus confirming the qRT-PCR data (Fig. 2B). As variability in efficiency amongst RNAi constructs is not uncommon, for subsequent studies we used only the two StL#1 transfectants (clones 21 and 22) showing the strongest knockdown.

–

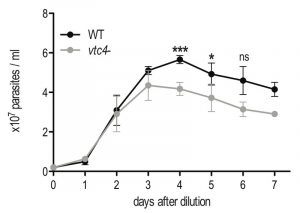

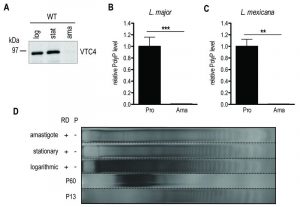

vtc4– L. major is devoid of short-chain polyP, displays normal promastigote growth and differentiates into metacyclic promastigotes

We first measured polyP levels and lengths during the in vitro transition of L. major and L. mexicana promastigotes from logarithmic into stationary phase (Fig. 3) using a protocol detecting mainly short-chain polyP (< 300 residues). From a stationary phase culture, parasites were diluted to a concentration of 5 x 105 parasites/ml, cultured over 7 days and cell density was measured every day (Fig. 3A, C). In addition, polyP was extracted, digested and quantified at each time point. In promastigotes of both Leishmania species tested, polyP was most abundant in late logarithmic growth phase promastigotes (day 3 post dilution), while it gradually decreased overtime in long term stationary phase cultures (day 4 to 7 post dilution) (Fig. 3B, D), suggesting that polyP synthesis occurred mainly in proliferating parasites, and consumed when stationary parasites were maintained in culture for a long period. To test whether VTC4 was still expressed in stationary phase parasites, and to confirm its absence in vtc4– parasites in parallel, we used polyclonal antibodies against the L. major protein for use in western blotting [30]. The central domain (a.a. 202 – 504) of LmjVTC4 (cd-LmjVTC4) was expressed in bacteria and used for rabbit immunization. In contrast to polyP, VTC4 levels stayed constant during the entire promastigote stage, suggesting that VTC4 might be inactivated by post-translational regulation, or the degradation of polyP chains might be increased during stationary phase (Fig. 3E). As controls for our antibody, we previously used vtc4– parasites and confirmed the absence of VTC4 in vtc4– parasites [30].

–

Although VTC4 was essential for polyP synthesis in Leishmania, and apparently no other enzyme complemented its function, vtc4– promastigotes had a morphology similar to WT and proliferated in culture similarly to WT promastigotes, demonstrating that VTC4 was not essential for promastigote viability and proliferation in vitro. However, WT and vtc4– clones did not reach the same cell density in culture (Fig. 4) suggesting that VTC4 could be important for parasite survival in nutrient-limited conditions.

–

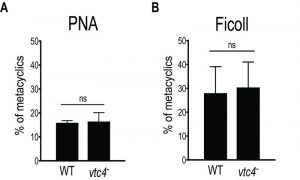

Since polyP is important in the transition from active growth into stationary phase in bacteria [3] and play a role in parasite virulence [32][36][52][53], we explored whether vtc4– parasites were able to differentiate into infectious metacyclic promastigotes. In L. major, metacyclogenesis is accompanied by changes in parasite morphology, size and in the composition of the parasite glycocalyx, including lipophosphoglycan (LPG) [54][55]. To evaluate the efficiency of metacyclogenesis, stationary promastigotes were fractionated by applying two different methods: a peanut agglutinin (PNA) assay, in which only procyclic LPG binds to lectins [56], and a LPG-independent Ficoll gradient centrifugation method [57]. Both methods showed no significant difference in the percentage of metacyclics between vtc4– and WT parasites (Fig. 5A, B), suggesting that polyP is not required for Leishmania development into metacyclic stationary promastigotes.

–

Absence of VTC4 expression and polyP in the amastigote stage

Subsequently, we determined whether VTC4 was expressed in the amastigote stage by immunoblotting using an anti-VTC4 antibody. VTC4 was almost completely absent from amastigotes isolated from mouse footpad lesions (Fig. 6A). Accordingly, L. major amastigotes isolated from lesions, as well as L. mexicana axenic amastigotes obtained after 5 days of in vitro differentiation contained very low amounts of polyP in comparison to proliferating promastigotes (Fig. 6B and C). We confirmed this result by PAGE of polyP chains from logarithmic growth phase (day 3 post dilution) or stationary phase (day 6 post dilution) promastigotes, and from L. major amastigotes isolated from macrophages, visualizing polyP abundance by negative DAPI staining. Polyphosphates were present in relatively high amounts in day 3 logarithmic promastigotes but almost absent in day 6 stationary phase promastigotes and in amastigotes, where mainly short-chain polyphosphates were detectable (Fig 6D). Vtc4– cells contained neither short nor long-chain polyP, suggesting that LmVtc4 may be the sole enzyme synthesizing polyP in this organism, at least under the growth conditions tested here. However, we cannot exclude the presence of much longer chains, which might exist [58] but may have escaped our assay.

–

Taken together, these data show that long-chain polyP accumulated during the proliferating logarithmic phase but decreased during long term culture of stationary parasites. Long-chain polyP was almost absent from amastigotes, which however, had similar amounts of shorter-chain polyP as the promastigotes. These data suggest that polyP could be important in the first days for parasites to replicate and to establish an efficient infection as shown previously [30] but not for the differentiation into amastigotes and the development of footpad lesions.

–

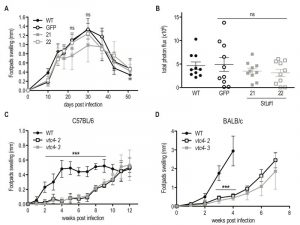

Relevance of VTC4 in infections in vivo

To investigate whether polyP plays a role during in vivo infection we infected mouse footpads with L. guyanensis VTC4 knockdown (StL#1) or L. major knockout (vtc4–) parasites and monitored footpad swelling on a weekly basis as a proxy for progression of the infection. The L. guyanensis M4147 WT line contains an integrated firefly luciferase gene (LUC), allowing parasite load to be quantified by bioluminescent imaging [48]. We used the C57BL/6 mouse model, in which L. guyanensis induces self-healing footpad swelling [59]. Infection with WT and the GFP-StL transfectant induced similar footpad swelling and parasite burden (Fig. 7A, B), peaking around 30 days post-infection and healing a few weeks later. VTC4 knockdown with StL#1 showed little effect, with clone 22 showing a profile identical to WT and clone 21 showing a small, statistically not significant, effect. Thus, a 5- to 10-fold reduction in polyP levels (Fig. 2C) produced little effect on parasite infectivity (Fig. 7A and B).

For L. major, we used the self-healing C57BL/6 as well as the susceptible BALB/c mouse models. vtc4– L. major infected mice showed an important delay of several weeks before developing footpad lesions in the C57BL/6 as well as the BALB/c model (Fig. 7C and D). However, in all infections, parasites finally replicated and infectious parasites could be recovered from the footpad. Even though the complemented vtc4–/+VTC4 cell line recovered polyp synthesis, this did not restore its ability to rapidly induce lesions in mice (data not shown), thus preventing us from confirming a role of polyP in the course of the infection. The cells might have adapted to the loss of VTC4 by second site mutations or genome rearrangements, leading to suppressor mutants that behave differently from the original WT.

–

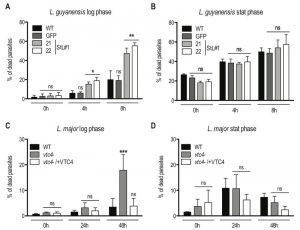

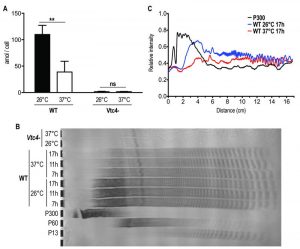

Absence of VTC4 and polyP lead to an increased sensitivity to heat shock

Next, we investigated whether polyP has an impact on parasite survival under different stress conditions encountered by Leishmania parasites during its life cycle, such as sudden increases of temperature. Parasites were grown in complete medium at 26°C and then split into two groups, of which one was exposed to 37°C, while a control was kept at 26°C. Parasite resistance was monitored by measuring cell death via propidium iodide staining at different time points. To better assess the effect of different polyP levels, both logarithmic growth phase (day 3 post dilution) and late stationary phase (day 6 post dilution) promastigotes were used. Presence of polyP increased the resistance to heat stress (37°C) of the polyP-rich logarithmic phase promastigotes from both L. major and L. guyanensis (Fig. 8A and C). PolyP-deficient Leishmania displayed an approximate 3-fold increase in cell death compared to controls, highlighting a protective role of polyP before parasites reached the stationary phase. By contrast, no significant effect on cell survival was observed in stationary phase promastigotes (Fig. 8B, D), which contain low amounts of polyP (Fig. 3B).

Interestingly, L. guyanensis was much more sensitive to heat stress than L. major, with all clones already showing an increased frequency of cell death after 8 hours, while L. major was not affected during the first 24 hours. We quantified polyP in heat-treated logarithmic phase promastigotes and observed that, when maintained for several hours at 37°C, polyP became less abundant and the length of the polymer chains decreased in comparison to parasites cultured at 26°C (Fig. 9A, B), suggesting that longer-chain polyP is consumed under these conditions. A quantification of lanes of using ImageJ (Fig. 9C) showing a decrease in length of longer-chain polyP supports this hypothesis. This strengthens the correlation between polyP level and resistance to temperature stress. These results are consistent with our previous observation that L. major vtc4– parasites still differentiated into amastigotes but survived less than WT within macrophages [30]. Thus, some parasites are killed and survivors are blocked in their replication till they are fully adapted to their new milieu. Once differentiated into amastigotes, our data showed that parasites do not require polyP to survive and to replicate in their host.

DISCUSSION

Our study suggests that Leishmania VTC4 synthesizes long-chain polyP and that likely no other enzyme complements for this function. This differs from T. brucei, where VTC4 only provides a portion of the short-chain polyP since the conditional VTC4 knockout of the blood stream form (BSF) resulted only in a 35% decrease in short-chain polyP but no significant changes in long-chain polyP [36]. Furthermore, vtc4– L. major promastigotes could be cultured in vitro, indicating that VTC4, and thereby also polyP, are not essential at this stage. In contrast, T. brucei conditional VTC4 knockout BSF shows a progressive decrease in growth rate relative to the WT [36]. These differences between trypanosomatids in terms of polyP regulation and function could be related to the fact that T. brucei resides extracellularly in both its insect and mammalian hosts, whereas Leishmania parasites proliferate inside the mammalian macrophage and possibly acquire phosphate from the host cell. Albeit present in all the Leishmania species analyzed, polyP abundance varies substantially between them (Fig. 1), underscoring the different synthesis abilities or consumption of this polymer.

–

Similar to previous observations in bacteria [60] and yeast [4][61], we found that polyP pools were highest at the end of the logarithmic phase and started to decrease once Leishmania promastigotes reached the stationary phase. Moreover, in the intracellular amastigote form, we detected only low amounts of polyP and VTC4, suggesting that, once the infection was established, amastigotes might not require high steady-state amounts of polyP to survive in their host. This could possibly explain why VTC4 knockdown or knockout cell lines are still able to establish an infection in vivo. This observation differs from what was previously observed in T. brucei, where infection with conditional VTC4 knockout parasites induced lower parasitemia in the blood and 50% less death in BALB/c mice [36]. In this latter case, the authors propose that infectivity is impaired through an increased susceptibility to osmotic shock, which results from a lack of polyP in Trypanosoma [37][42][62][63]. As opposed to BSF Trypanosoma, Leishmania thrives intracellularly and osmoprotective roles of polyP might hence be less relevant in Leishmania than in Trypanosomes.

–

From the different stress conditions that we tested on Leishmania promastigotes (e.g. H2O2, phosphate buffered saline in the presence or absence of glucose and low pH) (data not shown), only heat shock at 37°C showed a polyP-related effect. PolyP-deficient L. major and polyP-low L. guyanensis were both more sensitive to increased temperature than the respective WT controls. However, the mechanism by which polyP promotes survival at high temperature remains unclear. Studies reported a rapid increase in cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations during physiological heat shock at 34 and 37°C, and suggest that this Ca2+ uptake is required for promastigote thermotolerance and differentiation into amastigotes [64][65]. Since polyP complexes cations in acidocalcisomes [35][39][66], it might be required to store the absorbed Ca2+ that could then be released upon heat shock and increase thermotolerance. An alternative possibility is provided by the chaperone-like effects of polyphosphates, which counteract protein inactivation and aggregation upon heat stress [10]. However, experiments on the solubility of proteins between WT and vtc4- parasites did not provide any evidence for such a possibility (H. Z and N.F, unpublished results).

–

The intracellular proliferation of Leishmania in the mammalian host comes with specific challenges, and polyP could play an important role in the first hours of infection, perhaps to facilitate the transition phase upon phagocytosis, during which the parasite must adapt to a radically different environment. In fact, inside phagosomes, Leishmania are exposed to an acidic pH and have restricted access to numerous nutrients, including metal ions, such as Mg2+, which can limit parasite growth inside the phagolysosome [67][68][69]. Recent studies in Saccharomyces cerevisiae showed that this organism relies on polyP in order to grow under conditions of limited bioavailability of Mg2+ [30]. The polyP stored in the acidocalcisome-like vacuoles may then be used as an immobilized chelator that filters ions from the environment. Interestingly, also Leishmania promastigotes lacking VTC4 and polyP grow poorly in low-Mg2+ media [70], suggesting that also in this organism polyP might be involved in extracting Mg2+ from the environment or in establishing sufficiently large reserves to support proliferation for a number of divisions in metal-poor environments. This could be relevant upon phagocytosis by a macrophage, as we previously showed that vtc4– Leishmania proliferate significantly less than WT within macrophages [30].

–

It should also not be neglected that Leishmania resides in two hosts. We found that polyP levels were highest at the end of the proliferating promastigote phase, which physiologically occurs in the sand fly, suggesting that polyP might be required for survival in the insect gut or for preparing the parasite for its next host. For instance, sand flies are mostly resident in tropical and subtropical regions where temperatures can reach high values and fluctuate daily (e.g. 20 – 40°C in India and North Africa), while nutrient availability and osmolality in the sand fly gut are changing with the ingested food, obliging parasites to adapt to the changing environment [71]. It would thus be useful to investigate whether polyP also plays a role in adaptation to stresses in the insect vector.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mouse work

All mice studies were approved by the Swiss Federal Veterinary Office (SFVO), under the authorization number 2113. Animal handling and experimental procedures were undertaken with strict adherence to ethical guidelines set out by the SFVO and under inspection by the Department of Security and Environment of the State of Vaud, Switzerland.

–

Parasite strains and clones

Parasites strains used in this study are described in Table S1.

–

VTC4 knockout and complementation in L. major

VTC4 alleles were successively disrupted by hygromycin and puromycin resistance genes respectively [30]. These constructs were based on the pX63 hygromycin vector [72]. The linear targeting regions were gel-purified before transfection. Complemented lines were obtained by homologous recombination into either the VTC4 or the small subunit ribosomal RNA locus [30].

–

Stem-Loop (StL) RNAi constructs for GFP and L. guyanensis M4147 VTC4

GFP-StL (pIR1SAT-GFP65-StL(b) (B4733)) has been described previously [50]. Two different sequences were used to make the stem-loop constructs (StL) with different selection markers (BSD and PAC, respectively) (Fig. S2). StL#1 and StL#2 arise from nucleotides 193 – 788 and 867 – 1963 of the L. guyanensis M4147 VTC4 gene respectively (GenBank accession number: MF572933). StL constructs were generated using Gateway technology. First, StL#1 and StL#2 were amplified with primers P6425/P6426 and P6429/P6430, respectively (Table S2), and cloned into the pCR® 8/GW/TOPO® vector (Invitrogen cat# K2520-02). These constructs were then used separately to transfer to the Leishmania StL destination vectors pIR1BSD-GW and pIR1PAC-GW respectively, using Clonase II to perform the LR recombination reaction (Invitrogen cat#12535-029) as described previously [48].

–

Leishmania culture

L. major promastigotes were grown at 26°C in M199 medium (Invitrogen AG) complemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS, Seromed GmbH), 50 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin (Amimed), 40 mM Hepes (Amimed), 0.6 mg/L biopterin (Sigma) and 5 mg/L hemin (Sigma). All other Leishmania strains were grown at 26°C in freshly prepared Schneider’s insect medium (Sigma) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (PAA), 10 mM Hepes (Amimed), 50 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin (Amimed), 0.6 mg/L biopterin (Sigma) and 5 mg/L hemin (Sigma). L. mexicana axenic amastigote were obtained as previously described [73]. Parasites were cultured in the above described Schneider’s insect medium supplemented with 20% FBS, at pH 5.4, 34°C in 5% CO2.

–

Leishmania major transfection

Logarithmic promastigotes were transfected following the Amaxa short protocol: 8 – 12 µg linear DNA in a volume of 5 µl H2O were used to transfect 2 x 107 parasites. Parasites were centrifuged (3200 rpm, 10 min) and washed in PBS (1x). The cell pellet was resuspended in 100 µl T cell Nucleofection solution of Amaxa human T cell Nucleofactor kit (Lonza) and the corresponding DNA was added. This mixture was then transferred to the amaxa cuvette and electroporated using the Nucleofector® II device, program U-033. Transfected and electroporated WT control parasites were incubated at 26°C in 4 ml complete M199 overnight. After 24 hours in drug-free media the parasites were plated on semisolid media (1% BactoAgar in complete M199) containing the appropriate drug to select clonal lines. Drug concentrations for selections were 100 µg/ml hygromycin, 50 µg/ml puromycin or 25 µg/ml neomycin. Parasite colonies were recovered from the plates after approximately 10 – 15 days and grown in liquid culture media supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics. The second round of homologous recombination was performed twice in two independent experiments, in order to decrease the possibility of second site mutations. To ensure clonal cultures, drug resistant colonies from semi-liquid plates were further subcloned.

–

Leishmania guyanensis transfection

The parasites were grown to mid-logarithmic phase, pelleted at 1300 x g, washed once with cytomix electroporation buffer (120 mM KCl, 0.15 mM CaCl2, 10 mM K2HPO4, 25 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.6, 2 mM EDTA and 5 mM MgCl2) and resuspended in cytomix at a final concentration of 2 × 108 cells/ml. For transfection, 10 μg of SwaI digested DNA was mixed with 500 μl of cells and electroporated twice in a 0.4 cm gap cuvette at 25 microF, 1400 V (3.75 kV/cm), waiting 10 sec in-between zaps. Following electroporation, cells were incubated at 26°C for 24 hours in drug-free media and then plated on semisolid media containing the appropriate drug to select clonal lines. The digested SwaI DNA fragment was integrated into the ribosomal RNA SSU locus. For selections using blasticidin deaminase (BSD gene) and puromycin (PAC gene) markers, parasites were plated on 10 μg/ml blasticidin, 30 μg/ml puromycin, respectively, together with 50 µg/ml nourseothricin for all plates (as the parental line expresses luciferase with SAT marker). Colonies normally appeared after 14 days, at which point they were recovered, grown to stationary phase in 1 ml and passaged with the appropriate drugs. The efficacy of VTC4 knockdown was measured by RT-PCR using the following primers: VTC4: forward: TGCGAGAGAAATACGACCCC, reverse: ACGTCCTGTGGCAGAAAGAG; KMP11: forward: GCCTGGATGAGGAGTTCAACA, reverse: GTGCTCCTTCATCTCGGG (Table S2).

–

Parasite protein extraction

Logarithmic and stationary phase L. major promastigotes were lysed using the following method: parasites were diluted in PBS (1x) buffer containing 1 mM OPA (o-phenanthroline), 100 µM E64 (trans-epoxysuccinyl-L-leucylamido (4-guanidino) – butane), 5 µg/ml Pepstatin A, 10 µg/ml Leupeptin, 10 µg/ml Aprotinin, 1 mM PMSF and lysed by freeze and thaw with 5 successive passages of 2 minutes at 40°C and in liquid nitrogen. Supernatants (soluble proteins) were saved and the pellets (insoluble proteins) resuspended in 100 µl buffer as described above. Both were stored at -80°C. Protein concentration was quantified using a BCA (bicinchoninic acid) protein assay reagent (Pierce Biotechnology) with bovine serum albumine (BSA) as standard.

–

Immunoblotting

8% polyacrylamide sodium dodecyl sulfate gels were used to separate 20 – 30 µg of pellet and supernatant proteins obtained from cell lysates. Proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Whatman) by electroblotting, probed with an affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal anti-cd-LmjVTC4 antibody (1:1000) and a secondary anti-rabbit antibody (1:2500), which was coupled to HRP (Horse Radish Peroxidase – Promega Corp.), and a mouse anti-α-tubulin antibody (clone B5-1-2, Sigma-Aldrich) was used as loading control. Blots were developed by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection (Amersham Biosciences).

–

PolyP column extraction and colorimetric quantification

Unless otherwise stated, column polyP extractions were performed on 6 x 107 logarithmic phase (day 3 post dilution) promastigotes, or in the case of L. major on 1 – 2 x 108 promastigotes. Cells were washed in PBS (1x) and lysed with 50 µl 1 M H2SO4 and 50 µl 4 M NaOH. 100 µl 1 M Tris-Malate buffer (pH 7.4) were added to the lysate in order to stabilize the compounds. After addition of 600 µl binding buffer (Qiagen PCR purification kit), the lysate was transferred to the column (Qiagen PCR purification columns), centrifuged (1 min, 13000 rpm) and washed twice with 750 µl washing buffer of the kit. After an additional step of centrifugation (1 min, 13000 rpm), polyP was eluted with 110 µl elution buffer from the kit and samples were stored at -20°C.

–

For quantification, isolated polyP was degraded by a polyphosphatase (recombinant S. cerevisiae Ppx1, expressed and purified from E. coli) and the released Pi was stained with malachite green. For this, the polyP extract was mixed 1:1 with the master mix (10 mM Tris pH 7, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.4 µg/ml Ppx1) in a 96-well flat bottom microtiter plate and incubated for 90 min at 37°C. For staining, a mix of 86 µl molybdate solution (34.6 mg/ml ammonium molybdate and 1.12% concentrated H2SO4 in H2O) and 64 µl malachite green solution (0.3 mg/ml malachite green and 3.5 mg/ml polyvinyl alcohol in H2O) were added to each sample and incubated for 4 min. For each sample, a negative control without Ppx1 was incubated in parallel to determine the basal Pi level before the reaction. The absorbance was read at 595 nm with a Synergy microplate reader (BioTek). This method was adapted from [61].

–

PolyP precipitation and gel electrophoresis

PolyP was phenol (pH 4.3, Sigma) – chloroform extracted and precipitated in 100% ethanol at -20°C overnight (adapted from [74]). Ethanol was removed and the pellet resuspended in H2O. Different enzymes were added to digest RNA (recombinant RNAse, Roche), DNA (recombinant DNAse I, Roche) and Ppx1 (recombinant S. cerevisiae PPX expressed and purified from E. coli) at 37°C. PolyP was resolved using a 24 x 16 x 0.1-cm gel with 30 – 35% polyacrylamide (Acrylamide/Bis 19:1, SERVA) in Tris-Borate-EDTA buffer. Before loading the samples, gels were pre-run for 60 min at 3 mA. Samples were run at 3 mA overnight at 4°C, until the loading dye (30% glycerol, 0.5% bromophenol blue, 1 mM EDTA in H2O) front migrated to ½ – ¾ of the gel. Gels were stained with DAPI (1.5 g/L Tris base, 2% glycerol, 2 mg/L DAPI) for 45 – 60 min, and destained with the same buffer without DAPI for 30 – 45 min. Gels were exposed to a UV transilluminator for 5 – 20 min to induce photobleaching, after which photographs were taken [75].

–

High temperature stress

Logarithmic growth phase (day 3 post dilution) or stationary phase (day 6 post dilution) promastigotes were centrifuged, washed with minimal media and resuspended in the corresponding media: complete M199 for L. major and complete Schneider’s for L. guyanensis. Parasites were grown in duplicates (in 24-well plates) at 26 or 37°C, and the number of dead cells was assessed at the indicated time points using propidium iodide (PI) staining. 200 µl of propidium iodide diluted in PBS to 5 ml were added to 20 ml of parasite culture and, after 3 – 4 minutes of incubation at room temperature, samples were analyzed by flow cytometry using a BD AccuriTM C6 Cytometer (BD Biosciences).

–

PNA agglutination assay

Agglutination assays were performed with 1 – 2 x 108 late stationary phase (day 6 post dilution) parasites in 1 ml and 50 μg/ml peanut agglutinin (Sigma) [76]. After 30 min incubation at room temperature in DMEM (Gibco), cells were separated by centrifugation: 10 min at 200 x g yielded the cells agglutinated with PNA (PNA+), and 10 min at 1990 x g yielded the free PNA– metacyclic parasites. Both parasite fractions were washed once with 10 ml DMEM supplemented with 20 mM galactose, in order to separate agglomerates. Parasites were then resuspended in DMEM and counted.

–

Ficoll gradient centrifugation

Late stationary phase (day 6 post dilution) parasites were washed, resuspended in 2 ml DMEM and transferred into a glass tube. 2 ml of 10% and 20% ficoll (Sigma F5415) diluted in DMEM were added to the bottom of the tube to form a gradient. After centrifugation at 2500 rpm for 15 min (without brake), the upper 2 phases were collected, without touching the interphase below, and washed. Parasites were resuspended in DMEM and counted [57].

–

Mouse infection

Mice were purchased from Harlan (C57BL/6) or Charles River (BALB/c). At the onset of experiments female mice were around 6 weeks of age and maintained under conventional conditions in an animal facility. Late stationary Leishmania parasites were washed in PBS and 3 x 106 parasites were injected subcutaneously in a volume of 50 µl PBS into the hind footpad of mice. The progression of infection was evaluated by measuring the footpad size with a Vernier caliper and footpad swelling was defined by subtracting the thickness of the uninfected footpad from the infected one.

–

Parasite load during in vivo infection with L. guyanensis M4147 expressing luciferase was analyzed using the In Vivo Imaging System (IVIS Lumina II, Xenogen) at the Cellular Imaging Facility (CIF, University of Lausanne). Mice were injected intra-peritoneally with 150 mg/kg D-luciferin 10 min before imaging and anesthetized with isoflurane during imaging. The photons emitted from mouse footpads during a period of 10 min were quantified using the LivingImage version 3.2 software (Caliper Life Science) [59]. Parasite burden was expressed as total photon flux / 10 min emitted from L. guyanensis infected footpad lesions normalized against the background luminescence of uninfected footpads or the tail.

–

Amastigote isolation from footpads

Mouse footpads were excised in a sterile environment. The skin was removed and the footpad fragmented. After homogenizing the fragments in presence of MEG 1x (5.5 mM Glucose, 0.2 mM EDTA in PBS) using a 7 ml homogenizer, the lysate was centrifuged (400 rpm, 5 min, 4°C) to remove debris. The cell containing supernatant was centrifuged (3000 rpm, 10 min, 4°C) and the pellet treated with 10 ml RCRB (168 mM NH4CL in H2O) for 10 min on ice. Amastigotes were washed twice with MEG 1x, passed through a 40 µm as well as an 8 µm filter and counted.

–

References

- J. Alvar, I.D. Vélez, C. Bern, M. Herrero, P. Desjeux, J. Cano, J. Jannin, M.D. Boer, and . , "Leishmaniasis Worldwide and Global Estimates of Its Incidence", PLoS ONE, vol. 7, pp. e35671, 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0035671

- A. Dostálová, and P. Volf, "Leishmania development in sand flies: parasite-vector interactions overview", Parasites & Vectors, vol. 5, 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-5-276

- A. Kornberg, "Inorganic polyphosphate: a molecule of many functions.", Progress in molecular and subcellular biology, 1999. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10448669

- I. Kulaev, V. Vagabov, and T. Kulakovskaya, "New aspects of inorganic polyphosphate metabolism and function.", Journal of bioscience and bioengineering, 1999. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16232585

- M.R.W. Brown, and A. Kornberg, "The long and short of it - polyphosphate, PPK and bacterial survival.", Trends in biochemical sciences, 2008. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18487048

- M.J. Seufferheld, H.M. Alvarez, and M.E. Farias, "Role of polyphosphates in microbial adaptation to extreme environments.", Applied and environmental microbiology, 2008. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18708516

- N.N. Rao, M.R. Gómez-García, and A. Kornberg, "Inorganic Polyphosphate: Essential for Growth and Survival", Annual Review of Biochemistry, vol. 78, pp. 605-647, 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.083007.093039

- K. Kim, N.N. Rao, C.D. Fraley, and A. Kornberg, "Inorganic polyphosphate is essential for long-term survival and virulence factors in Shigella and Salmonella spp.", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 99, pp. 7675-7680, 2002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.112210499

- A. Kornberg, "Inorganic polyphosphate: toward making a forgotten polymer unforgettable.", Journal of bacteriology, 1995. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7836277

- M. Gray, W. Wholey, N. Wagner, C. Cremers, A. Mueller-Schickert, N. Hock, A. Krieger, E. Smith, R. Bender, J. Bardwell, and U. Jakob, "Polyphosphate Is a Primordial Chaperone", Molecular Cell, vol. 53, pp. 689-699, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2014.01.012

- L. Wang, C.D. Fraley, J. Faridi, A. Kornberg, and R.A. Roth, "Inorganic polyphosphate stimulates mammalian TOR, a kinase involved in the proliferation of mammary cancer cells.", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2003. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12970465

- L. Hernandez-Ruiz, I. González-García, C. Castro, J.A. Brieva, and F.A. Ruiz, "Inorganic polyphosphate and specific induction of apoptosis in human plasma cells.", Haematologica, 2006. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16956816

- H.C. Schröder, L. Kurz, W.E. Müller, and B. Lorenz, "Polyphosphate in bone.", Biochemistry. Biokhimiia, 2000. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10739471

- G. Leyhausen, B. Lorenz, H. Zhu, W. Geurtsen, R. Bohnensack, W.E.G. Müller, and H.C. Schröder, "Inorganic Polyphosphate in Human Osteoblast-like Cells", Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, vol. 13, pp. 803-812, 1998. http://dx.doi.org/10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.5.803

- T. Shiba, D. Nishimura, Y. Kawazoe, Y. Onodera, K. Tsutsumi, R. Nakamura, and M. Ohshiro, "Modulation of Mitogenic Activity of Fibroblast Growth Factors by Inorganic Polyphosphate", Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 278, pp. 26788-26792, 2003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M303468200

- E. Pavlov, R. Aschar-Sobbi, M. Campanella, R.J. Turner, M.R. Gómez-García, and A.Y. Abramov, "Inorganic Polyphosphate and Energy Metabolism in Mammalian Cells", Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 285, pp. 9420-9428, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M109.013011

- J.H. Morrissey, S.H. Choi, and S.A. Smith, "Polyphosphate: an ancient molecule that links platelets, coagulation, and inflammation", Blood, vol. 119, pp. 5972-5979, 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2012-03-306605

- S.A. Smith, S.H. Choi, R. Davis-Harrison, J. Huyck, J. Boettcher, C.M. Rienstra, and J.H. Morrissey, "Polyphosphate exerts differential effects on blood clotting, depending on polymer size", Blood, vol. 116, pp. 4353-4359, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2010-01-266791

- K. Ishige, H. Zhang, and A. Kornberg, "Polyphosphate kinase (PPK2), a potent, polyphosphate-driven generator of GTP", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 99, pp. 16684-16688, 2002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.262655299

- L. Achbergerová, and J. Nahálka, "Polyphosphate - an ancient energy source and active metabolic regulator", Microbial Cell Factories, vol. 10, pp. 63, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1475-2859-10-63

- N. Ogawa, J. DeRisi, and P.O. Brown, "New components of a system for phosphate accumulation and polyphosphate metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae revealed by genomic expression analysis.", Molecular biology of the cell, 2000. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11102525

- F.M. Freimoser, H. Hürlimann, C.A. Jakob, T.P. Werner, and N. Amrhein, "Array", Genome Biology, vol. 7, pp. R109, 2006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/gb-2006-7-11-r109

- M. Hothorn, H. Neumann, E.D. Lenherr, M. Wehner, V. Rybin, P.O. Hassa, A. Uttenweiler, M. Reinhardt, A. Schmidt, J. Seiler, A.G. Ladurner, C. Herrmann, K. Scheffzek, and A. Mayer, "Catalytic core of a membrane-associated eukaryotic polyphosphate polymerase.", Science (New York, N.Y.), 2009. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19390046

- O. Müller, M.J. Bayer, C. Peters, J.S. Andersen, M. Mann, and A. Mayer, "The Vtc proteins in vacuole fusion: coupling NSF activity to V(0) trans-complex formation.", The EMBO journal, 2002. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11823419

- O. Müller, H. Neumann, M.J. Bayer, and A. Mayer, "Role of the Vtc proteins in V-ATPase stability and membrane trafficking.", Journal of cell science, 2003. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12584253

- R. Gerasimaitė, S. Sharma, Y. Desfougères, A. Schmidt, and A. Mayer, "Coupled synthesis and translocation restrains polyphosphate to acidocalcisome-like vacuoles and prevents its toxicity", Journal of Cell Science, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1242/jcs.159772

- R. Gerasimaite, I. Pavlovic, S. Capolicchio, A. Hofer, A. Schmidt, H.J. Jessen, and A. Mayer, "Inositol Pyrophosphate Specificity of the SPX-Dependent Polyphosphate Polymerase VTC", ACS Chemical Biology, vol. 12, pp. 648-653, 2017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/acschembio.7b00026

- Y. Desfougères, R. Gerasimaitė, H.J. Jessen, and A. Mayer, "Vtc5, a Novel Subunit of the Vacuolar Transporter Chaperone Complex, Regulates Polyphosphate Synthesis and Phosphate Homeostasis in Yeast", Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 291, pp. 22262-22275, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M116.746784

- R. Wild, R. Gerasimaite, J. Jung, V. Truffault, I. Pavlovic, A. Schmidt, A. Saiardi, H.J. Jessen, Y. Poirier, M. Hothorn, and A. Mayer, "Control of eukaryotic phosphate homeostasis by inositol polyphosphate sensor domains", Science, vol. 352, pp. 986-990, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.aad9858

- S.H. Klompmaker, K. Kohl, N. Fasel, and A. Mayer, "Magnesium uptake by connecting fluid-phase endocytosis to an intracellular inorganic cation filter", Nature Communications, vol. 8, 2017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-01930-5

- A. Uttenweiler, H. Schwarz, H. Neumann, and A. Mayer, "The Vacuolar Transporter Chaperone (VTC) Complex Is Required for Microautophagy", Molecular Biology of the Cell, vol. 18, pp. 166-175, 2007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1091/mbc.E06-08-0664

- J. Fang, P. Rohloff, K. Miranda, and R. Docampo, "Ablation of a small transmembrane protein of Trypanosoma brucei (TbVTC1) involved in the synthesis of polyphosphate alters acidocalcisome biogenesis and function, and leads to a cytokinesis defect", Biochemical Journal, vol. 407, pp. 161-170, 2007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1042/BJ20070612

- G. Lemercier, B. Espiau, F.A. Ruiz, M. Vieira, S. Luo, T. Baltz, R. Docampo, and N. Bakalara, "A pyrophosphatase regulating polyphosphate metabolism in acidocalcisomes is essential for Trypanosoma brucei virulence in mice.", The Journal of biological chemistry, 2003. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14615483

- B. Moreno, J.A. Urbina, E. Oldfield, B.N. Bailey, C.O. Rodrigues, and R. Docampo, "31P NMR Spectroscopy of Trypanosoma brucei, Trypanosoma cruzi, and Leishmania major", Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 275, pp. 28356-28362, 2000. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M003893200

- R. Docampo, V. Jimenez, N. Lander, Z. Li, and S. Niyogi, "New Insights into Roles of Acidocalcisomes and Contractile Vacuole Complex in Osmoregulation in Protists", International Review of Cell and Molecular Biology, pp. 69-113, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-407695-2.00002-0

- N. Lander, P.N. Ulrich, and R. Docampo, "Trypanosoma brucei Vacuolar Transporter Chaperone 4 (TbVtc4) Is an Acidocalcisome Polyphosphate Kinase Required for in Vivo Infection", Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 288, pp. 34205-34216, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M113.518993

- F.A. Ruiz, C.O. Rodrigues, and R. Docampo, "Rapid Changes in Polyphosphate Content within Acidocalcisomes in Response to Cell Growth, Differentiation, and Environmental Stress inTrypanosoma cruzi", Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 276, pp. 26114-26121, 2001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M102402200

- R. Docampo, and S.N. Moreno, "Acidocalcisomes", Cell Calcium, vol. 50, pp. 113-119, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ceca.2011.05.012

- R. Docampo, W. de Souza, K. Miranda, P. Rohloff, and S.N.J. Moreno, "Acidocalcisomes - conserved from bacteria to man.", Nature reviews. Microbiology, 2005. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15738951

- R. Docampo, V. Jimenez, S. King-Keller, Z. Li, and S.N. Moreno, "The Role of Acidocalcisomes in the Stress Response of Trypanosoma cruzi", Advances in Parasitology, pp. 307-324, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-385863-4.00014-9

- S. Besteiro, D. Tonn, L. Tetley, G.H. Coombs, and J.C. Mottram, "The AP3 adaptor is involved in the transport of membrane proteins to acidocalcisomes of Leishmania", Journal of Cell Science, vol. 121, pp. 561-570, 2008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1242/jcs.022574

- T.C.L. de Jesus, R.R. Tonelli, S.C. Nardelli, L. da Silva Augusto, M.C.M. Motta, W. Girard-Dias, K. Miranda, P. Ulrich, V. Jimenez, A. Barquilla, M. Navarro, R. Docampo, and S. Schenkman, "Target of Rapamycin (TOR)-like 1 Kinase Is Involved in the Control of Polyphosphate Levels and Acidocalcisome Maintenance in Trypanosoma brucei", Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 285, pp. 24131-24140, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M110.120212

-

M. Galizzi, J.M. Bustamante, J. Fang, K. Miranda, L.C. Soares Medeiros, R.L. Tarleton, and R. Docampo, "Evidence for the role of vacuolar soluble pyrophosphatase and inorganic polyphosphate in

T rypanosoma cruzi persistence", Molecular Microbiology, vol. 90, pp. 699-715, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/mmi.12392 - L. Madeira da Silva, and S.M. Beverley, "Expansion of the target of rapamycin (TOR) kinase family and function in Leishmania shows that TOR3 is required for acidocalcisome biogenesis and animal infectivity", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 107, pp. 11965-11970, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1004599107

- C.O. Rodrigues, F.A. Ruiz, M. Vieira, J.E. Hill, and R. Docampo, "An Acidocalcisomal Exopolyphosphatase from Leishmania major with High Affinity for Short Chain Polyphosphate", Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 277, pp. 50899-50906, 2002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M208940200

- S.F. Altschul, and W. Gish, "Local alignment statistics.", Methods in enzymology, 1996. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8743700

- A.M. Waterhouse, J.B. Procter, D.M.A. Martin, M. Clamp, and G.J. Barton, "Jalview Version 2—a multiple sequence alignment editor and analysis workbench", Bioinformatics, vol. 25, pp. 1189-1191, 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp033

- L. Lye, K. Owens, H. Shi, S.M.F. Murta, A.C. Vieira, S.J. Turco, C. Tschudi, E. Ullu, and S.M. Beverley, "Retention and Loss of RNA Interference Pathways in Trypanosomatid Protozoans", PLoS Pathogens, vol. 6, pp. e1001161, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1001161

- C.S. Peacock, K. Seeger, D. Harris, L. Murphy, J.C. Ruiz, M.A. Quail, N. Peters, E. Adlem, A. Tivey, M. Aslett, A. Kerhornou, A. Ivens, A. Fraser, M. Rajandream, T. Carver, H. Norbertczak, T. Chillingworth, Z. Hance, K. Jagels, S. Moule, D. Ormond, S. Rutter, R. Squares, S. Whitehead, E. Rabbinowitsch, C. Arrowsmith, B. White, S. Thurston, F. Bringaud, S.L. Baldauf, A. Faulconbridge, D. Jeffares, D.P. Depledge, S.O. Oyola, J.D. Hilley, L.O. Brito, L.R.O. Tosi, B. Barrell, A.K. Cruz, J.C. Mottram, D.F. Smith, and M. Berriman, "Comparative genomic analysis of three Leishmania species that cause diverse human disease", Nature Genetics, vol. 39, pp. 839-847, 2007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ng2053

- K.A. Robinson, and S.M. Beverley, "Improvements in transfection efficiency and tests of RNA interference (RNAi) approaches in the protozoan parasite Leishmania.", Molecular and biochemical parasitology, 2003. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12742588

-

V.D. Atayde, H. Shi, J.B. Franklin, N. Carriero, T. Notton, L. Lye, K. Owens, S.M. Beverley, C. Tschudi, and E. Ullu, "The structure and repertoire of small interfering

RNAs inL eishmania (V iannia) braziliensis reveal diversification in the trypanosomatidRNAi pathway", Molecular Microbiology, vol. 87, pp. 580-593, 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/mmi.12117 - P.J. Rooney, L. Ayong, C.M. Tobin, S.N. Moreno, and L.J. Knoll, "TgVTC2 is involved in polyphosphate accumulation in Toxoplasma gondii", Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology, vol. 176, pp. 121-126, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molbiopara.2010.12.012

- P.N. Ulrich, N. Lander, S.P. Kurup, L. Reiss, J. Brewer, L.C. Soares Medeiros, K. Miranda, and R. Docampo, "The Acidocalcisome Vacuolar Transporter Chaperone 4 Catalyzes the Synthesis of Polyphosphate in Insect‐stages of Trypanosoma brucei and T. cruzi", Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology, vol. 61, pp. 155-165, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jeu.12093

- M.J. McConville, S.J. Turco, M.A. Ferguson, and D.L. Sacks, "Developmental modification of lipophosphoglycan during the differentiation of Leishmania major promastigotes to an infectious stage.", The EMBO journal, 1992. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1396559

- S.J. Turco, and A. Descoteaux, "THE LIPOPHOSPHOGLYCAN OF LEISHMANIA PARASITES", Annual Review of Microbiology, vol. 46, pp. 65-92, 1992. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.mi.46.100192.000433

- D.L. Sacks, "Leishmania-sand fly interactions controlling species-specific vector competence.", Cellular microbiology, 2001. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11298643

- G.F. Späth, and S.M. Beverley, "A Lipophosphoglycan-Independent Method for Isolation of Infective Leishmania Metacyclic Promastigotes by Density Gradient Centrifugation", Experimental Parasitology, vol. 99, pp. 97-103, 2001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/expr.2001.4656

- J.J. Blum, "Changes in orthophosphate, pyrophosphate and long-chain polyphosphate levels in Leishmania major promastigotes incubated with and without glucose.", The Journal of protozoology, 1989. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2543817

- A. Ives, C. Ronet, F. Prevel, G. Ruzzante, S. Fuertes-Marraco, F. Schutz, H. Zangger, M. Revaz-Breton, L. Lye, S.M. Hickerson, S.M. Beverley, H. Acha-Orbea, P. Launois, N. Fasel, and S. Masina, "Leishmania RNA Virus Controls the Severity of Mucocutaneous Leishmaniasis", Science, vol. 331, pp. 775-778, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1199326

- N.N. Rao, S. Liu, and A. Kornberg, "Inorganic polyphosphate in Escherichia coli: the phosphate regulon and the stringent response.", Journal of bacteriology, 1998. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9555903

- T.P. Werner, N. Amrhein, and F.M. Freimoser, "Novel method for the quantification of inorganic polyphosphate (iPoP) in Saccharomyces cerevisiae shows dependence of iPoP content on the growth phase", Archives of Microbiology, vol. 184, pp. 129-136, 2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00203-005-0031-2

- J. Fang, F.A. Ruiz, M. Docampo, S. Luo, J.C.F. Rodrigues, L.S. Motta, P. Rohloff, and R. Docampo, "Overexpression of a Zn2+-sensitive soluble exopolyphosphatase from Trypanosoma cruzi depletes polyphosphate and affects osmoregulation.", The Journal of biological chemistry, 2007. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17827150

- G. Huang, J. Fang, C. Sant'Anna, Z. Li, D.L. Wellems, P. Rohloff, and R. Docampo, "Adaptor Protein-3 (AP-3) Complex Mediates the Biogenesis of Acidocalcisomes and Is Essential for Growth and Virulence of Trypanosoma brucei", Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 286, pp. 36619-36630, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M111.284661

- D. Sarkar, and A. Bhaduri, "Temperature-induced rapid increase in cytoplasmic free Ca2+ in pathogenic Leishmania donovani promastigotes.", FEBS letters, 1995. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7498487

- T. Naderer, O. Dandash, and M.J. McConville, "Calcineurin is required for Leishmania major stress response pathways and for virulence in the mammalian host", Molecular Microbiology, vol. 80, pp. 471-480, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07584.x

- G. Huang, P.J. Bartlett, A.P. Thomas, S.N.J. Moreno, and R. Docampo, "Acidocalcisomes of Trypanosoma brucei have an inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor that is required for growth and infectivity", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 110, pp. 1887-1892, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1216955110

- F. Garcia-del Portillo, J.W. Foster, M.E. Maguire, and B.B. Finlay, "Characterization of the micro-environment of Salmonella typhimurium-containing vacuoles within MDCK epithelial cells.", Molecular microbiology, 1992. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1484485

- F.M. Mann, B.C. VanderVen, and R.J. Peters, "Magnesium depletion triggers production of an immune modulating diterpenoid in Mycobacterium tuberculosis", Molecular Microbiology, vol. 79, pp. 1594-1601, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07545.x

- S. Eriksson, S. Lucchini, A. Thompson, M. Rhen, and J.C.D. Hinton, "Unravelling the biology of macrophage infection by gene expression profiling of intracellular Salmonella enterica.", Molecular microbiology, 2003. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12492857

- H. Lanza, S.R. Afonso-Cardoso, A.G. Silva, D.R. Napolitano, F.S. Espíndola, J.D.O. Pena, and M.A. Souza, "Comparative effect of ion calcium and magnesium in the activation and infection of the murine macrophage by Leishmania major.", Biological research, 2004. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15515964

- A. LEFURGEY, M. GANNON, J. BLUM, and P. INGRAM, "Leishmania donovani Amastigotes Mobilize Organic and Inorganic Osmolytes During Regulatory Volume Decrease", Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology, vol. 52, pp. 277-289, 2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1550-7408.2005.00030.x

- A. Cruz, C.M. Coburn, and S.M. Beverley, "Double targeted gene replacement for creating null mutants.", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 1991. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1651496

- P.A. Bates, "Complete developmental cycle of Leishmania mexicana in axenic culture.", Parasitology, 1994. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8152848

- A. Lonetti, Z. Szijgyarto, D. Bosch, O. Loss, C. Azevedo, and A. Saiardi, "Identification of an Evolutionarily Conserved Family of Inorganic Polyphosphate Endopolyphosphatases", Journal of Biological Chemistry, vol. 286, pp. 31966-31974, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M111.266320

- S.A. Smith, and J.H. Morrissey, "Sensitive fluorescence detection of polyphosphate in polyacrylamide gels using 4′,6‐diamidino‐2‐phenylindol", ELECTROPHORESIS, vol. 28, pp. 3461-3465, 2007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/Elps.200700041

- R. da Silva, and D.L. Sacks, "Metacyclogenesis is a major determinant of Leishmania promastigote virulence and attenuation.", Infection and immunity, 1987. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3666964

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

![]() Download Supplemental Information

Download Supplemental Information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the C.R.B. in Montpellier for providing us several Leishmania strains. We thank Slavica Masina and Filipa Daniela Pinheiro Teixeira for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was funded by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation (FNRS 310030-153204; FNRS 310030-173180 and IZRJZ3_164176) (NF) and CRS115_170925 (AM), the Institute for Rheumatology Research (IRR), the COST action CM 0801 and CM1307 SEFRI: C14.0070 (NF and AM). SMB, KLO and LFL were supported by the NIH (AI R01-29646).

COPYRIGHT

© 2018

Importance of polyphosphate in the Leishmania life cycle by Kohl et al. is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.